Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Child and Adolescent Disorders

Conduct Disorder

CONDUCT DISORDER

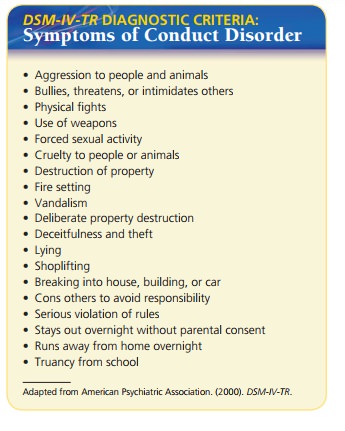

Conduct disorder is characterized by

persistent antisocial behavior in

children and adolescents that significantly impairs their ability to function

in social, academic, or occupational areas. Symptoms are clustered in four

areas:

Onset and Clinical Course

Two subtypes of conduct disorder are based on age at onset. The

childhood-onset type involves symptoms before 10 years of age, including

physical aggression toward oth-ers and disturbed peer relationships. These

children are more likely to have persistent conduct disorder and to develop

antisocial personality disorder as adults. Adoles-cent-onset type is defined by

no behaviors of conduct dis-order until after 10 years of age. These

adolescents are less likely to be aggressive, and they have more normal peer

relationships. They are less likely to have persistent con-duct disorder or

antisocial personality disorder as adults (APA, 2000).

Conduct disorders can be classified as mild, moderate, or severe

(APA, 2000):

·

Mild: The person has some conduct

problems that cause relatively minor

harm to others. Examples in-clude lying, truancy, and staying out late without

permission.

·

Moderate: The number of conduct

problems increases as does the amount

of harm to others. Examples include vandalism and theft.

·

Severe: The person has many conduct

problems that cause considerable harm

to others. Examples include forced sex, cruelty to animals, use of a weapon,

bur-glary, and robbery.

The course of conduct disorder is variable. People with the adolescent-onset

type or mild problems can achieve adequate social relationships and academic or

occupational success as adults. Those with the childhood-onset type or more

severe problem behaviors are more likely to develop antisocial personality

disorder as adults. Even those who do not have antisocial personality disorder

may lead trou-bled lives with difficult interpersonal relationships, unhealthy

lifestyles, and an inability to support themselves (Thomas, 2005).

Etiology

Researchers generally accept that genetic vulnerability,

environmental adversity, and factors like poor coping interact to cause the

disorder. Risk factors include poor parenting, low academic achievement, poor

peer relation-ships, and low self-esteem; protective factors include resil-ience,

family support, positive peer relationships, and good health (Thomas, 2005).

There is a genetic risk for conduct disorder, although no specific

gene marker has been identified (Thomas, 2005). The disorder is more common in

children who have a sibling with conduct disorder or a parent with anti-social

personality disorder, substance abuse, mood disor-der, schizophrenia, or ADHD

(APA, 2000).

A lack of reactivity of the autonomic nervous system has been found

in children with conduct disorder; this nonresponsiveness is similar to adults

with antisocial per-sonality disorder. The abnormality may cause more

aggression in social relationships as a result of decreased normal avoidance or

social inhibitions. Research into the role of neurotransmitters is promising

(Thomas, 2005).

Poor family functioning, marital discord, poor parent-ing, and a

family history of substance abuse and psychiat-ric problems are all associated

with the development of conduct disorder. Prenatal exposure to alcohol causes

an increased risk for conduct disorder (Disney, Iacono, McGue, Tully, &

Legrand, 2008). Child abuse is an espe-cially significant risk factor. The

specific parenting pat-terns considered ineffective are inconsistent parental

responses to the child’s demands and giving in to demands as the child’s

behavior escalates. Exposure to violence in the media and community is a

contributing factor for the child at risk in other areas. Socioeconomic

disadvantages, such as inadequate housing, crowded conditions, and pov-erty, also

increase the likelihood of conduct disorder in at-risk children (McGuinness,

2006).

Academic underachievement, learning disabilities, hyper-activity,

and problems with attention span are all associated with conduct disorder.

Children with conduct disorder have difficulty functioning in social

situations. They lack the abil-ities to respond appropriately to others and to

negotiate con-flict, and they lose the ability to restrain themselves when

emotionally stressed. They are often accepted only by peers with similar

problems (Thomas, 2005).

Cultural Considerations

Concerns have been raised that “difficult” children may be

mistakenly labeled as having conduct disorder. Knowing the client’s history and

circumstances is essential for accu-rate diagnosis. In high-crime areas,

aggressive behavior may be protective and not necessarily indicative of

con-duct disorder. In immigrants from war-ravaged countries, aggressive

behavior may have been necessary for survival, so these individuals should not

be diagnosed with conduct disorder (APA, 2000).

Treatment

Many treatments have been used for conduct disorder with only

modest effectiveness. Early intervention is more effec-tive, and prevention is

more effective than treatment. Dra-matic interventions, such as “boot camp” or

incarceration, have not proved effective and may even worsen the situa-tion

(Thomas, 2005). Treatment must be geared toward the client’s developmental age;

no one treatment is suitable for all ages. Preschool programs, such as Head

Start, result in lower rates of delinquent behavior and conduct disor-der

through use of parental education about normal growth and development,

stimulation for the child, and parental support during crises.

For school-aged children with conduct disorder, the child, family,

and school environment are the focus of treatment. Techniques include parenting

education, social

Adolescents rely less on their parents and more on peers, so

treatment for this age group includes individual therapy. Many adolescent clients

have some involvement with the legal system as a result of criminal behavior,

and consequently they may have restrictions on their freedom. Use of alcohol

and other drugs plays a more significant role for this age group; any treatment

plan must address this issue. The most promising treatment approach includes

keeping the client in his or her environment with family and individual

therapies. The plan usually includes conflict reso-lution, anger management,

and teaching social skills.

Medications alone have little effect but may be used in conjunction

with treatment for specific symptoms. For example, the client who presents a

clear danger to others may be prescribed an antipsychotic medication, or a

client with a labile mood may benefit from lithium or another mood stabilizer

such as carbamazepine (Tegretol) or valp-roic acid (Depakote) (Thomas, 2005).

Related Topics