Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Child and Adolescent Disorders

Dementia

DEMENTIA

Dementia is a mental disorder that

involves multiple cog-nitive deficits, primarily memory impairment, and at

least one of the following cognitive disturbances (APA, 2000):

·

Aphasia, which is deterioration of

language function Apraxia, which is

impaired ability to execute motor functions

despite intact motor abilities

·

Agnosia, which is inability to

recognize or name ob-jects despite intact sensory abilities

·

Disturbance in executive

functioning, which is the ability to think abstractly and to plan,

initiate, sequence, monitor, and stop complex behavior

These cognitive deficits must be sufficiently severe to impair

social or occupational functioning and must repre-sent a decline from previous

functioning.

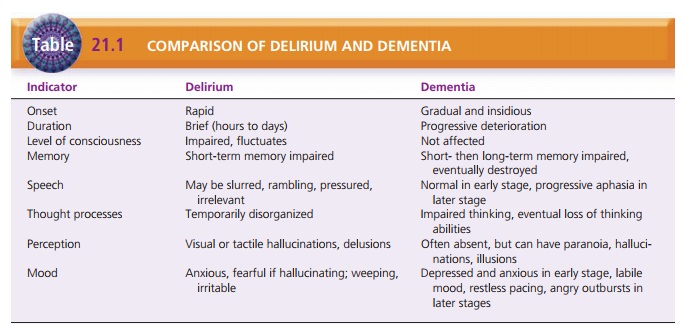

Dementia must be distinguished from delirium; if the two diagnoses

coexist, the symptoms of dementia remain even when the delirium has cleared.

Table 21.1 compares delirium and dementia.

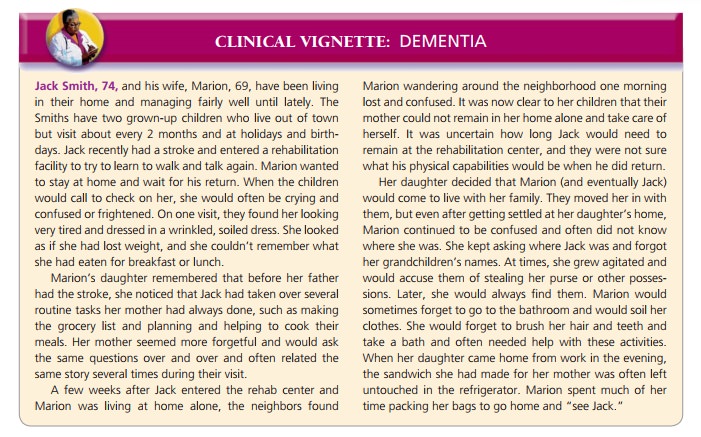

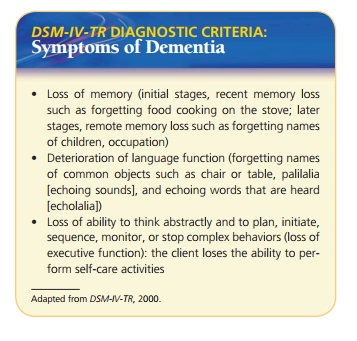

Memory impairment is the prominent early sign of dementia. Clients

have difficulty learning new material and forget previously learned material.

Initially, recent memory is impaired—for example, forgetting where cer-tain

objects were placed or that food is cooking on the stove. In later stages,

dementia affects remote memory; cli-ents forget the names of adult children, their

lifelong occu-pations, and even their names.

Aphasia usually begins with the inability to name familiar objects

or people and then progresses to speech that becomes vague or empty with

excessive use of terms such as it or thing. Clients may exhibit echolalia (echoing what is heard) or palilalia

(repeating words or sounds over and over) (APA, 2000). Apraxia may cause

clients to lose the ability to per-form routine self-care activities such as

dressing or cooking. Agnosia is frustrating for clients: they may look at a

table and chair but are unable to name them. Disturbances in execu-tive

functioning are evident as clients lose the ability to learn new material,

solve problems, or carry out daily activities such as meal planning or

budgeting.

Clients with dementia also may underestimate the risks associated

with activities or overestimate their ability to function in certain

situations. For example, while driving, clients may cut in front of other

drivers, sideswipe parked cars, or fail to slow down when they should.

Onset and Clinical Course

When an underlying, treatable cause is not present, the course of

dementia is usually progressive. Dementia often is described in stages:

·

Mild: Forgetfulness is the hallmark

of beginning, mild de-mentia. It exceeds the normal, occasional forgetfulness

experienced as part of the aging process. The person has difficulty finding

words, frequently loses objects, and be-gins to experience anxiety about these

losses. Occupa-tional and social settings are less enjoyable, and the person

may avoid them. Most people remain in the community during this stage.

·

Moderate: Confusion is apparent, along

with progressive memory loss. The

person no longer can perform com-plex tasks but remains oriented to person and

place. He or she still recognizes familiar people. Toward the end of this

stage, the person loses the ability to live indepen-dently and requires

assistance because of disorientation to time and loss of information such as

address and tele-phone number. The person may remain in the commu-nity if

adequate caregiver support is available, but some people move to supervised

living situations.

·

Severe: Personality and emotional

changes occur. The person may be

delusional, wander at night, forget the names of his or her spouse and

children, and require assistance in activities of daily living (ADLs). Most

peo-ple live in nursing facilities when they reach this stage unless

extraordinary community support is available.

Etiology

Causes vary, although the clinical picture is similar for most

dementias. Often, no definitive diagnosis can be made until completion of a

postmortem examination.

Metabolic activity is decreased in the brains of clients with

dementia; it is not known whether dementia causes decreased metabolic activity

or if decreased metabolic activity results in dementia. A genetic component has

been identified for some dementias such as Huntington’s dis-ease. An abnormal APOE gene is known to be linked with

Alzheimer’s disease. Other causes of dementia are related to infections such as

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. The

most common types of dementia and their known or hypothe-sized causes follow

(APA, 2000; Neugroschl et al., 2005):

·

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive brain disorder

that has a gradual onset but causes

an increasing decline in functioning, including loss of speech, loss of motor

function, and profound personality and behavioral changes such as paranoia,

delusions, hallucinations, in-attention to hygiene, and belligerence. It is

evidenced by atrophy of cerebral neurons, senile plaque deposits, and

enlargement of the third and fourth ventricles of the brain. Risk for

Alzheimer’s disease increases with age, and average duration from onset of

symptoms to death is 8 to 10 years. Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type,

especially with late onset (after 65 years of age), may have a genetic

component. Research has shown link-ages to chromosomes 21, 14, and 19 (APA,

2000).

·

Vascular dementia has symptoms similar to those

of Alzheimer’s disease, but onset is

typically abrupt, fol-lowed by rapid changes in functioning; a plateau, or

leveling-off period; more abrupt changes; another level-ing-off period; and so

on. Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging usually shows multiple

vascular lesions of the cerebral cortex and subcortical structures resulting

from the decreased blood supply to the brain.

·

Pick’s disease is a degenerative brain

disease that par-ticularly affects the frontal and temporal lobes and re-sults

in a clinical picture similar to that of Alzheimer’s disease. Early signs

include personality changes, loss of social skills and inhibitions, emotional

blunting, and language abnormalities. Onset is most commonly 50 to 60 years of

age; death occurs in 2 to 5 years.

·

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease is a central nervous system disorder that typically develops in

adults 40 to 60 years of age. It involves altered vision, loss of coordination

or abnormal movements, and dementia that usually pro-gresses rapidly (a few

months). The cause of the encephalopathy is an infectious particle resistant to

boiling, some disinfectants (e.g., formalin, alcohol), and ultraviolet

radiation. Pressured autoclaving or bleach can inactivate the particle.

·

HIV infection can lead to dementia and other neuro-logic problems;

these may result directly from invasion of nervous tissue by HIV or from other

acquired immu-nodeficiency syndrome–related illnesses such as toxo-plasmosis

and cytomegalovirus. This type of dementia can result in a wide variety of symptoms

ranging from mild sensory impairment to gross memory and cogni-tive deficits to

severe muscle dysfunction.

·

Parkinson’s disease is a slowly progressive

neurologic condition characterized

by tremor, rigidity, bradykine-sia, and postural instability. It results from

loss of neu-rons of the basal ganglia. Dementia has been reported in

approximately 20% to 60% of people with Parkinson’s disease and is

characterized by cognitive and motor slowing, impaired memory, and impaired

executive functioning.

·

Huntington’s disease is an inherited, dominant

gene disease that primarily involves

cerebral atrophy, demy-elination, and enlargement of the brain ventricles.

Ini-tially, there are choreiform movements that are continuous during waking

hours and involve facial contortions, twisting, turning, and tongue movements.

Personality changes are the initial psychosocial mani-festations, followed by

memory loss, decreased intellec-tual functioning, and other signs of dementia.

The disease begins in the late 30s or early 40s and may last 10 to 20 years or

more before death.

·

Dementia can be a direct pathophysiologic consequence of head

trauma. The degree and type of cognitive impairment and behavioral disturbance

depend on the location and extent of the brain injury. When it occurs as a

single injury, the dementia is usually stable rather than progressive. Repeated

head injury (e.g., from box-ing) may lead to progressive dementia.

An estimated 5 million people in the United States have moderate to

severe dementia from various causes. World-wide, it is estimated there are 4.6

million new cases each year (Smith, 2008). Prevalence rises with age: estimated

prevalence of moderate to severe dementia in people older than 65 years is

about 5%; 20% to 40% of the general pop-ulation older than 85 years have

dementia. Predictions are that by 2050, there will be 18 million Americans with

dementia (Neugroschl et al., 2005) and 114 million people with dementia

worldwide (Smith, 2008). Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type is the most common type

in North America (60% of all dementias), Scandinavia, and Europe; vascular

dementia is more prevalent in Russia and Japan. Dementia of the Alzheimer’s

type is more common in women; vascular dementia is more common in men.

Cultural Considerations

Clients from other cultures may find the questions used on many

assessment tools for dementia difficult or impossible to answer. Examples

include the names of former U.S. presidents. To avoid drawing erroneous

conclusions, the nurse must be aware of differences in the person’s knowl-edge

base.

The nurse also must be aware of different culturally influenced

perspectives and beliefs about elderly family

Treatment and Prognosis

Whenever possible, the underlying cause of dementia is identified

so that treatment can be instituted. For example, the progress of vascular

dementia, the second most com-mon type, may be halted with appropriate

treatment of the underlying vascular condition (e.g., changes in diet,

exer-cise, control of hypertension, or diabetes). Improvement of cerebral blood

flow may arrest the progress of vascular dementia in some people (Neugroschl et

al., 2005).

The prognosis for the progressive types of dementia may vary as

described earlier, but all prognoses involve progres-sive deterioration of

physical and mental abilities until death. Typically, in the later stages,

clients have minimal cognitive and motor function, are totally dependent on

caregivers, and are unaware of their surroundings or people in the environment.

They may be totally uncommunicative or make unintelligible sounds or attempts to

verbalize.

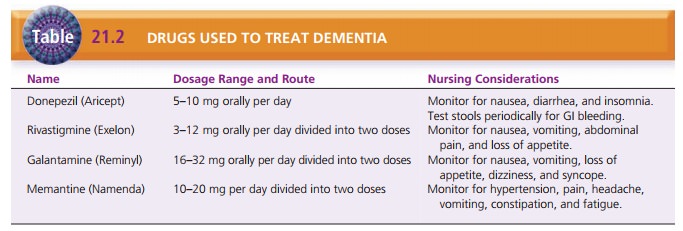

For degenerative dementias, no direct therapies have been found to

reverse or retard the fundamental pathophys-iologic processes. Levels of

numerous neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine, dopamine, norepinephrine, and

serotonin are decreased in dementia. This has led to attempts at replenishment

therapy with acetylcholine precursors, cholinergic agonists, and cholinesterase

inhib-itors. Donepezil (Aricept), rivastigmine (Exelon), and galantamine

(Reminyl) are cholinesterase inhibitors and have shown modest therapeutic

effects and temporarily slow the progress of dementia (Table 21.2). They have

no effect, however, on the overall course of the disease. Tacrine (Cognex) is

also a cholinesterase inhibitor; how-ever, it elevates liver enzymes in about

50% of clients using it. Lab tests to assess liver function are necessary every

1 to 2 weeks; therefore, tacrine is rarely prescribed. Memantine (Namenda) is

an NMDA receptor antagonist that can slow the progression of Alzheimer’s in the

moderate or severe stages (Facts and Comparisons, 2009).

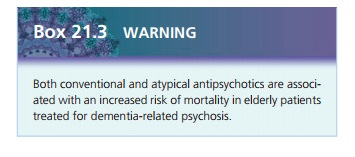

Clients with dementia demonstrate a broad range of behaviors that

can be treated symptomatically. Doses of medications are one half to two thirds

lower than usually prescribed. Antidepressants are effective for significant

depressive symptoms; however, they can cause delirium. SSRI antidepressants are

used since they have fewer side effects. Antipsychotics, such as haloperidol

(Haldol), olan-zapine (Zyprexa), risperidone (Risperdal), and quetiapine

(Seroquel), may be used to manage psychotic symptoms of delusions,

hallucinations, or paranoia, and other behav-iors, such as agitation or

aggression. The potential benefit of antipsychotics must be weighed with the

risks, such as an increased mortality rate, primarily from cardiovascular

complications. Due to this increased risk, the FDA has not approved

antipsychotics for dementia treatment, and there is a black box warning issued.

Lithium carbon-ate, carbamazepine (Tegretol), and valproic acid (Depak-ote)

help to stabilize affective lability and to diminish aggressive outbursts.

Benzodiazepines are used cautiously because they may cause delirium and can

worsen already compromised cognitive abilities (Neugroschl et al., 2005).

Related Topics