Chapter: Paediatrics: Neonatology

Paediatrics: Acute respiratory diseases

Acute respiratory diseases

All of the diseases presented

below have signs of respiratory distress. Cerebral hypoxia, congenital heart

disease, and metabolic aci-dosis can induce respiratory distress (suspect if

CXR is normal).

Transient tachypnoea of the newborn (TTN)

ŌĆó

Caused

by delayed clearance/absorption of lung fluid after birth.

ŌĆó

Presents

within 4hr after birth. Common after elective CS. CXR: shows streaky perihilar

changes and fluid in lung horizontal fissures.

ŌĆó

Treatment:

supplemental O2. Consider nasal CPAP and antibiotics.

ŌĆó

Spontaneously

resolves within 24hr.

Congenital pneumonia

ŌĆó

Caused

by aspiration of infected amniotic fluid.

ŌĆó

Associated

with prolonged rupture of membranes (PROM), chorioamnionitis, foetal hypoxia.

ŌĆó

Usually

group B streptococci, Escherichia coli,

other Gram ŌĆōve bacteria, listeria, chlamydia.

ŌĆó

Presents

in first 24hr. CXR: patchy shadowing and consolidation.

ŌĆó

Respiratory support: antibiotics (benzylpenicillin, or

ampicillin if listeria, and

gentamicin) after septic screen; chest physiotherapy.

ŌĆó

Prognosis: depends on severity and associated

sepsis or persistent pulmonary

hypertension of newborn (PPHN).

Meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS) (1ŌĆō5/1000 live births)

ŌĆó

5% of

term infants with meconium-stained liquor develop MAS.

ŌĆó

Hypoxia

results in gasping and meconium passage in

utero, a combination that leads to aspiration. Meconium aspiration inhibits

surfactant, obstructs the respiratory tract, and induces pneumonitis.

ŌĆó

Presents

with respiratory distress soon after birth. Associated with pulmonary air leaks

and PPHN. CXR: generalized lung over inflation with patchy

collapse/consolidation +/ŌĆō air leaks.

ŌĆó

Prevention: if liquor is meconium-stained,

delivery should be expedited to

prevent further hypoxia and gasping. If baby is apnoeic at birth, visualize the

larynx and suck out any meconium from larynx/trachea. Tracheal suction is not

recommended for vigorous infants.

ŌĆó

Treatment: supplemental O2;

intermittent positive pressure ventilation

(IPPV) or high frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) if ventilation

required; surfactant; antibiotics (since listeria can cause antenatal meconium

passage); treat any PPHN; consider ECMO if severe.

ŌĆó

Prognosis: mortality <5%. Survivors do

well, but there is ŌĆśriseŌĆÖrisk of asthma and, if extracorporeal membrane

oxygenation (ECMO) is needed, neurological sequelae.

Pulmonary air leaks

Commonly secondary to other

respiratory disease (e.g. RDS, MAS) or to assisted ventilation.

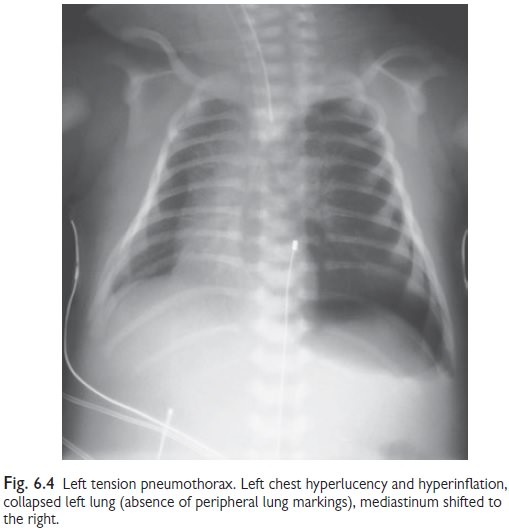

Pneumothorax

Spontaneous pneumothorax occurs in

72% term infants. Incidence is increased in prematurity and respiratory

disease.

ŌĆó

Features: majority are small, asymptomatic,

and resolve spontaneously. If large,

present with respiratory distress. Tension pneumothorax is life-threatening

(signs: respiratory distress, cyanosis, mediastinal shift away from affected

side, ŌĆśfallŌĆÖ chest movement and air entry on affected side, transillumination

lights up affected side).

ŌĆó

CXR: shows ipsilateral translucency,

lack of peripheral lung markings, collapsed

lung (see Fig. 6.4).

ŌĆó

Treatment: none if asymptomatic. Give O2 as required. If symptoms are severe or worsening, insert chest

drain. In emergency, perform needle aspiration before chest drain.

ŌĆó

Prognosis: excellent in term infants.

Mortality is doubled in infants with RDS.

Also ŌĆśriseŌĆÖrisk of periventricular haemorrhage in preterms.

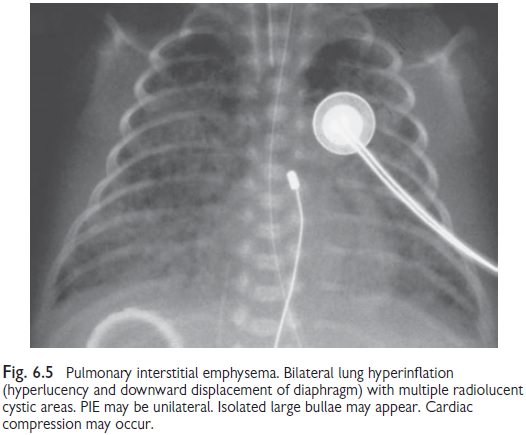

Pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE)

Air leak into lung parenchyma

results in small airway and alveolar col-lapse. Follows high IPPV, particularly

in preterm infants with severe RDS or MAS.

ŌĆó Signs:

respiratory distress; chest

hyperexpansion; poor air entry; coarse inspiratory

crackles.

ŌĆó CXR:

hyperinflation; ŌĆśhoneycombŌĆÖ

pattern of cystic lucencies/bullae,

generalized or local (see Fig. 6.5).

ŌĆó Treatment:

high FiO2, low PIP, low

PEEP, fast rate IPPV; HFOV may be

ŌĆó

superior.

Unilateral PIE: nurse infant with affected side down. In refractory cases

consider selective intubation to ventilate the healthier lung.

ŌĆó Prognosis:

mortality 25ŌĆō50%. There is an

increased risk of bronchopulmonary

dysplasia.

Pneumomediastinum

Often preceded by asymptomatic

pneumothorax/PIE.

ŌĆó

CXR: translucency around the heart

extending superiorly; thymus lifted and

splayed from below (ŌĆśsailŌĆÖ sign).

ŌĆó

Treatment: usually no treatment is required.

Pneumopericardium

Usually occurs with other air

leaks associated with IPPV and can

lead to cardiac tamponade (with quiet heart sounds, hypo-tension, bradycardia,

cyanosis).

ŌĆó

CXR: translucency around the borders of

a small heart.

ŌĆó

Treatment: urgent needle drainage inserted

under the xiphisternum.

ŌĆó

Prognosis: high mortality if symptomatic.

Pneumoperitoneum

Air can occasionally track into

the peritoneum from a pulmonary air

leak. AXR confirms the diagnosis. Severe abdominal disten-tion could impair

ventilation. Drain if symptomatic.

Massive pulmonary haemorrhage (1/1000 live births)

Usually due to haemorrhagic

pulmonary oedema in VLBW infants. Small bleeds are associated with tracheal

trauma from ETT or suction. It is associated with: PDA, heart failure, PIE,

hydrops foetalis, perinatal hypoxia, sepsis, coagulopathy, fluid overload,

surfactant therapy

Signs

ŌĆó

Rapid

systemic collapse.

ŌĆó

Profuse

bloodstained fluid welling up from upper airway.

ŌĆó

Respiratory

crackles on auscultation.

ŌĆó

CXR. Virtual

ŌĆśwhite outŌĆÖ. Consider echocardiography to detect PDA.

Treatment

ŌĆó

rise O2

and ventilatory pressures.

ŌĆó

Frequent

endotracheal suction.

ŌĆó

Correct

hypovolaemia and coagulopathy.

ŌĆó

Consider

blood transfusion.

ŌĆó

Consider

surfactant.

ŌĆó

Treat

known associations.

Milk aspiration

Term infants can accidentally

aspirate a feed. The usual causes are:

ŌĆó

Swallowing

incoordination, e.g. preterm, neurological disease.

ŌĆó

Upper

airway or oesophageal disorders, e.g. tracheo-oesophageal fistula,

gastro-oesophageal reflux.

Presentation

Sudden choking or respiratory

distress during or after a feed, often with excessive milk in the mouth, or

aspiration pneumonia.

CXR:

normal or patchy

collapse/consolidation in the upper lobes.

Treatment

If well, observe only. If unwell, respiratory

support and broad spectrum

antibiotics are needed. Investigate cause and use gastric or naso-jejunal tube

feeding. Period of IV fluids or feeding may be necessary.

Apnoea

Apnoea can result from any severe

illness.

Management

ŌĆó

Support

respiration.

ŌĆó

Investigate

and correct primary cause.

Apnoea of prematurity

ŌĆó

Common

below 34wks gestation (incidence ŌĆśriseŌĆÖas gestation d).

ŌĆó

Between

episodes the infant is well.

ŌĆó

Consider

and exclude other diagnoses.

Treatment

Tactile stimulation, blood transfusion,

continuous tube gastric feeds,

caffeine or theophylline, nasal CPAP, or IPPV.

Prognosis

Short-lived apnoeas appear to

cause no harm and should resolve by

34wks gestation.

Related Topics