Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Child and Adolescent Disorders

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

ATTENTION DEFICIT HYPERACTIVITY

DISORDER

Attention deficit

hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is characterized by inattentiveness, overactivity,

and impulsiveness. ADHD is a common disorder, especially in boys, and probably

accounts for more child mental health referrals than any other single disorder

(Hechtman, 2005). The essential feature of ADHD is a persistent pattern of

inatten-tion and/or hyperactivity and impulsivity more common than generally

observed in children of the same age.

ADHD affects an estimated 3% to 5% of all school-aged children. The

ratio of boys to girls ranges from 3:1 in non-clinical settings to 9:1 in

clinical settings (Hechtman, 2005). To avoid overdiagnosis of ADHD, a qualified

spe-cialist such as a pediatric neurologist or a child psychia-trist must

conduct the evaluation for ADHD. Children who are very active or hard to handle

in the classroom can be diagnosed and treated mistakenly for ADHD. Some of

these overly active children may suffer from psychosocial stressors at home,

inadequate parenting, or other psychiatric

Onset and Clinical Course

ADHD usually is identified and diagnosed when the child begins

preschool or school, although many parents report problems from a much younger

age. As infants, children with ADHD are often fussy and temperamental and have

poor sleeping patterns. Toddlers may be described as “always on the go” and

“into everything,” at times disman-tling toys and cribs. They dart back and

forth, jump and climb on furniture, run through the house, and cannot tol-erate

sedentary activities such as listening to stories. At this point in a child’s

development, it can be difficult for parents to distinguish normal active

behavior from exces-sive hyperactive behavior.

By the time the child starts school, symptoms of ADHD begin to

interfere significantly with behavior and perfor-mance (Dang, Warrington, Tung,

Baker, & Pan, 2007). The child fidgets constantly, is in and out of

assigned seats, and makes excessive noise by tapping or playing with pen-cils

or other objects. Normal environmental noises, such as someone coughing,

distract the child. He or she cannot listen to directions or complete tasks.

The child interrupts and blurts out answers before questions are completed.

Academic performance suffers because the child makes hurried,

careless mistakes in schoolwork, often loses or forgets homework assignments,

and fails to follow directions.

Socially, peers may ostracize or even ridicule the child for his or

her behavior. Forming positive peer relation-ships is difficult because the

child cannot play coopera-tively or take turns and constantly interrupts others

(APA, 2000). Studies have shown that both teachers and peers perceive children

with ADHD as more aggressive, more bossy, and less likable (Hechtman, 2005).

This perception results from the child’s impulsivity, inability to share or

take turns, tendency to interrupt, and failure to listen to and follow

directions. Thus, peers and teachers may exclude the child from activities and

play, may refuse to socialize with the child, or may respond to the child in a

harsh, punitive, or rejecting manner.

Approximately two thirds of children diagnosed with ADHD continue

to have problems in adolescence. Typical impulsive behaviors include cutting

class, getting speed-ing tickets, failing to maintain interpersonal

relationships, and adopting risk-taking behaviors, such as using drugs or

alcohol, engaging in sexual promiscuity, fighting, and vio-lating curfew. Many

adolescents with ADHD have disci-pline problems serious enough to warrant

suspension or expulsion from high school (Hechtman, 2005). The sec-ondary

complications of ADHD, such as low self-esteem and peer rejection, continue to

pose serious problems.

Previously, it was believed that children outgrew ADHD, but it is

now known that ADHD can persist into adulthood. Estimates are that 30% to 50%

of children with ADHD have symptoms that continue into adulthood. In one study,

adults who had been treated for hyperactivity 25 years ear-lier were three to

four times more likely than their brothers to experience nervousness,

restlessness, depression, lack of friends, and low frustration tolerance.

Approximately 70% to 75% of adults with ADHD have at least one coexisting

psychiatric diagnosis, with social phobia, bipolar disorder, major depression,

and alcohol dependence being the most common (Antai-Otong, 2008).

Etiology

Although much research has taken place, the definitive causes of

ADHD remain unknown. There may be cortical-arousal, information-processing, or

maturational abnor-malities in the brain (Rowe & Hermens, 2006). Combined

factors, such as environmental toxins, prenatal influences, heredity, and

damage to brain structure and functions, are likely responsible (Hechtman,

2005). Prenatal exposure to alcohol, tobacco, and lead and severe malnutrition

in early childhood increase the likelihood of ADHD. Although the relation

between ADHD and dietary sugar and vitamins has been studied, results have been

incon-clusive ( Hechtman, 2005).

Brain images of people with ADHD suggest decreased metabolism in

the frontal lobes, which are essential for attention, impulse control,

organization, and sustained goal-directed activity. Studies also have shown

decreased blood perfusion of the frontal cortex in children with ADHD and

frontal cortical atrophy in young adults with a history of childhood ADHD.

Another study showed decreased glucose use in the frontal lobes of parents of

children with ADHD who had ADHD themselves (Hechtman, 2005). Evidence is not

conclusive, but research in these areas seems promising.

There seems to be a genetic link for ADHD that is most likely

associated with abnormalities in catecholamine and possibly serotonin

metabolism. Having a first-degree rela-tive with ADHD increases the risk of the

disorder by four to five times more than that of the general population

(Hechtman, 2005). Despite the strong evidence support-ing a genetic

contribution, there are also sporadic cases of ADHD with no family history of

ADHD; this furthers the theory of multiple contributing factors.

Risk factors for ADHD include family history of ADHD; male

relatives with antisocial personality disorder or alco-holism; female relatives

with somatization disorder; lower socioeconomic status; male gender; marital or

family dis-cord, including divorce, neglect, abuse, or parental depri-vation;

low birth weight; and various kinds of brain insult (Hechtman, 2005).

Cultural Considerations

ADHD is known to occur in various cultures. It is more prevalent in

Western cultures, but that may be the result of different diagnostic practices

rather than the actual differ-ences in existence (APA, 2000).

The Child Behavior Checklist, Teacher Report Form, and Youth Self

Report (for ages 11 to 18 years) are rating scales frequently used to determine

problem areas and competencies. These scales are often part of a comprehen-sive

assessment of ADHD in children. They have been determined to be culturally

competent and are widely used in various countries (King et al., 2005).

Pierce and Reid (2004) found that an increasing number of children

from culturally diverse groups are diagnosed with ADHD. They believe this

increase may represent overidentification of ADHD in culturally diverse

children and urge practitioners to consider cultural con-text before making the

diagnosis.

Yeh, Hough, McCabe, Lau, and Garland (2004) stud-ied parental

beliefs about the causes of mental illness in their children. They found that

African-American, Asian/ Pacific Islander American, and Latino parents were

less likely to endorse biopsychosocial causes of mental illness than

non-Hispanic white parents and were more likely to believe in sociologic

causes. The authors believe this may affect participation in and compliance

with prescribed treatment.

Treatment

No one treatment has been found to be effective for ADHD; this

gives rise to many different approaches such as sugar-controlled diets and

megavitamin therapy. Parents need to know that any treatment heralded as the

cure for ADHD is probably too good to be true (Hechtman, 2005). ADHD is

chronic; goals of treatment involve managing symptoms, reducing hyperactivity

and impulsivity, and increasing the child’s attention so that he or she can

grow and develop normally. The most effective treatment combines pharma-cotherapy

with behavioral, psychosocial, and educational interventions (Dang et al.,

2007).

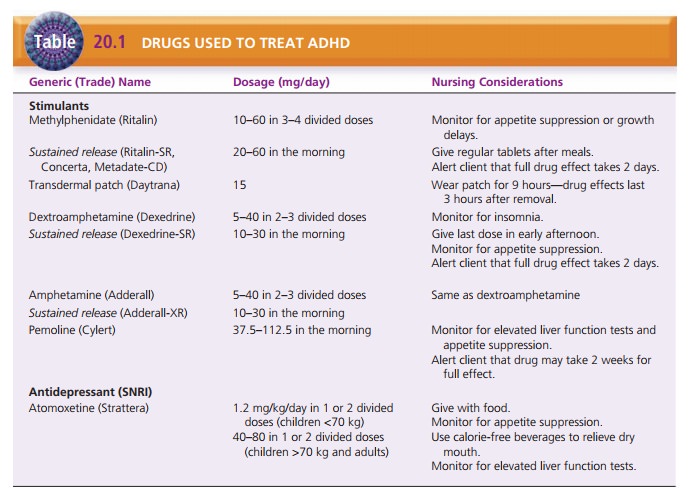

Psychopharmacology

Medications often are effective in decreasing hyperactivity and

impulsiveness and improving attention; this enables the child to participate in

school and family life. The most common medications are methylphenidate

(Ritalin) and an amphetamine compound (Adderall) (Hechtman, 2005; Lehne, 2006).

Methylphenidate is effective in 70% to 80% of children with ADHD; it reduces

hyperactivity, impulsiv-ity, and mood lability and helps the child to pay

attention more appropriately. Dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine) and pemoline

(Cylert) are other stimulants used to treat ADHD. The most common side effects

of these drugs are insomnia, loss of appetite, and weight loss or failure to

gain weight. Methylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, and amphetamine compounds are

also available in a sustained-release form taken once daily; this eliminates

the need for additional doses when the child is at school. Methylphenidate is

also available in a daily transdermal patch, marketed

Giving stimulants during daytime hours usually effec-tively combats

insomnia. Eating a good breakfast with the morning dose and substantial

nutritious snacks late in the day and at bedtime helps the child to maintain an

adequate dietary intake. When stimulant medications are not effective or their

side effects are intolerable, anti-depressants are the second choice for

treatment . Atomoxetine (Strattera) is the only nonstim-ulant drug specifically

developed and tested by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of

ADHD. It is an antidepressant, specifically a selective norepi-nephrine

reuptake inhibitor. The most common side effects in children during clinical

trials were decreased appetite, nausea, vomiting, tiredness, and upset

stom-ach. In adults, side effects were similar to those of other

antidepressants, including insomnia, dry mouth, urinary retention, decreased

appetite, nausea, vomiting, dizzi-ness, and sexual side effects. In addition,

atomoxetine can cause liver damage, so individuals taking the drug need to have

liver function tests periodically (Cheng, Chen, Ko, & Ng, 2007). Table 20.1

lists drugs, dosages, and nursing considerations for clients with ADHD.

Strategies for Home and School

Medications do not automatically improve the child’s aca-demic

performance or ensure that he or she makes friends. Behavioral strategies are

necessary to help the child to master appropriate behaviors. Environmental

strategies at school and home can help the child to succeed in those settings.

Educating parents and helping them with parent-ing strategies are crucial

components of effective treatment of ADHD. Effective approaches include

providing consis-tent rewards and consequences for behavior, offering

con-sistent praise, using time-out, and giving verbal reprimands. Additional

strategies are issuing daily report cards for behavior and using point systems

for positive and negative behavior (Hechtman, 2005).

In therapeutic play,

play techniques are used to under-stand the child’s thoughts and feelings and

to promote communication. This should not be confused with play therapy, a

psychoanalytic technique used by psychiatrists. Dramatic play is acting out an

anxiety-producing situation such as allowing the child to be a doctor or use a

stetho-scope or other equipment to take care of a patient (a doll). Play

techniques to release energy could include pounding pegs, running, or working

with modeling clay. Creative play techniques can help children to express

themselves, for example, by drawing pictures of themselves, their family, and

peers. These techniques are especially useful when children are unable or

unwilling to express themselves verbally.

Related Topics