Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Mental Disorders Due to a General Medical Condition

Pseudobulbar Palsy

Pseudobulbar Palsy

Definition

When fully developed, this syndrome is

characterized by emo-tional incontinence (also known as ãpathological laughing

and cryingã), dysarthria, dysphagia, a brisk jaw-jerk and gag reflex, and

difficulty in protruding the tongue.

The most remarkable aspect of the syndrome is the emotional incontinence. Here, patients experience uncontrol-lable paroxysms of laughter or crying, often in response to minor stimuli, such as the approach of the physician to the bedside (Lieberman and Benson, 1977). Importantly, despite the strength of these outbursts, patients do not experience any corresponding sense of mirth or sadness; some may attempt to stop the emotional display, only to become acutely distressed at their inability to do so: one patient, who experienced ãgales of laughterã whenever he attempted to speak, ãfelt foolish and ashamed, and had tears in his eyes because he could not ãcon-trol the laughterã ã (Davison and Kelman, 1939). Some may go out of their way to avoid having these paroxysms. In one case, described by Wilson (1924), the patient ãused to walk about the hospital with his eyes glued to the ground (because) if he so much as raised them to meet anyone elseãs gaze he was im-mediately overcome by compulsory laughter, which sometimes lasted for 4 or 5 minutesã.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

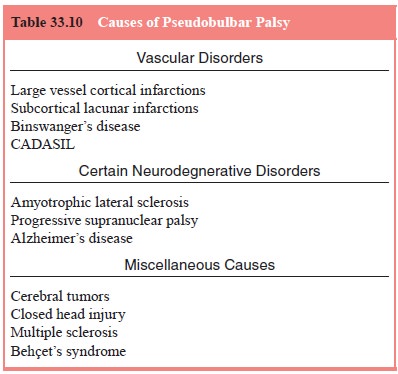

Pseudobulbar palsy results from bilateral

interruption of corti-cobulbar fibers, with this interruption occurring

anywhere from the cortex through the centrum semiovale to the internal capsule

and down to the midbrain and pons. Thus ãreleasedã from upper motor neuron

control, the bulbar nuclei act reflexively, creating, in a sense, a kind of

ãspasticityã of emotional display. The vari-ous disorders capable of causing

such a bilateral interruption are listed in Table 33.10.

Vascular

disorders are by far the most common cause of

bilateral interruption of the corticobulbar tracts, as may be seen with

infarctions of the cortex or with lacunar infarctions in the corona radiata or

internal capsule. Although in some cases it appears that the syndrome occurs

after only one stroke, further investigation typically reveals evidence of a

preexisting lesion on the contralateral side, a lesion which had been

clinically ãsi-lentã (Besson et al.,

1991). Other vascular causes include Bin-swangerãs disease, characterized by diffuse

white matter damage in the centrum semiovale, and CADASIL (Cerebral Autosomal

Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoen-cephalopathy),

characterized by both subcortical infarctions and a widespread

leukoencephalopathy.

Of the neurodegenerative

disorders associated with pseudobulbar palsy, the most prominent is

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, wherein approximately one-half of patients are

eventu-ally so affected (Gallagher, 1989).

Of the miscellaneous

causes, cerebral tumors which bilaterally compress or invade the brainstem

are particularly important

Assessment and Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis should be suspected whenever patients

present with exaggerated and uncontrollable emotional displays. Labil-ity of

affect, as may be seen in mania, is ruled out by the fact that the labile

patient, while displaying the affect, also experiences a congruent emotional

feeling: by contrast, in emotional incon-tinence the patient often feels

nothing, except perhaps conster-nation at the unmotivated and uncontrollable

emotional display. Inappropriate affect, as may be seen in schizophrenia, is

similar to emotional incontinence in that patients with schizophrenia may not

experience any corresponding feeling: in schizophre-nia, however, one sees

other accompanying symptoms, such as mannerisms, hallucinations and delusions,

symptoms which are absent in pseudobulbar palsy. ãEmotionalismã, as may be seen

after strokes, may suggest the diagnosis, especially given the clinical

setting, however here, as with lability, patients also experience a concurrent

feeling that is congruent with the emo-tional display.

Findings on the neurologic examination are also

helpful. Bilateral interruption of corticobulbar tracts, as noted above,

typically leads to cranial nerve dysfunction with dysarthria, dys-phagia and

brisk jaw-jerk and gag reflexes. Given the proximity of the corticospinal

tracts, one often also finds evidence of long-tract damage, such as hemiplegia

or Babinski signs.

MRI scanning is generally diagnostic in cases

secondary to vascular lesions, tumors and multiple sclerosis. Amyotrophic

lateral sclerosis is suggested by the gradual progression of upper and lower

motor neuron signs and symptoms; progressive supra-nuclear palsy by the

presence of parkinsonism and supranuclear gaze palsy, and Alzheimerãs disease

by the long history of a grad-ually progressive dementia.

Epidemiology and Comorbidity

Pseudobulbar palsy is not uncommon: as noted above,

it is found in almost half of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. It

may also be seen in a much smaller, but still clinically significant,

proportion of patients with vascular lesions, Alzheimerãs disease and multiple

sclerosis.

Course

The overall course of the syndrome reflects the

course of the etio-logic disorder. The appearance of dysphagia, however, is an

omi-nous sign, carrying, as it does, the risk of aspiration.

Treatment

In addition to treating, if possible, the

underlying cause, various medications may be used to reduce the severity of the

emotional incontinence, including tricyclics and SSRIs. Among the tricy-clics,

both amitriptyline (in doses of 50ã75 mg) and nortriptyline (in doses up to 100

mg) are effective, with nortriptyline generally better tolerated. Of the SSRIs,

citalopram, in a dose of 20 mg, was effective, and there are also case reports

of the effectiveness of paroxetine, sertraline and fluoxetine (Seliger and

Hornstein, 1989). Overall, it is probably best to begin with an SSRI, and to

hold nortriptyline in reserve.

Related Topics