Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Child and Adolescent Disorders

Mental Health Promotion - Conduct Disorder

MENTAL HEALTH PROMOTION

Parental behavior profoundly influences children’s behavior.

Parents who engage in risky behaviors such as smoking, drinking, and ignoring

their health are more likely to have children who also engage in risky

behaviors, including early unprotected sex. Group-based parenting classes are

effective to deal with problem behaviors in children and to prevent later

development of conduct disorders (Turner & Sanders, 2006).

Eisen, Raleigh, and Neuhoff (2008) reported that an early

intervention program for children at risk for anxiety disorders improved

behavior. The program consisted of parent sessions, child anxiety management,

parent–child sessions that emphasized coping skills, and graduated exposure to

anxiety-provoking situations.

The SNAP-IV teacher and parent rating scale (Swanson, 2000) is an

assessment tool that can be used for initial evaluation in many areas of

concern such as ADHD, oppo-sitional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder,

and depression. Such tools can identify problems or potential problems that

signal a need for further evalua-tion and follow-up. Early detection and

successful inter-vention are often the key to mental health promotion.

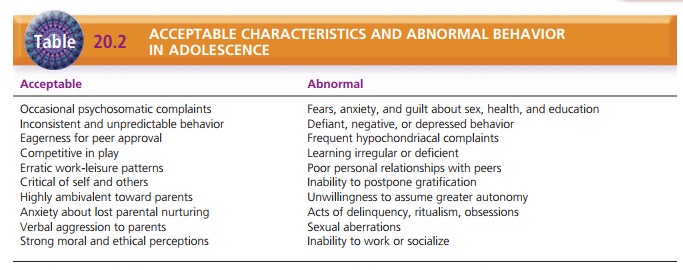

Oppositional Defiant Disorder

ODD consists of an enduring pattern of uncooperative, defiant, and

hostile behavior toward authority figures without major antisocial violations.

A certain level of oppositional behavior is common in children and

adoles-cents; indeed, it is almost expected at some phases such as 2 to 3 years

of age and in early adolescence. Table 20.2 contrasts acceptable characteristics

with abnormal behav-ior in adolescents. ODD is diagnosed only when behaviors

are more frequent and intense than in unaffected peers and cause dysfunction in

social, academic, or work situations. This disorder is diagnosed in about 5% of

the population and occurs equally among male and female adolescents. Most

authorities believe that genes, temperament, and adverse social conditions

interact to create ODD. Twenty-five percent of people with this disorder

develop conduct disorder; 10% are diagnosed with antisocial personality

disorder as adults (Thomas, 2005). ODD is often comor-bid with other

psychiatric disorders such as ADHD, anxi-ety, and affective disorders that need

to be treated as well. Treatment approaches for ODD are similar to those used

for conduct disorder.

Feeding and Eating Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood

The disorders of feeding and eating included in this cate-gory are

persistent in nature and are not explained by underlying medical conditions.

They include pica, rumi-nation disorder, and feeding disorder.

Pica

Pica is persistent ingestion of

nonnutritive substances such as

paint, hair, cloth, leaves, sand, clay, or soil. Pica is com-monly seen in

children with mental retardation; it occasion-ally occurs in pregnant women. It

comes to the clinician’s attention only if a medical complication develops such

as a bowel obstruction or an infection or if a toxic condition develops such as

lead poisoning. In most instances, the behavior lasts for several months and

then remits.

Rumination Disorder

Rumination disorder is the repeated regurgitation

and rechew-ing of food. The child brings partially digested food up into the

mouth and usually rechews and reswallows the food. The regurgitation does not

involve nausea, vomiting, or any medical condition (APA, 2000). This disorder

is relatively uncommon and occurs more often in boys than in girls; it results

in malnutrition, weight loss, and even death in about 25% of affected infants.

In infants, the disorder frequently remits spontaneously, but it may continue

in severe cases.

Feeding Disorder

Feeding disorder of infancy or early childhood is character-ized by

persistent failure to eat adequately, which results in significant weight loss

or failure to gain weight. Feeding dis-order is equally common in boys and

girls and occurs most often during the first year of life. Estimates are that

5% of all pediatric hospital admissions are for failure to gain weight, and up

to 50% of those admissions reflect a feeding disorder with no predisposing medical condition. In

severe cases, malnutrition and death can result, but most children have

improved growth after some time (APA, 2000).

Tic Disorders

A tic is a sudden,

rapid, recurrent, nonrhythmic, stereo-typed motor movement or vocalization

(APA, 2000). Tics can be suppressed but not indefinitely. Stress exacerbates

tics, which diminish during sleep and when the person is engaged in an

absorbing activity. Common simple motor tics include blinking, jerking the

neck, shrugging the shoulders, grimacing, and coughing. Common simple vocal

tics include clearing the throat, grunting, sniffing, snorting, and barking.

Complex vocal tics include repeat-ing words or phrases out of context,

coprolalia (use of socially unacceptable words, frequently obscene), palilalia

(repeating one’s own sounds or words), and echolalia (repeating the last-heard

sound, word, or phrase; APA, 2000). Complex motor tics include facial gestures,

jump-ing, or touching or smelling an object.

Tic disorders tend to run in families. Abnormal trans-mission of

the neurotransmitter dopamine is thought to play a part in tic disorders

(Scahill & Leckman, 2005). Tic disorders usually are treated with

risperidone (Risperdal) or olanzapine (Zyprexa), which are atypical

antipsychot-ics. It is important for clients with tic disorders to get plenty

of rest and to manage stress because fatigue and stress increase symptoms.

Tourette’s Disorder

Tourette’s disorder involves multiple motor tics

and one or more vocal tics, which

occur many times a day for more than 1 year. The complexity and severity of the

tics change over time, and the person experiences almost all the pos-sible tics

described previously during his or her lifetime. The person has significant

impairment in academic, social, or occupational areas and feels ashamed and

self- conscious. This rare disorder (4 or 5 in 10,000) is more common in boys

and is usually identified by 7 years of age. Some people have lifelong

problems; others have no symptoms after early adulthood (APA, 2000).

Chronic Motor or Tic Disorder

Chronic motor or vocal tic differs from Tourette’s disorder in that

either the motor or the vocal tic is seen, but not both. Transient tic disorder

may involve single or multiple vocal or motor tics, but the occurrences last no

longer than 12 months.

Elimination Disorders

Encopresis is the repeated passage of

feces into inappro-priate places such as clothing or the floor by a child who

is at least 4 years of age either chronologically or develop-mentally. It is

often involuntary, but it can be intentional. Involuntary encopresis usually is

associated with constipation that occurs for psychological, not medical,

reasons. Intentional encopresis often is associated with ODD or conduct

disorder.

Enuresis is the repeated voiding of

urine during the day or at night

into clothing or bed by a child at least 5 years of age either chronologically

or developmentally. Most often enuresis is involuntary; when intentional, it is

asso-ciated with a disruptive behavior disorder. Seventy-five percent of

children with enuresis have a first-degree rela-tive who had the disorder. Most

children with enuresis do not have a coexisting mental disorder.

Both encopresis and enuresis are more common in boys than in girls;

1% of all 5 year olds have encopresis, and 5% of all 5 year olds have enuresis.

Encopresis can persist with intermittent exacerbations for years; it is rarely

chronic. Most children with enuresis are continent by adolescence; only 1% of

all cases persist into adulthood.

Impairment associated with elimination disorders depends on the

limitations on the child’s social activities, effects on self-esteem, degree of

social ostracism by peers, and anger, punishment, and rejection on the part of

par-ents or caregivers (APA, 2000).

Enuresis can be treated effectively with imipramine (Tof-ranil), an

antidepressant with a side effect of urinary reten-tion. Both elimination

disorders respond to behavioral approaches such as a pad with a warning bell

and to positive reinforcement for continence. For children with a disruptive

behavior disorder, psychological treatment of that disorder may improve the

elimination disorder (Mikkelsen, 2005).

Other Disorders of Infancy, Childhood, or Adolescence

Separation Anxiety Disorder

Separation anxiety disorder is characterized by anxiety exceeding

that expected for developmental level related to separation from the home or

those to whom the child is attached (APA, 2000). When apart from attachment

fig-ures, the child insists on knowing their whereabouts and may need frequent

contact with them, such as phone calls. These children are miserable away from

home and may fear never seeing their homes or loved ones again. They often

follow parents like a shadow, cannot be in a room alone, and have trouble going

to bed at night unless some-one stays with them. Fear of separation may lead to

avoid-ance behaviors such as refusal to attend school or go on errands.

Separation anxiety disorder often is accompanied by nightmares and multiple

physical complaints such as headaches, nausea, vomiting, and dizziness.

Separation anxiety disorders are thought to result from an

interaction between temperament and parenting behav-iors. Inherited temperament

traits such as passivity, avoid-ance, fearfulness, or shyness in novel

situations coupled with parenting behaviors that encourage avoidance as a way

to deal with strange or unknown situations are thought to cause anxiety in the

child (Bernstein & Layne, 2005).

Selective Mutism

Selective mutism is characterized by persistent failure to speak in

social situations where speaking is expected such as school (APA, 2000).

Children may communicate by gestures, nodding or shaking the head, or

occasionally one-syllable vocalizations in a voice different from their natural

voice. These children are often excessively shy, socially withdrawn or

isolated, and clinging; they may have temper tantrums. Selective mutism is rare

and slightly more common in girls than in boys. It usually lasts only a few

months but may persist for years.

Reactive Attachment Disorder

Reactive attachment disorder involves a markedly dis-turbed and developmentally

inappropriate social related-ness in most situations. This disorder usually

begins before 5 years of age and is associated with grossly patho-genic care

such as parental neglect, abuse, or failure to meet the child’s basic physical

or emotional needs. Repeated changes in primary caregivers, such as multiple

foster care placements, also can prevent the formation of stable attachments

(APA, 2000). The disturbed social relatedness may be evidenced by the child’s

failure to ini-tiate or respond to social interaction (inhibited type) or

indiscriminate sociability or lack of selectivity in choice of attachment

figures (disinhibited type). In the first type, the child will not cuddle or

desire to be close to anyone. In the second type, the child’s response is the

same to a stranger or to a parent.

Initially, treatment focuses on the child’s safety, includ-ing

removal of the child from the home if neglect or abuse is found. Individual and

family therapy (either with par-ents or foster caregivers) is most effective.

With early identification and effective intervention, remission or considerable

improvements can be attained. Otherwise, the disorder follows a continuous

course, with relation-ship problems persisting into adulthood.

Stereotypic Movement Disorder

Stereotypic movement disorder is associated with many genetic,

metabolic, and neurologic disorders and often accompanies mental retardation.

The precise cause is unknown. It involves repetitive motor behavior that is

nonfunctional and either interferes with normal activities or results in

self-injury requiring medical treatment (APA, 2000). Stereotypic movements may include waving, rock-ing, twirling

objects, biting fingernails, banging the head, biting or hitting oneself, or

picking at the skin or body orifices. Generally speaking, the more severe the

retarda-tion, the higher the risk for self-injury behaviors. Stereo-typic

movement behaviors are relatively stable over time but may diminish with age

(Shah, 2005).

No specific treatment has been shown effective. Clomipramine

(Anafranil) and desipramine (Norpramin) are effective in treating severe nail

biting; haloperidol (Haldol) and chlorpromazine (Thorazine) have been effective

for stereotypic movement disorder associated with mental retardation and autistic

disorder.

Related Topics