Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Perioperative & Critical Care Medicine: Anesthetic Complications

Anesthetic Complications: Peripheral Nerve Injury

PERIPHERAL NERVE INJURY

Nerve injury is a complication of being hospital-ized, with or without

surgery, regional, or general anesthesia. Peripheral nerve injury is a frequent

and vexing problem. In most cases, these injuries resolve within 6–12 weeks,

but some are permanent. Because peripheral neuropathies are commonly associated

(often incorrectly!) with failures of patient positioning, a review of

mechanisms and prevention is necessary.

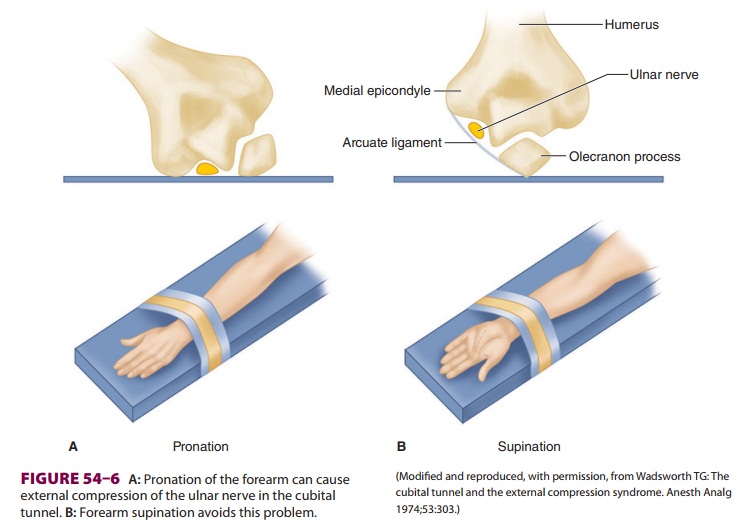

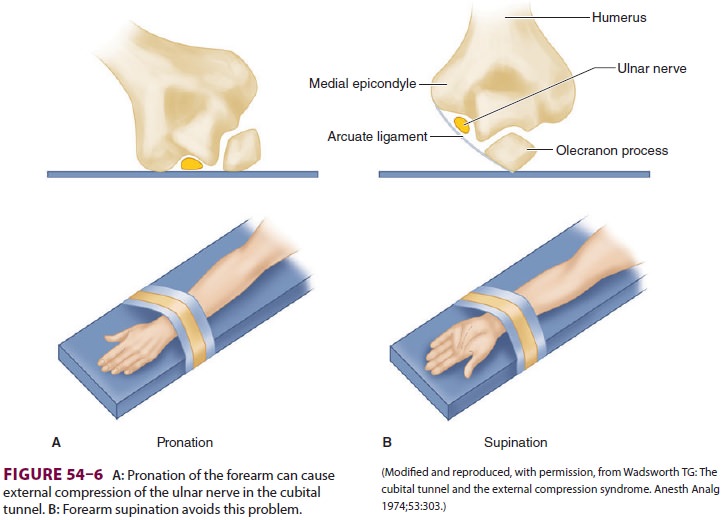

The most commonly injured peripheral nerve is

the ulnar nerve ( Figure 54–6).

In a retrospective study of over 1 million patients, ulnar neuropathy

(persisting for more than 3 months) occurred in approximately 1 in 2700

patients. Of interest, ini-tial symptoms were most frequently noted more than

24 hr after a surgical procedure. Risk factors included male gender, hospital

stay greater than 14 days, and very thin or obese body habitus. More than 50%

of these patients regained full sensory and motor function within 1 yr.

Anesthetic technique was not implicated as a risk factor; 25% of patients with

ulnar neuropathy underwent monitored care or lower extremity regional

technique. The ASA Closed Claims Project findings support most of these

results, including the delayed onset of symp-toms and the lack of relationship

between anesthe-sia technique and injury. This study also noted that many

neuropathies occurred despite notation of extra padding over the elbow area,

further negat-ing compression as a possible mechanism of injury. Finally, the

ASA Closed Claims Project investigators found no deviation from the standard of

care in the majority of patients who manifested nerve damage perioperatively.

The Role of Positioning

Other peripheral nerve injuries seem to be more closely related to positioning or surgical procedure. They may involve the peroneal nerve, the brachial plexus, or the femoral and sciatic nerves. External pressure on a nerve could compromise its perfusion, disrupt its cellular integrity, and eventually result in edema, ischemia, and necrosis. Pressure injuries are particularly likely when nerves pass through closed compartments or take a superficial course (eg, the peroneal nerve around the fibula). Lower extremity neuropathies, particularly those involving the pero-neal nerve, have been associated with such factors as extreme degrees (high) and prolonged (greater than 2 h) durations of the lithotomy position. But, these nerve injuries also sometimes occur when such con-ditions are not present. Other risk factors for lower extremity neuropathy include hypotension, thin body habitus, older age, vascular disease, diabetes, and cigarette smoking. An axillary (chest) “roll” is commonly used to reduce pressure on the inferior shoulder of patients in the lateral decubitus position. This roll should be located caudad to the axilla to prevent direct pressure on the brachial plexus and large enough to relieve any pressure from the mat-tress on the lower shoulder.

The data are convincing that some periph-eral

nerve injuries are not preventable. The risk of peripheral neuropathy should be

included in discussions leading to informed consent. When reasonable, patients

with contractures (or other causes of limited flexibility) can be positioned

before induction of anesthesia to check for feasibility and discomfort. Final

positioning should be evaluated prior to draping. In most circumstances, the

head and neck should be kept in a neutral position. Shoul-der braces to support

patients maintained in a Tren-delenberg position should be avoided if possible,

and shoulder abduction and lateral rotation should be minimized. The upper

extremities should not be extended greater than 90° at any joint. (There should

be no continuous external compression on the knee, ankle, or heel.) Although

injuries may still occur, additional padding may be helpful in vulnerable

areas. Documentation should include information on positioning, including the

presence of padding. Finally, patients who complain of sensory or motor

dysfunction in the postoperative period should be reassured that this is

usually a temporary condition. Motor and sensory function should be documented.

When symptoms persist for more than 24 hr, the patient should be referred to a

neurologist (or a physiatrist or hand surgeon) who is knowledgeable about

perioperative nerve damage for evaluation. Physiological testing, such as nerve

conduction and electromyographic studies, can be useful to docu-ment whether

nerve damage is a new or chronic condition. In the latter case, fibrillations

will be observed in chronically denervated muscles.

Complications Related to Positioning

Changes of body position have physiological

con-sequences that can be exaggerated in disease states. General and regional

anesthesia may limit the car-diovascular response to such a change. Even

posi-tions that are safe for short periods may eventually lead to complications

in persons who are not able to move in response to pain. For example, the

alco-holic patient who passes out on a hard floor or a park bench may awaken

with a brachial plexus injury. Similarly, regional and general anesthesia

abolish protective reflexes and predispose patients to injury.

Complications of postural hypotension, the most common physiological

consequence of posi-tioning, can be minimized by avoiding abrupt or extreme

position changes (eg, sitting up quickly), reversing the position if vital

signs deteriorate, keep-ing the patient well hydrated, and having vasoac-tive

drugs available to treat hypotension. Whereas maintaining a reduced level of

general anesthesia will decrease the likelihood of hypotension, light general

anesthesia will increase the likelihood that movement of the endotracheal tube

during posi-tioning will cause the patient to cough and become hypertensive.

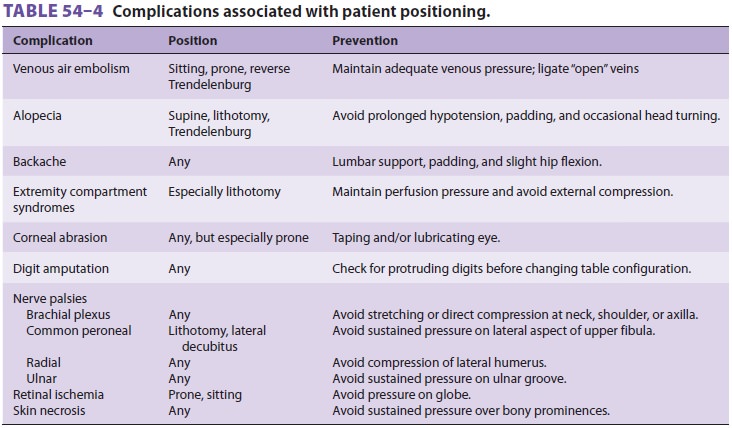

Many complications, including air embolism, blindness from sustained

pressure on the globe, and finger amputation following a crush injury, can be

caused by improper patient positioning ( Table 54–4). These

complications are best prevented by evaluat-ing the patient’s postural

limitations during the pre-anesthetic visit; padding pressure points,

susceptible nerves, and any area of the body that will possibly be in contact with the operating table or its

attach-ments; avoiding flexion or extension of a joint to its limit; having an

awake patient assume the position

to ensure comfort; and understanding the poten-tial complications of

each position. Monitors must often be disconnected during patient

repositioning, making this a time of greater risk for unrecognized hemodynamic derangement.

Compartment syndromes can result from

hemorrhage into a closed space following a vascu-lar puncture or prolonged

venous outflow obstruc-tion, particularly when associated with hypotension. In

severe cases, this may lead to muscle necrosis, myoglobinuria, and renal

damage, unless the pres-sure within the extremity compartment is relieved by

surgical decompression (fasciotomy) or in the abdominal compartment by

laparotomy.

Related Topics