Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Child and Adolescent Disorders

Child and Adolescent Disorders

Child and

Adolescent Disorders

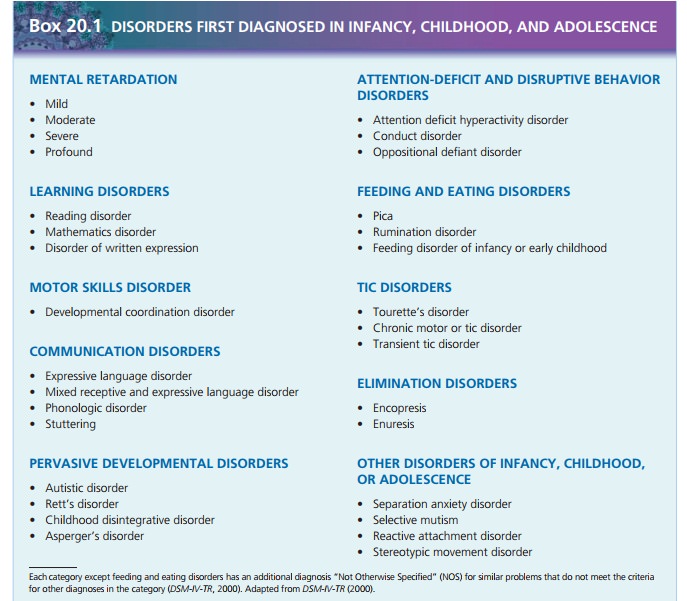

PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS ARE not diagnosed as easily in

children as they are in adults.

Children usually lack the abstract cognitive abilities and verbal skills to

describe what is happening. Because they are constantly changing and

developing, children have limited sense of a stable, normal self to allow them

to discriminate unusual or unwanted symptoms from normal feelings and

sensations. Additionally, behaviors that are normal in a child of one age may

indicate problems in a child of another age. For example, an infant who cries

and wails when separated from his or her mother is normal. If the same child at

5 years of age cries and shows extreme anxiety when separated only briefly from

the mother, however, this behavior would warrant investigation.

Children and adolescents experience some of the same mental health

problems as adults, such as mood and anxiety disorders, and are diagnosed with

these disorders using the same criteria as for adults. Eating disorders,

especially anorexia, usually begin in adolescence and continue into adult-hood.

Mood, anxiety, and eating disorders are discussed in separate chap-ters of this

book.

The childhood psychiatric disorders, most com-mon in mental health

settings and specialized treatment units, include per-vasive developmental

disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and disruptive

behavior disorders.

MENTAL RETARDATION

The essential feature of mental retardation is below-average

intellectual functioning (intelligence quotient [IQ] less than 70) accompanied

by significant limitations in areas of adaptive functioning such as

communication skills, self-care, home living, social or interpersonal skills,

use of community resources, self-direction, academic skills, work, leisure, and

health and safety (King, Hodapp, & Dykens, 2005). The degree of retardation

is based on IQ and greatly affects the person’s ability to function:

·

Mild retardation: IQ 50 to 70

·

Moderate retardation: IQ 35 to 50

·

Severe retardation: IQ 20 to 35

·

Profound retardation: IQ less than 20

Causes of mental retardation include hereditary condi-tions such as

Tay–Sachs disease or fragile X chromosome syndrome; early alterations in

embryonic development, such as trisomy 21 or maternal alcohol intake, that

cause fetal alcohol syndrome; pregnancy or perinatal problems such as fetal

malnutrition, hypoxia, infections, and trauma; medical conditions of infancy

such as infection or lead poisoning; and environmental influences such as

depriva-tion of nurturing or stimulation.

Some people with mental retardation are passive and dependent;

others are aggressive and impulsive. Children with mild-to-moderate mental

retardation usually receive treatment in their homes and communities and make

peri-odic visits to physicians. Those with severe or profound mental

retardation may require residential placement or day care services.

LEARNING DISORDERS

A learning disorder is diagnosed when a child’s achieve-ment in

reading, mathematics, or written expression is below that expected for age,

formal education, and intel-ligence. Learning problems interfere with academic

achievement and life activities requiring reading, math, or writing (American

Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000). Reading and written expression disorders

usually are iden-tified in the first grade; math disorder may go undetected

until the child reaches fifth grade. Approximately 5% of children in U.S.

public schools are diagnosed with a learn-ing disorder. The school dropout rate

for students with learning disorders is 1.5 times higher than the average rate

for all students (APA, 2000).

Low self-esteem and poor social skills are common in children with

learning disorders. As adults, some have prob-lems with employment or social

adjustment; others have minimal difficulties. Early identification of the

learning dis-order, effective intervention, and no coexisting problems is

associated with better outcomes. Children with learning disorders are assisted

with academic achievement through special education classes in public schools.

MOTOR SKILLS DISORDER

The essential feature of developmental

coordination disorder is impaired coordination severe enough to interfere

with academic achievement or activities of daily living (APA, 2000). This

diagnosis is not made if the problem with motor coordination is part of a

general medical condition such as cerebral palsy or muscular dystrophy. This

disor-der becomes evident as a child attempts to crawl or walk or as an older child

tries to dress independently or manip-ulate toys such as building blocks.

Developmental coordi-nation disorder often coexists with a communication

disorder. Its course is variable; sometimes lack of coordi-nation persists into

adulthood (APA, 2000). Schools pro-vide adaptive physical education and sensory

integration programs to treat motor skills disorder. Adaptive physical

education programs emphasize inclusion of movement games such as kicking a

football or soccer ball. Sensory integration programs are specific physical

therapies pre-scribed to target improvement in areas where the child has

difficulties. For example, a child with tactile defensiveness (discomfort at

being touched by another person) might be involved in touching and rubbing skin

surfaces (Pataki & Spence, 2005).

COMMUNICATION DISORDERS

A communication disorder is diagnosed when a communi-cation deficit

is severe enough to hinder development, academic achievement, or activities of

daily living, includ-ing socialization. Expressive

language disorder involves an impaired ability to communicate through

verbal and sign languages. The child has difficulty learning new words and

speaking in complete and correct sentences; his or her speech is limited. Mixed receptive-expressive language disor-der

includes the problems of expressive language disorder along with difficulty understanding (receiving) and deter-mining

the meaning of words and sentences. Both disor-ders can be present at birth

(developmental) or may be acquired as a result of neurologic injury or insult

to the brain. Phonologic disorder

involves problems with articula-tion (forming sounds that are part of speech). Stuttering is a disturbance of the

normal fluency and time patterning of speech. Phonologic disorder and

stuttering run in families and occur more frequently in boys than in girls.

Communication disorders may be mild to severe. Dif-ficulties that

persist into adulthood are related most closely to the severity of the

disorder. Speech and language thera-pists work with children who have

communication disor-ders to improve their communication skills and to teach

parents to continue speech therapy activities at home ( Johnson &

Beitchman, 2005).

PERVASIVE DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDERS

Pervasive developmental

disorders are characterized by pervasive

and usually severe impairment of reciprocal social interaction skills,

communication deviance, and restricted stereotypical behavioral patterns

(Volkmar, Klin,

· Schultz, 2005). This category of disorders is also called autism spectrum disorders and includes autistic disorder (classic autism), Rett’s disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder, and Asperger’s disorder. Approximately 75% of children with pervasive developmental disorders have mental retardation (APA, 2000).

Related Topics