Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Perioperative & Critical Care Medicine: Anesthetic Complications

Adverse Anesthetic Outcomes

ADVERSE ANESTHETIC OUTCOMES

Incidence

There are several reasons why it is difficult

to accurately measure the incidence of adverse anesthesia-related outcomes.

First, it is often difficult to determine whether the cause of a poor outcome

is the patient’s underlying disease, the surgical proce-dure, or the anesthetic

management. In some cases, all three factors contribute to a poor outcome.

Clini-cally important measurable outcomes are relatively rare after elective

anesthetics. For example, death isclear endpoint, and perioperative

deaths do occur with some regularity. But, because deaths attribut-able to

anesthesia are much rarer, a very large series of patients must be studied to

assemble conclusions that have statistical significance. Nonetheless, many

studies have attempted to determine the incidence of complications due to

anesthesia. Unfortunately, studies vary in criteria for defining an

anesthesia-related adverse outcome and are limited by retro-spective analysis.

Perioperative mortality is usually defined as

death within 48 hr of surgery. It is clear that most perioperative fatalities

are due to the patient’s preop-erative disease or the surgical procedure. In a

study conducted between 1948 and 1952, anesthesia mor-tality in the United

States was approximately 5100 deaths per year or 3.3 deaths per 100,000 popula-tion.

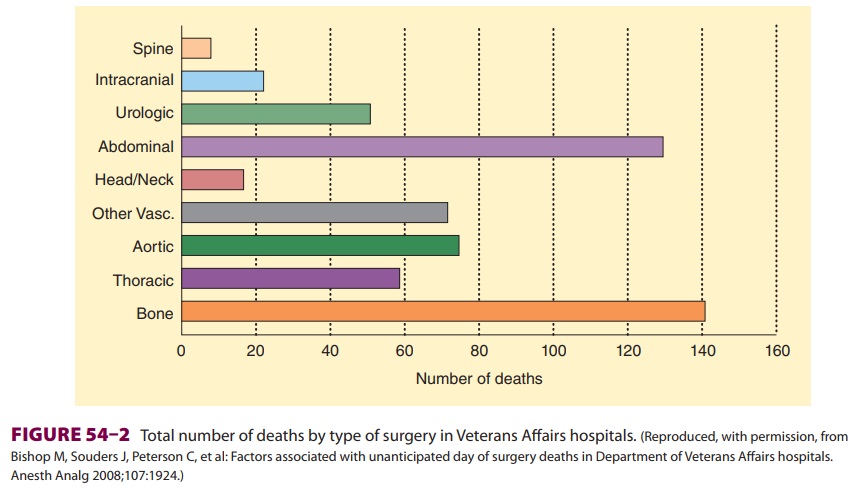

A review of cause of death files in the United States showed that the rate of

anesthesia-related deaths was 1.1/1,000,000 population or 1 anesthetic death

per 100,000 procedures between 1999 and 2005 (Figure 54–1). These results suggest a 97% decrease in anesthesia mortality since

the 1940s. However, a 2002 study reported an estimated rate of 1 death per

13,000 anesthetics. Due to differences in methodology, there are discrepancies

in the lit-erature as to how well anesthesiology is doing in achieving safe

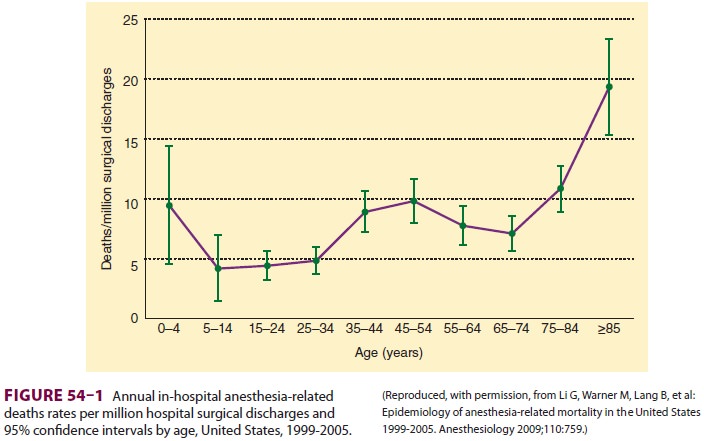

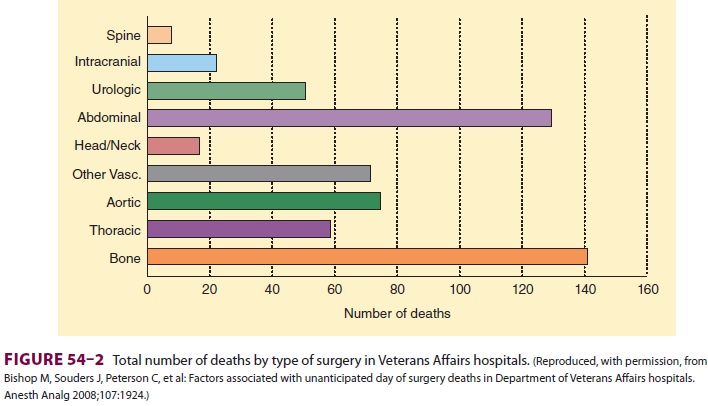

practice. In a 2008 study of 815,077 patients (ASA class 1, 2, or 3) who

underwent elec-tive surgery at US Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals, the

mortality rate was 0.08% on the day of surgery. The strongest association with

periop-erative death was the type of surgery (Figure 54–2). Other factors associated with increased risk of death

included dyspnea, reduced albumin concentrations, increased bilirubin, and increased creatinine con-centrations. A subsequent review of the 88 deaths that occurred on the surgical day noted that 13 ofthe patients might have benefitted from better anes-thesia care, and estimates suggest that death might have been prevented by better anesthesia practice in 1 of 13,900 cases. Additionally, this study reported that the immediate postsurgical period tended to be the time of unexpected mortality. Indeed, often missed opportunities for improved anesthetic care occur following complications when “failure to res-cue” contributes to patient demise.

American Society of Anesthesiologists Closed Claims Project

The goal of the ASA Closed Claims Project is

to identify common events leading to claims in anes-thesia, patterns of injury,

and strategies for injury prevention. It is a collection of closed malpractice

claims that provides a “snapshot” of anesthesia liabil-ity rather than a study

of the incidence of anesthetic complications, as only events that lead to the

filing of a malpractice claim are considered. The Closed Claims Project

consists of trained physicians who review claims against anesthesiologists

represented by some US malpractice insurers. The number of claims in the

database continues to rise each year as new claims are closed and reported. The

claims are grouped according to specific damaging events and complication type.

Closed Claims Project analyses have been reported for airway injury, nerve

injury, awareness, and so forth. These analyses provide insights into the

circumstances that result in claims; however, the incidence of a complication

cannot be determined from closed claim data, because we know neither the actual

incidence of the complica-tion (some with the complication may not file suit),

nor how many anesthetics were performed for which the particular complication

might possibly develop. Other similar analyses have been performed in the

United Kingdom, where National Health Service (NHS) Litigation Authority claims

are reviewed.

Causes

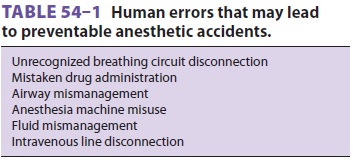

Anesthetic mishaps can be categorized as

preventable or unpreventable. Examples ofthe latter include sudden death

syndrome, fatal idiosyncratic drug reactions, or any poor outcome that occurs

despite proper management. How-ever, studies of anesthetic-related deaths or

near misses suggest that many accidents are prevent-able. Of these preventable

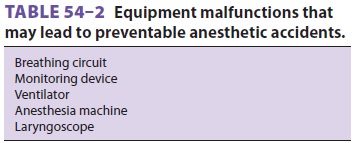

incidents, most involve human error (Table 54–1), as opposed to equipment

malfunctions (Table 54–2). Unfortunately, some rate of human error is inevitable, and a prevent-able

accident is not necessarily evidence of incom-petence. During the 1990s, the

top three causes for claims in the ASA Closed Claims Project were death (22%),

nerve injury (18%), and brain damage (9%). In a 2009 report based on an

analysis of NHS liti-gation records, anesthesia-related claims accounted for

2.5% of total claims filed and 2.4% of the value of all NHS claims. Moreover,

regional and obstetri-cal anesthesia were responsible for 44% and 29%,

respectively, of anesthesia-related claims filed. The authors of the latter

study noted that there are two ways to examine data related to patient harm:

critical incident and closed claim analyses. Clinical (or criti-cal) incident

data consider events that either cause harm or result in a “near-miss.” Comparison

between clinical incident datasets and closed claims analyses demonstrates that

not all critical events generate claims and that claims may be filed in the

absence of negligent care. Consequently, closed claims reports must always be

considered in this context.

Related Topics