Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Neurologic Infections, Autoimmune Disorders, and Neuropathies

Myasthenia Gravis - Autoimmune Processes

MYASTHENIA GRAVIS

Myasthenia gravis, an autoimmune disorder affecting the

myo-neural junction, is characterized by varying degrees of weakness of the

voluntary muscles. Women tend to develop the disease at an earlier age (20 to

40 years of age) compared to men (60 to 70 years of age), and women are

affected more frequently (Heitmiller, 1999).

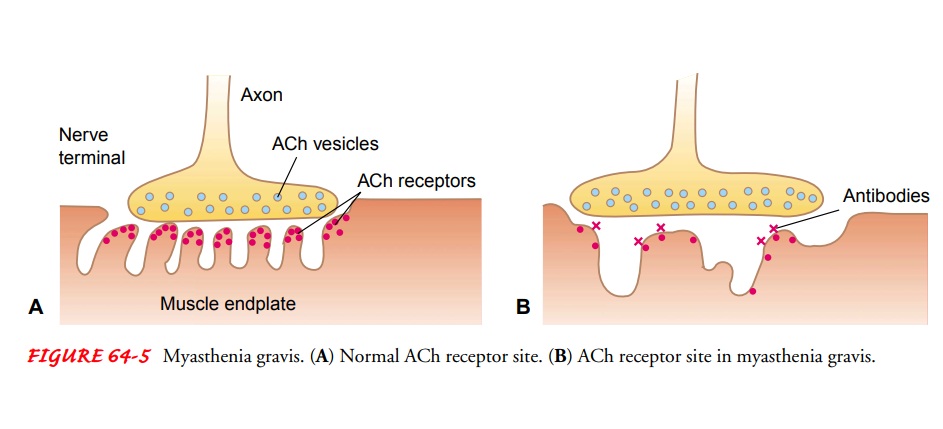

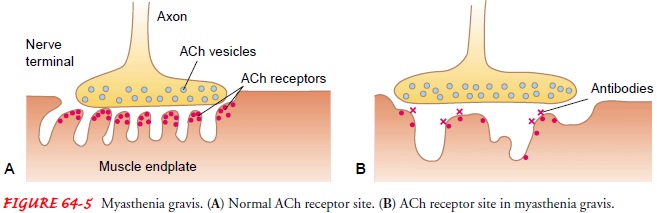

Pathophysiology

Normally, a chemical impulse precipitates the release of

acetyl-choline from vesicles on the nerve terminal at the myoneural junction.

The acetylcholine attaches to receptor sites on the motor end plate,

stimulating muscle contraction. Continuous binding of acetylcholine to the

receptor site is required for muscular con-traction to be sustained.

In myasthenia gravis,

autoantibodies directed at the acetyl-choline receptor sites impair

transmission of impulses across the myoneural junction. Therefore, fewer

receptors are available for stimulation, resulting in voluntary muscle weakness

that escalates with continued activity (Fig. 64-5). These antibodies are found

in 80% to 90% of the people with myasthenia gravis. Eighty per-cent of persons

with myasthenia gravis have either thymic hyper-plasia or a thymic tumor (Roos,

1999), and the thymus gland is believed to be the site of antibody production.

In patients who are antibody negative, it is believed that the offending

antibody is directed at a portion of the receptor site rather than the whole

complex.

Clinical Manifestations

The initial

manifestation of myasthenia gravis usually involves the ocular muscles.

Diplopia (double vision) and ptosis (drooping of the eyelids) are common.

However, the majority of patients also experience weakness of the muscles of

the face and throat (bulbar symptoms) and generalized weakness. Weakness of the

facial muscles will result in a bland facial expression. Laryngeal involvement

produces dysphonia (voice

impairment) and in-creases the patient’s risk for choking and aspiration.

Generalized weakness affects all the extremities and the intercostal muscles,

resulting in decreasing vital capacity and respiratory failure. Myasthenia

gravis is purely a motor disorder with no effect on sensation or coordination.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

An anticholinesterase

test is used to diagnose myasthenia gravis. Anticholinesterase agents stop the

breakdown of acetylcholine, thereby increasing acetylcholine availability.

Edrophonium chlo-ride (Tensilon) is injected intravenously, 2 mg at a time to a

total of 10 mg. Thirty seconds after injection, facial muscle weakness and

ptosis should resolve for about 5 minutes. This immediate improvement in muscle

strength after administration of this agent represents a positive test and

usually confirms the diagnosis. Atropine 0.4 mg should be available to control

the side effects of edrophonium, which include bradycardia, sweating, and

cramping (Roos, 1999).

The acetylcholine receptor antibody titers are elevated as in-dicated previously. Repetitive nerve stimulation tests record the electrical activity in targeted muscles after nerve stimulation. A 15% decrease in successive action potentials is observed in pa-tients with myasthenia gravis (Heitmiller, 1999). The thymus gland, which is a site of acetylcholine receptor antibody produc-tion, is enlarged in myasthenia gravis. MRI demonstrates this en-largement in 90% of cases (Wilkins & Bulkley, 1999).

Medical Management

Management of myasthenia

gravis is directed at improving function and reducing and removing circulating

antibodies. Therapeutic modalities include administration of anticholinesterase

agents and immunosuppressive therapy, plasmapheresis, and thymectomy.

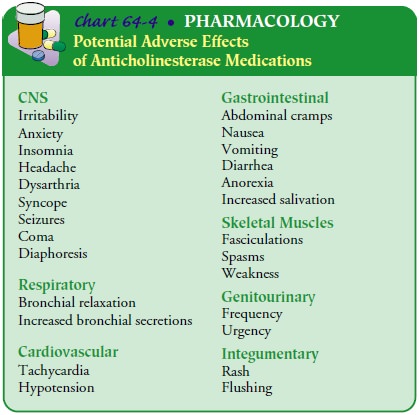

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Anticholinesterase

agents such as pyridostigmine bromide (Mesti-non) and neostigmine bromide

(Prostigmin) provide symptomatic relief by increasing the relative

concentration of available acetyl-choline at the neuromuscular junction. Dosage

is increased grad-ually until maximal benefits (improved strength, less

fatigue) are obtained. Adverse effects of anticholinesterase therapy include

ab-dominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and increased oropharyngeal secre-tions.

Pyridostigmine tends to have fewer side effects (Chart 64-4). Improvement with

anticholinesterase therapy is not complete or long-lasting (Heitmiller, 1999).

The goal of immunosuppressive therapy is to reduce the pro-duction of the antibody. Corticosteroids suppress the patient’s immune response, thus decreasing the amount of antibody pro-duction. As the corticosteroid dosage is gradually increased, the anticholinesterase dosage is lowered. The patient’s ability to main-tain effective respirations and to swallow is monitored through-out. Prednisone, taken on alternate days to lower the incidence of side effects, appears to be successful in suppressing the disease. The patient sometimes shows a marked decrease in muscle strength right after therapy is started, but this is usually only temporary Cytotoxic medications have also been used, although the precise mechanism of action in myasthenia is not fully under-stood.

Medications

such as azathioprine (Imuran), cyclophos-phamide (Cytoxan), and cyclosporine

reduce the circulating anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody titers. Side effects

are significant; therefore, these agents are reserved for patients who do not

re-spond to other forms of therapy.

A number of medications

are contraindicated for patients with myasthenia gravis because they worsen

myasthenic symptoms. Risks and benefits should be weighed by the physician and

the patient before taking any new medications, including antibiotics,

cardiovascular medications, antiseizure and psychotropic med-ications,

morphine, quinine and related agents, beta-blockers, and nonprescription

medications. Procaine (Novocain) should be avoided, and the patient’s dentist

is so advised.

PLASMAPHERESIS

Plasma exchange

(plasmapheresis) is a technique used to treat exacerbations. The patient’s

plasma and plasma components are removed through a centrally placed large-bore

double-lumen catheter. The blood cells and antibody-containing plasma are

sep-arated; then the cells and a plasma substitute are reinfused. Plasma

exchange produces a temporary reduction in the titer of circulat-ing

antibodies. Plasma exchange improves the symptoms in 75% of patients, although

improvement lasts only a few weeks unless plasmapheresis is continued or other

forms of treatment such as immunosuppression with corticosteroids are initiated

(Bedlack & Sanders, 2000). IV immune globulin (IVIG) has recently been

shown to be nearly as effective as plasmapheresis in controlling symptom

exacerbation (Qureshi, Choudhry, Akbar et al., 1999). However, neither therapy

is a cure as it does not stop the pro-duction of the acetylcholine receptor

antibodies.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Thymectomy (surgical removal of the thymus gland) can

produce antigen-specific immunosuppression and result in clinical im-provement.

It can decrease or eliminate the need for medication. In one study 92% of post-thymectomy

patients had symptomatic improvement, with 50% of them no longer requiring

pharmaco-logic therapy (Wilkins & Bulkley, 1999). The entire gland must be

removed for optimal clinical outcomes; therefore, surgeons prefer the

transsternal surgical approach. After surgery, the pa-tient is monitored in an

intensive care unit, with special atten-tion to respiratory function. After the

thymus gland is removed, it may take up to 1 year for the patient to benefit

from the pro-cedure due to the long life of circulating T cells (Wilkins &

Bulkley, 1999).

Complications: Myasthenic Crisis Versus Cholinergic Crisis

A myasthenic crisis is

an exacerbation of the disease process char-acterized by severe generalized

muscle weakness and respiratory and bulbar weakness that may result in

respiratory failure. Crisis may result from disease exacerbation or a specific

precipitating event. The most common precipitator is infection; others include

medication change, surgery, pregnancy, and high environmental temperature (Bella

& Chad, 1998).

Symptoms of

anticholinergic overmedication (cholinergic crisis) may mimic the symptoms of

exacerbation. Differentiation can be achieved with the edrophonium chloride

(Tensilon) test. The patient with myasthenic crisis improves immediately

fol-lowing administration of edrophonium, while the patient with cholinergic

crisis may experience no improvement or deteriorate. If myasthenic crisis is

diagnosed, neostigmine methylsulfate (PMS-Neostigmine, Prostigmin) is

administered intramuscularly or intravenously until the patient is able to

swallow oral anti-cholinesterase medications. Plasmapheresis and IVIG, which

re-duce the antibody load, also may be used to treat myasthenic crisis. If

cholinergic crisis is identified, all anticholinesterase med-ications are

stopped. The patient receives atropine (Atropine sul-fate), the antidote for

the anticholinesterase medications.

Neuromuscular

respiratory failure is the critical complication of crisis. Respiratory muscle

and bulbar weakness combine to cause respiratory compromise. Weak respiratory

muscles will not sup-port inhalation. An inadequate cough and an impaired gag

reflex caused by bulbar weakness result in poor airway clearance. Values on two

respiratory function tests, the negative inspiratory force and vital capacity,

will be the first clinical signs to deteriorate. Careful monitoring of these

values enables the nurse to monitor for impending respiratory failure.

Respiratory support and airway protection are key interventions for the nurse caring

for the pa-tient in crisis. Endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventila-tion

may be needed. Nutritional support may be needed if the patient is intubated

for a long period.

Nursing Management

Because myasthenia gravis is a chronic disease and most

patients are seen on an outpatient basis, much of the nursing care focuses on

patient and family teaching. Educational topics for outpatient self-care

include medication management, energy conservation, strategies to help with

ocular manifestations, and prevention and management of complications.

Medication management is a crucial component of ongoing

care. Understanding the action of the medications and taking them on schedule

is emphasized, as are the consequences of de-laying medication and the signs and

symptoms of myasthenic and cholinergic crisis. The patient can determine the

best times for daily dosing by keeping a diary to determine fluctuation of

symp-toms and to learn when the medication is wearing off. The med-ication

schedule can then be manipulated to maximize strength throughout the day.

The patient is also taught srategies to conserve energy.

To do this, the nurse helps the patient identify the best times for rest

pe-riods throughout the day. If the patient lives in a two-story home, the nurse

can suggest that frequently used items such as hygiene products, cleaning

products, and snacks be kept on each floor to minimize travel between floors.

The patient is encouraged to apply for a handicapped license plate to minimize

walking from parking spaces and to schedule activities to coincide with peak

en-ergy and strength levels.

To minimize the risk of

aspiration, mealtimes should coincide with the peak effects of

anticholinesterase medication. In addition, rest before meals is encouraged to

reduce muscle fatigue. The pa-tient is advised to sit upright during meals with

the neck slightly flexed to facilitate swallowing. Soft foods in gravy or

sauces can be swallowed more easily; if choking occurs frequently, the nurse

can suggest pureéing food to a pudding consistency. Suction should be available

at home and the patient and family instructed in its use. Gastrostomy feedings

may be necessary in some patients to ensure adequate nutrition.

Impaired vision results

from ptosis of one or both eyelids, decreased eye movement, or double vision.

To prevent corneal damage when the eyelids do not close completely, the patient

is instructed to tape the eyes closed for short intervals and regularlyinstill

artificial tears. Patients who wear eyeglasses can have “crutches” attached to

help lift the eyelids. Patching one eye can help with double vision.

The patient is reminded

of the importance of maintaining health promotion practices and of following

health care screen-ing recommendations. Factors that will exacerbate symptoms

and potentially cause crisis should be noted and avoided: emotional stress,

infections (particularly respiratory infections), vigorous physical activity,

some medications, and high environmental temperature. The Myasthenia Gravis

Foundation of America provides support groups, services, and educational

materials for patients, families, and health care providers.

MANAGING MYASTHENIC AND CHOLINERGIC CRISES

Respiratory

distress and varying degrees of dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), dysarthria

(difficulty speaking), eyelid ptosis, diplopia, and prominent muscle weakness

are symptoms of myasthenic and cholinergic crisis. The patient is placed in an

intensive care unit for constant monitoring because of associated intense and

sudden fluctuations in clinical condition.

IV edrophonium chloride

(Tensilon) is used to differentiate the type of crisis. It improves the

condition of the patient in myas-thenic crisis and temporarily worsens that of

the patient in cholin-ergic crisis. If the patient is in true myasthenic

crisis, neostigmine methylsulfate is administered intramuscularly or

intravenously. If the edrophonium test is inconclusive or there is increasing

respi-ratory weakness, all anticholinesterase medications are stopped, and

atropine sulfate is given to reduce excessive secretions.

Providing ventilatory assistance takes precedence in the

im-mediate management of the patient with myasthenic crisis. On-going

assessment for respiratory failure is essential. The nurse assesses the

respiratory rate, depth, and breath sounds and mon-itors pulmonary function

parameters (vital capacity and negative inspiratory force) to detect pulmonary

problems before respira-tory dysfunction progresses. Blood is drawn for

arterial blood gas analysis. Endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation

may be needed.

When there is severe weakness of the abdominal,

intercostal, and pharyngeal muscles, the patient cannot cough, take deep

breaths, or clear secretions. Chest physical therapy, including postural

drainage to mobilize secretions, and suctioning to re-move secretions may have

to be performed frequently. (Postural drainage should not be performed for 30

minutes after feeding.)

Assessment strategies and supportive measures include the

following:

·

Arterial blood gases, serum

electrolytes, input and output, and daily weight are monitored.

·

If the patient cannot swallow,

nasogastric tube feedings may be prescribed.

·

Sedatives and tranquilizers

are avoided because they aggra-vate hypoxia and hypercapnia and can cause

respiratory and cardiac depression.

Related Topics