Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Neurologic Infections, Autoimmune Disorders, and Neuropathies

Meningitis - Infectious Neurologic Disorders

Infectious Neurologic Disorders

The infectious disorders

of the nervous system include meningitis, brain abscesses, various types of

encephalitis, and CreutzfeldtJakob and new-variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

The clinical manifestations, assessment, and diagnostic findings as well as the

medical and nursing management are related to the specific infectious process.

MENINGITIS

Meningitis is an

inflammation of the meninges, the protective membranes that surround the brain

and spinal cord. Meningitis is classified as aseptic or septic. In aseptic

meningitis, bacteria are not the cause of the inflammation; the cause is viral

or secondary to lymphoma, leukemia, or brain abscess. Septic meningitis refers

to meningitis caused by bacteria, most commonly Neisseria meningitidis, although

Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae are also causative agents.

Outbreaks of N.

meningitidis infection are most likely to occur in dense community groups, such

as college campuses and military installations. Though infections occur year

round, the peak incidence is in the winter and early spring. Factors that

increase the risk for developing bacterial meningitis include tobacco use and

viral upper respiratory infection because they increase the amount of droplet

production. Otitis media and mastoiditis increase the risk of bacterial

meningitis because the bacteria can cross the epithelium membrane and enter the

subarachnoid space. Persons with immune system deficiencies are also at greater

risk for developing bacterial meningitis. Between 1992 and 1996 there was a 28%

increase in the number of new cases reported in the 12-to-29-year-old age group

(Rosenstein, Perkins, Stephens et al.,2001). This increase focused attention on

the need to develop a vaccine for high-risk populations.

Pathophysiology

Meningeal infections

generally originate in one of two ways:through the bloodstream as a consequence

of other infections, or by direct extension, such as might occur after a

traumatic injury to the facial bones, or secondary to invasive procedures.

N. meningitidis

concentrates in the nasopharynx and is transmitted by secretion or aerosol

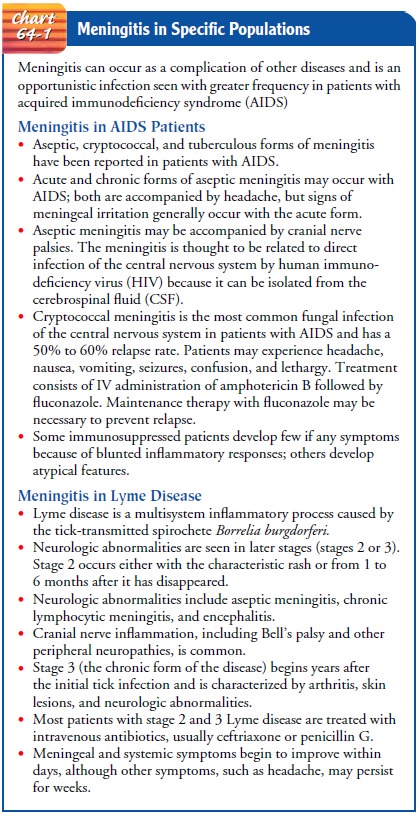

contamination. Bacterial or meningococcal meningitis also occurs as an

opportunistic infection in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

(AIDS) and as a complication of Lyme disease (Chart 64-1). S. pneumoniae is the

most frequent causative agent of bacterial meningitis associated with AIDS

(Rosenstein, Perkins, Stephens et al., 2001).

Once the causative

organism enters the bloodstream, it crosses the blood–brain barrier and causes

an inflammatory reaction in the meninges. Independent of the causative agent,

inflammation of the subarachnoid space and pia mater occurs. Since there is

little room for expansion within the cranial vault, the inflammation may cause

increased intracranial pressure. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flows in the

subarachnoid space, where inflammatory cellular material from the affected

meningeal tissue enters and accumulates in the subarachnoid space, thereby

increasing the CSF cell count (Coyle, 1999).

The prognosis for

bacterial meningitis depends on the causative organism, the severity of the

infection and illness, and the timeliness of treatment. In acute fulminant

presentations there may be adrenal damage, circulatory collapse, and widespread

hemorrhages (Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome). This syndrome is the result of

endothelial damage and vascular necrosis caused by the bacteria. Complications

include visual impairment, deafness, seizures, paralysis, hydrocephalus, and

septic shock.

Clinical Manifestations

Headache and fever are

frequently the initial symptoms. Fever tends to remain high throughout the

course of the illness. The headache is usually severe as a result of meningeal

irritation. Meningeal irritation results in a number of other well-recognized

signs common to all types of meningitis:

·

Nuchal rigidity (stiff neck) is an early sign.

Any attempts at flexion of the head are difficult because of spasms in the

muscles of the neck. Forceful flexion causes severe pain.

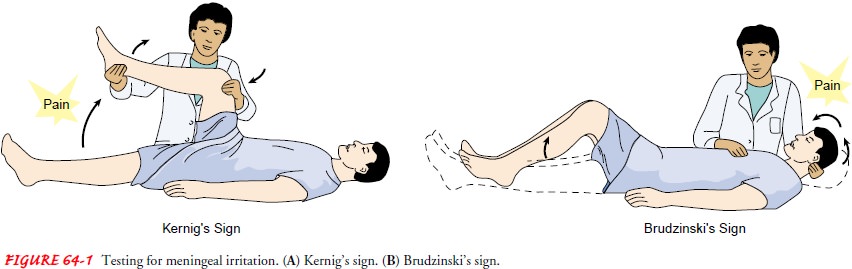

· Positive Kernig’s sign: When the patient is lying with the thigh flexed on the abdomen, the leg cannot be completely extended (Fig. 64-1).

·

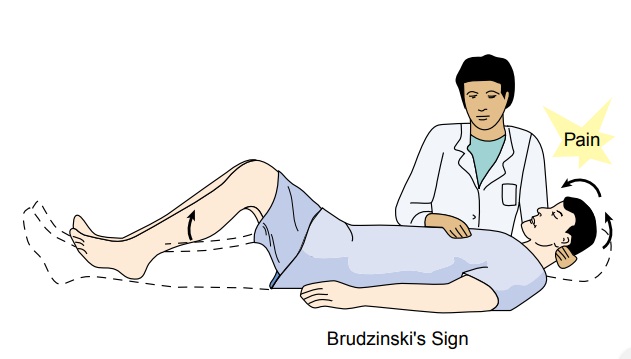

Positive Brudzinski’s sign:

When the patient’s neck is flexed, flexion of the knees and hips is produced;

when passive flex-ion of the lower extremity of one side is made, a similar

movement is seen in the opposite extremity (see Fig. 64-1).

·

Photophobia: extreme

sensitivity to light; this finding is common, although the cause is unclear.

A rash can be a striking feature of N. meningitidis infection, occurring in about half of patients with

this type of meningitis. Skin lesions develop, ranging from a petechial rash

with purpuric lesions to large areas of ecchymosis.

Disorientation and memory impairment are common early in

the course of the illness. The changes depend on the severity of the infection

as well as the individual response to the physiologic processes. Behavioral

manifestations are also common. As the illness progresses, lethargy, unresponsiveness,

and coma may develop.

Seizures and increased intracranial pressure (ICP) are

also as-sociated with meningitis. Seizures occur secondary to focal areas of

cortical irritability. Intracranial pressure increases secondary to

accumulation of purulent exudate. The initial signs of in-creased ICP include

decreased level of consciousness and focal motor deficits. If ICP is not

controlled, the uncus of the temporal lobe may herniate through the tentorium

into the brain stem. Brain stem herniation is a life-threatening event causing

cranial nerve dysfunction and depressing the centers of vital functions, such

as the medulla (Rowland, 2000).

A fulminating infection occurs in about 10% of patients

with meningococcal meningitis, with signs of overwhelming sep-ticemia: an

abrupt onset of high fever, extensive purpuric lesions (over the face and

extremities), shock, and signs of disseminated intravascular coagulopathy

(DIC). Death may occur within a few hours of onset of the infection.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

When the clinical presentation points to meningitis, diagnostic testing to identify the causative organism is conducted. Bacterial culture and Gram staining of CSF and blood are key diagnostic tests (Fischbach, 2002). The presence of polysaccharide antigen in CSF further supports the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis (Rosenstein et al., 2001).

Prevention

In 1971, the military

began vaccinating all new recruits against meningococcal meningitis, resulting

in a dramatic decrease in the incidence. Researchers suggested vaccination of

college freshman as surveillance studies indicated that freshmen living in

dormito-ries were at highest risk for developing meningococcal meningitis. At

this time vaccination is not required for college freshmen; however, the

American Academy of Pediatrics provides informa-tion to college freshmen and

their parents about the risk of dis-ease and the availability of vaccination

(Bruce et al., 2001; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2000).

People in close contact

with patients with meningococcal meningitis should be treated with

antimicrobial chemopro-phylaxis using rifampin (Rifadin), ciprofloxacin

hydrochloride (Cipro), or ceftriaxone sodium (Rocephin) (CDC, 2000). Ther-apy should

be started as soon as possible after contact; a delay in the initiation of

therapy will limit the effectiveness of the pro-phylaxis (Rosenstein et al.,

2001). Vaccination should also be considered as an adjunct to antibiotic

chemoprophylaxis for any-one living with a person who develops meningococcal

infection. Vaccination for children and at-risk adults should be encouraged to

avoid meningitis caused by H. influenzae

and S. pneumoniae.

Medical Management

Successful outcomes depend on the early administration of

an anti-biotic that crosses the blood–brain barrier into the subarachnoid space

in sufficient concentration to halt the multiplication of bac-teria. Penicillin

antibiotics (eg, ampicillin, piperacillin) or one of the cephalosporins (eg,

ceftriaxone sodium, cefotaxime sodium) may be used. Vancomycin hydrochloride

alone or in combina-tion with rifampin may be used if resistant strains of

bacteria are identified. High doses of the appropriate antibiotic are

adminis-tered intravenously.

Dexamethasone has been shown to be beneficial as adjunct

therapy in the treatment of acute bacterial meningitis and in pneumococcal

meningitis if given 15 to 20 minutes before the first dose of antibiotic and

every 6 hours for the next 4 days. Studies indicate that dexamethasone improves

the outcome in adults and does not increase the risk of gastrointestinal

bleeding (de Gans & van de Beek, 2002).

Dehydration and shock are treated with fluid volume

ex-panders. Seizures, which may occur in the early course of the dis-ease, are

controlled with phenytoin (Dilantin). Increased ICP is treated as necessary.

Nursing Management

The patient may be

critically ill; therefore, so many of the nurs-ing interventions are

collaborative with those of the physician, respiratory therapist, and other

members of the health care team. The patient’s prognosis may depend on the

supportive care provided.

Neurologic status and

vital signs are continually assessed. Pulse oximetry and arterial blood gas

values are used to quickly identify the need for respiratory support as the

increasing ICP compromises the brain stem. Insertion of a cuffed endotracheal

tube (or tracheotomy) and mechanical ventilation may be neces-sary to maintain

adequate tissue oxygenation.

Arterial blood pressures

are monitored to assess for incipient shock, which precedes cardiac or

respiratory failure. Rapid intra-venous (IV) fluid replacement may be

prescribed, but care is takento prevent fluid overload. Fever also will

increase the workload of the heart and cerebral metabolism. ICP will increase

in response to increased cerebral metabolic demands. Therefore, measures are

taken to reduce body temperature as quickly as possible.

Other important components of nursing care include:

·

Monitoring body weight, serum

electrolytes, and urine vol-ume, specific gravity, and osmolality, especially

if the syn-drome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) secretion is

suspected

·

Protecting the patient from

injury secondary to seizure ac-tivity or altered level of consciousness

·

Preventing complications

associated with immobility, such as pressure ulcers and pneumonia

·

Instituting droplet

precautions until 24 hours after the ini-tiation of antibiotic therapy (oral

and nasal discharge is con-sidered infectious)

Any sudden, critical illness can be devastating to the

family. Because the patient’s condition is often critical and the progno-sis

guarded, the family needs to be informed about the patient’s condition and

permitted to see the patient at intervals, even though the priority is to

address the patient’s need for immediate and intensive treatment. An important

aspect of the nurse’s role is to support the patient and to assist the family

in identifying others who can be supportive to them during the crisis.

Related Topics