Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Perioperative & Critical Care Medicine: Anesthetic Complications

Occupational Hazards in Anesthesiology

OCCUPATIONAL HAZARDS IN ANESTHESIOLOGY

Anesthesiologists spend much of their workday exposed to anesthetic

gases, low-dose ionizing radiation, electromagnetic fields, blood products,

and workplace stress. Each of these can

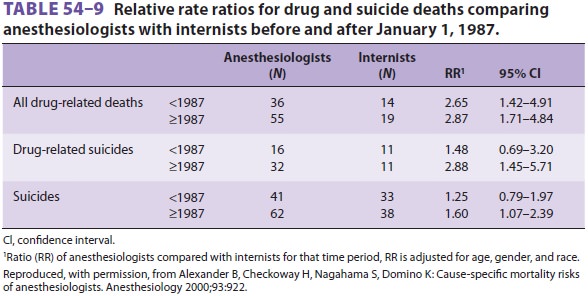

contribute to negative health effects in anesthesia practitio-ners. A 2000

paper compared the mortality risks of anesthesiologists and internists. Death

from heart disease or cancer did not differ between the groups; however,

anesthesiologists had an increased rate of suicides and drug-related deaths (Table

54–9). Anesthesiologists also had a greater

chance of death from external causes, such as boating, bicycling, and

aeronautical accidents compared with internists. Nevertheless, both

anesthesiologists and internists had lower mortality than the general

population, likely due to their higher socioeconomic status. Anesthesiologists’

access to intravenous opioids likely contributes to a 2.21 relative risk for

drug-related deaths compared with that of internists.

1. Chronic Exposure to Anesthetic Gases

There is no clear evidence that exposure to

trace amounts of anesthetic agents presents ahealth hazard to operating room

personnel. How-ever, because previous studies examining this issue have yielded

flawed but conflicting results, the US Occupational Health and Safety

Administration continues to set maximum acceptable trace concen-trations of

less than 25 ppm for nitrous oxide and 0.5 ppm for halogenated anesthetics (2

ppm if the halogenated agent is used alone). Achieving these low levels depends

on efficient scavenging equip-ment, adequate operating room ventilation, and

conscientious anesthetic technique. Most people cannot detect the odor of

volatile agents at a concen-tration of less than 30 ppm. If there is no

functioning scavenging system, anesthetic gas concentrations reach 3000 ppm for

nitrous oxide and 50 ppm for volatile agents.

Early studies indicated that female operating room staff might be at

increased risk of spontaneous abortion compared with other women. It is unclear

if other factors related to operating room activ-ity could also contribute to

the possibly increased potential for pregnancy loss.

2. Infectious Diseases

Hospital workers are exposed to many

infectious diseases prevalent in the community (eg, respiratory viral

infections, rubella, and tuberculosis).

Herpetic whitlow is an infection of the

finger with herpes simplex virus type 1 or 2 and usually involves direct

contact of previously traumatized skin with contaminated oral secretions.

Painful ves-icles appear at the site of infection. The diagnosis is confirmed

by the appearance of giant epithelial cells or nuclear inclusion bodies in a

smear taken from the base of a vesicle, the presence of a rise in herpes

simplex virus titer, or identification of the virus with antiserum. Treatment

is conservative and includes topical application of 5% acyclovir ointment.

Pre-vention involves wearing gloves when contacting oral secretions. Patients

at risk of harboring the virus include those suffering from other infections,

immunosuppression, cancer, and malnutrition. The risk of this condition has

virtually disappeared now that anesthesia personnel routinely wear gloves

dur-ing manipulation of the airway, which was not the case in the 1980s and

earlier.

Viral DNA has been identified in the smoke plume generated during laser

treatment of condy-lomata. The theoretical possibility of viral transmis-sion

from this source can be minimized by using smoke evacuators, gloves, and

appropriate OSHA approved masks.

More disturbing is the potential of acquiring

serious blood-borne infections, such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Although parenteral transmission of these

diseases can occur following mucous membrane, cutaneous, or percutaneous

exposure to infected body fluids, accidental injury with a needle contami-nated

with infected blood represents the most com-mon occupational mechanism. The

risk of transmission can be estimated if three factors are known: the

prevalence of the infection within the patient population, the incidence of

exposure (eg, frequency of needlestick), and the rate of serocon-version after

a single exposure. The seroconversion rate after a specific exposure depends on

several fac-tors, including the infectivity of the organism, the stage of the

patient’s disease (extent of viremia), the size of the inoculum, and the immune

status of the healthcare provider. Rates of seroconversion fol-lowing a single

needlestick are estimated to rangebetween 0.3% and 30%. Hollow (hypodermic)

needles pose a greater risk than do solid (surgical) needles because of the

potentially larger inoc-ulum. The use of gloves, needleless systems, or

protected needle devices may decrease the incidence of some (but not all) types

of injury.

The initial management of needlesticks involves cleaning the wound and

notifying the appropriate authority within the health care facil-ity. After an

exposure, anesthesia workers should report to their institution’s emergency or

employee health department for appropriate counseling on postexposure

prophylaxis options. All OR staff should be made aware of the institution’s

employee health notification pathway for needle stick and other injuries

Fulminant hepatitis B (1% of acute

infections) carries a 60% mortality rate. Chronic active hepati-tis (<5% of all cases) is

associated with an increased incidence of cirrhosis of the liver and hepatocellu-lar

carcinoma. Transmission of the virus is primar-ily through contact with blood

products or body fluids. The diagnosis is confirmed by detection of hepatitis B

surface antigen (HBsAg). Uncompli-cated recovery is signaled by the

disappearance of HBsAg and the appearance of antibody to the surface antigen

(anti-HBs). A hepatitis B vaccine is available and is strongly recommended

prophylac-tically for anesthesia personnel. The appearance of anti-HBs after a

three-dose regimen indicates suc-cessful immunization.

Hepatitis C is another important occupational hazard in anesthesiology;

4% to 8% of hepatitis C infections occur in healthcare workers. Most (50% to

90%) of these infections lead to chronic hepatitis, which, although often

asymptomatic, can progress to liver failure and death. In fact, hepatitis C is

the most common cause of nonalcoholic cirrhosis in the United States. There is

currently no vaccine to pro-tect against hepatitis C infection.

Anesthesia personnel seem to be at a low, but

measureable, risk for the occupational contraction of HIV. The risk of

acquiring HIV infection follow-ing a single needlestick contaminated with blood

from an HIV-infected patient has been estimated at 0.4% to 0.5%. Because there

are documented reports of transmission of HIV from infected patients to

healthcare workers (including anesthesiologists), the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention proposed guidelines that apply to all categories of

patient contact. These universal precautions, which are equally valid for protection

against hepatitis B orinfection, are as follows:

·

No recapping and the immediate

disposal of contaminated needles

·

Use of gloves and other barriers

during contact with open wounds and body fluids

·

Frequent hand washing

·

Use of proper techniques for

disinfection or the disposal of contaminated materials

·

Particular caution by pregnant

healthcare workers, and no contact with patients by workers who have exudative

or weeping skin lesions

3. Substance Abuse

Anesthesiology is a high-risk medical spe-cialty

for substance abuse. Probable reasonsfor this include the stress of anesthetic

practice and the easy availability of drugs with addiction poten-tial

(potentially attracting people at risk of addiction to the field). The

likelihood of developing substance abuse is increased by coexisting personal

problems (eg, marital or financial difficulties) or a family his-tory of

alcoholism or drug addiction.

The voluntary use of nonprescribed

mood-altering pharmaceuticals is a disease. If left untreated, substance abuse

often leads to death from drug overdose—intentional or unintentional. One of

the greatest challenges in treating drug abuse is identify-ing the afflicted

individual, as denial is a consistent feature. Unfortunately, changes evident

to an out-side observer are often both vague and late: reduced involvement in

social activities, subtle changes in appearance, extreme mood swings, and

altered work habits. Treatment begins with a careful, well-planned

intervention. Those inexperienced in this area would be well advised to consult

with their local medical society or licensing authority about how to proceed.

The goal is to enroll the individual in a formal reha-bilitation program. The

possibility that one may lose one’s medical license and be unable to return to

practice provides powerful motivation. Some diver-sion programs report a

success rate of approximately 70%; however, most rehabilitation programs

reportrecurrence rate of at least 25%. Long-term compli-ance often involves

continued participation in sup-port groups (eg, Narcotics Anonymous), random

urine testing, and oral naltrexone therapy (a long-acting opioid antagonist).

Effective prevention strat-egies are difficult to formulate; “better” control

of drug availability is unlikely to deter a determined individual. It is

unlikely that education about the severe consequences of substance abuse will

bring new information to the potential drug-abusing physician. There remains

controversy regarding the rate at which anesthesia staff will experience recidi-vism.

Many experts argue for a “one strike and you’re out” policy for anesthesiology

residents who abuse injectable drugs. The decision as to whether a fully

trained and certified physician who has been dis-covered to abuse injectable

drugs should return to anesthetic practice after completing a rehabilitation

program varies and depends on the rules and tra-ditions of the practice group,

the medical center, the relevant medical licensing board, and the per-ceived

likelihood of recidivism. Physicians return-ing to practice following

successful completion of a program must be carefully monitored over the long

term, as relapses can occur years after apparent suc-cessful rehabilitation.

Alcohol abuse is a common problem among physicians and nurses, and anes-thesia

personnel are no exception. Interventions for alcohol abuse, as is true for

injectable drug abuse, must be carefully orchestrated. Guidance from the local

medical society or licensing authority is highly recommended.

4. Ionizing Radiation Exposure

The use of imaging equipment (eg,

fluoroscopy) during surgery and interventional radiologic proce-dures exposes

the anesthesiologist to the potentialrisks of ionizing radiation. The three

most important methods of minimizing radiationdoses are limiting total exposure

time during pro-cedures, using proper barriers, and maximizing the distance

from the source of radiation. Anesthesiolo-gists who routinely perform

fluoroscopic image guided invasive procedures should consider wearing

protective eyeware incorporating radiation shield-ing. Lead glass partitions or

lead aprons with thyroid shields are mandatory protection for all personnel who

are exposed to ionizing radiation. The inverse square law states that the

dosage of radiation varies inversely with the square of the distance. Thus, the

exposure at 4 m will be one-sixteenth that at 1 m. The maximum recommended

occupational whole-body exposure to radiation is 5 rem/yr. This can be

monitored with an exposure badge. The health impact on operating room personnel

of exposure to electromagnetic radiation remains unclear.

Related Topics