Chapter: Pharmaceutical Biotechnology: Fundamentals and Applications : Gene Therapy

Production and Processing of Non-Viral Vectors

Production and Processing of Non-Viral Vectors

One benefit of non-viral vectors for gene transfer is that the production process is rather generic and can be applied to any plasmid preparation regardless of composition or application. Since the current average human dose of plasmid DNA for gene transfer and vaccination is approximately one milligram (Manthorpe, 2005), the primary challenge associated with large-scale production of plasmids is to develop a process that is both scalable and economical. Thus, process development for plasmid-based gene transfer remains an active area of research and development (Schorr, 2006). A standard process for large-scale production of recombinant DNA plasmids consists of five unit operations.

Fermentation

Fermentation processes must support growth of transformed bacteria and maximize the amount of plasmid produced by each cell. Escherichia coli is the most common strain used for plasmid production. Amino acids, nucleosides and the ratio of nitrogen to carbon containing compounds present in a rich media formulation greatly improve plasmid yield (O’Kennedy, 2000).

Harvest

Bacterial cells are either harvested by centrifugation or microfiltration. Centrifugation under Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) conditions can be costly, making microfiltration the accepted method of cell harvest (Manthorpe, 2005). This also allows for spent media, metabolic byproducts, extracellular debris and impurities to be washed away prior to purification.

Lysis

Bacterial cells must be lysed to release the recombi-nant plasmids. This is one of the most critical steps in the production process since it can significantly affect the amount of usable (covalently closed circular, ccc) and unusable (sheared, partially denatured and open circular) forms of DNA in a preparation. The most widely used method of lysis for clinical-scale manu-facturing is treatment with alkaline detergent and precipitation of cellular debris with acetate (Shamlou, 2003). This removes a significant fraction of cellular impurities from the lysate, but increases thesensitivity of plasmids to mixing and localized concentrations of detergent, which are hard to manipulate on a large scale. Lysis of cells through heat exposure addresses this issue and effectively denatures cellular proteins and bacterial DNA.

Isolation/Purification

Some processes include additional steps for removal of cellular debris and other contaminants from crude bacterial lysates such as precipitation with detergents, polyethylene glycol or salt (Birnboim, 1979; Nicoletti, 1993; Murphy, 2006). These reagents affect plasmid stability and are removed by column chromatography. Size exclusion chromatography can effectively sepa-rate plasmid DNA from RNA, proteins and other small molecules present in the cleared lysate. The degree of separation of plasmid DNA from contami-nants is highly dependent upon the type and concentration of salt in the running buffer. Resins used in anion exchange chromatography have a high affinity for plasmid DNA and provide maximal sample concentration (Shamlou, 2003; Stadler, 2004; Schorr, 2006). Hydrophobic interaction and thiophilic aromatic chromatography are the methods of choice for selective separation of the different plasmid DNA isoforms and endotoxin reduction.

Bulk Preparation

After purification, the bulk plasmid is placed in a suitable buffer and formulation by ultrafiltration using a membrane with a pore size of 50 to 100 kDa.

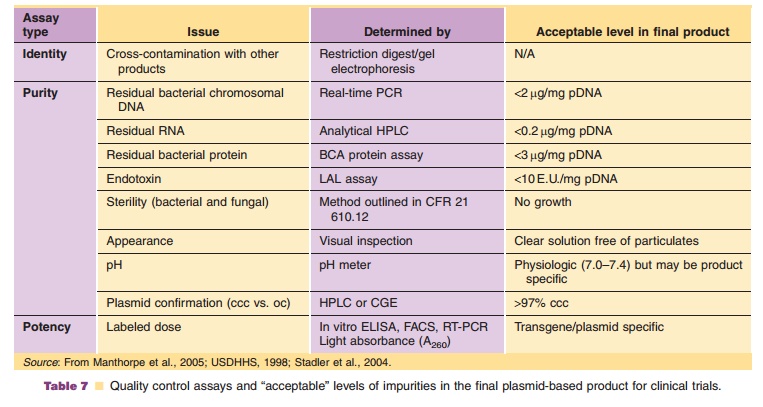

Plasmids for clinical use must be highly char-acterized. Impurities from production and processing steps are well known. Tests necessary to confirm the identity, purity and potency of a plasmid-based product are well-established and routine. These tests and the current specifications set by the FDA and the World Health Organization are summarized in Table 7.

Related Topics