Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Perioperative & Critical Care Medicine: Anesthetic Complications

Anesthetic Complications: Equipment Problems

EQUIPMENT PROBLEMS

“Equipment problems” is probably a misnomer;

the ASA Closed Claims Project review of 72 claims involving gas delivery

systems found that equipment misuse was

three times more commonthanequip-ment malfunction.

The majority (76%) of adverse

outcomes associated with gas delivery

problems were either death or permanent neurological damage.

Errors in drug administration also typically involve human error. It has

been suggested that as many as 20% of the drug doses given to hospitalized

patients are incorrect. Errors in drug administration account for 4% of cases

in the ASA Closed Claims Project, which found that errors resulting in claims

were most frequently due to either incorrect dosage or unintentional

administration of the wrong drug (syringe swap). In the latter category,

accidental administration of epinephrine proved particularly dangerous.

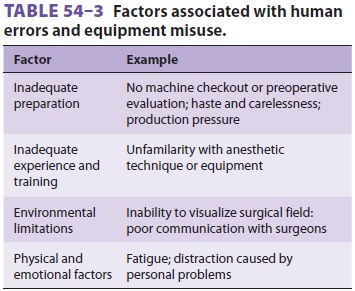

Another type of human error occurs when the

most critical problem is ignored because attention is inappropriately focused

on a less important problem or an incorrect solution (fixation error). Serious

anesthetic mishaps are often associated with distrac-tions and other factors

(Table 54–3). The impact of most equipment failures is decreased or avoided

when the problem is identified during a routine preoperative checkout performed

by adequatelytrained personnel. Many anesthetic fatalities occur only after a

series of coincidental circumstances, misjudgments, and technical errors

coincide (mishap chain).

Prevention

Strategies to reduce the incidence of serious anes-thetic complications

include better monitoring and anesthetic techniques, improved education, more

comprehensive protocols and standards of prac-tice, and active risk management

programs. Better monitoring and anesthetic techniques imply more comprehensive

monitoring and ongoing patient assessments and better designed anesthesia equip-ment

and workspaces. The fact that most accidents occur during the maintenance phase

of anesthesia— rather than during induction or emergence—implies a failure of

vigilance.

Inspection, palpation, percussion, and

ausculta-tion of the patient provide important information. Instruments should

supplement (but never replace) the anesthesiologist’s own senses. To minimize

errors in drug administration, drug syringes and ampoules in the workspace

should be restricted to those needed for the current specific case. Drugs

should be consistently diluted to the same concen-tration in the same way for

each use, and they should be clearly labeled. Computer systems for scanning

bar-coded drug labels are available that may help to reduce medication errors.

The conduct of all anes-thetics should follow a predictable pattern by which

the anesthetist actively surveys the monitors, the surgical field, and the

patient on a recurrent basis. In particular, patient positioning should be

frequently reassessed to avoid the possibility of compression or stretch

injuries. When surgical necessity requires patients to be placed in positions

where harm may occur or when hemodynamic manipulations (eg, deliberate

hypotension) are requested or required, the anesthesiologist should note on the

record the surgical request and remind the surgeon of any potential risks to

the patient.

Related Topics