Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: Skin tumours

Malignant melanoma

Malignant melanoma

Malignant

melanoma attracts a disproportionate amount of attention because it is so often

lethal. The public now knows more about its increasing incidence and dangers.

Incidence

The incidence in white people in the UK and USA is doubling every 10 years. In Scotland and northern parts of the USA the incidence is now about 10 per 100 000 per year, with females being affected more often than males.

There is a higher incidence in white people

living near the equator than in temperate zones and there the female

preponderance is lost. The high-est incidence, more than 40 per 100 000 per

year, is seen in white people living in Australia and New Zealand. The tumour

is rare before puberty and in black people, Asians and Orientals and when it

does occur in these races it is most often on the palms, soles or mucous

membranes.

Cause

Genetic.

Malignant melanomas are most common inwhite people with blond or red hair, many

freckles and a fair skin that tans poorly. Those of Celtic origin are

especially susceptible. Ten to 15% of melanomas are familial (occur in families

where two or more first-degree relatives have a melanoma). Molecular defects in

both tumour suppressor genes and oncogenes have been linked to these melanomas;

the one attracting most interest at present lies on chromosome 9p and encodes a

tumour suppressor gene designated p16, also known as CDKN2A.

Melanoma may affect sev-eral members of a single family in association with

atypical (dysplastic) naevi.

Sunlight.

Both the incidence and mortality increasewith decreasing latitude. Tumours

occur most often, but not exclusively, on exposed skin.

Pre-existing

melanocytic naevi. The risk of develop-ing a

malignant melanoma is highest in those with atypical naevi, congenital

melanocytic naevi or many banal melanocytic naevi. A pre-existing naevus is

seen histologically in about 30% of malignant melanomas.

Clinical features

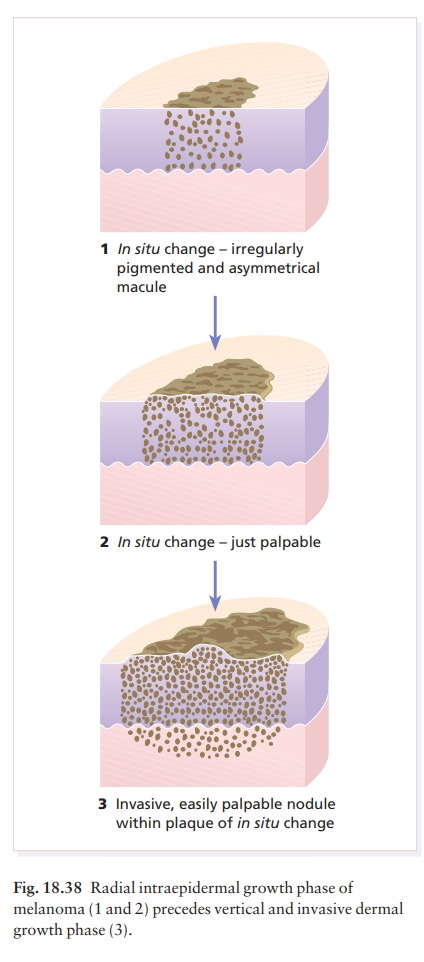

Eighty

per cent of invasive melanomas are preceded by a superficial and radial growth

phase, shown clin-ically as the expansion of an irregularly pigmented macule or

plaque (Fig. 18.38). Most are multicol-oured mixtures of black, brown, blue,

tan and pink. Their margins are irregular with reniform projec-tions and

notches. Malignant cells are at first usually confined to the epidermis and

uppermost dermis, but eventually invade more deeply and may metastasize (Fig.

18.38).

There

are four main types of malignant melanoma.

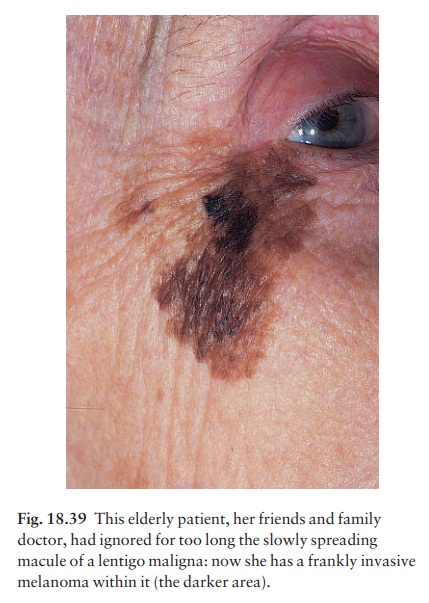

1 Lentigo

maligna melanoma occurs on the exposedskin of the

elderly. An irregularly pigmented, irregu-larly shaped macule (a lentigo

maligna) may have been enlarging slowly for many years as an in situ

melanoma before an invasive nodule (the lentigo maligna melanoma) appears (Fig.

18.39).

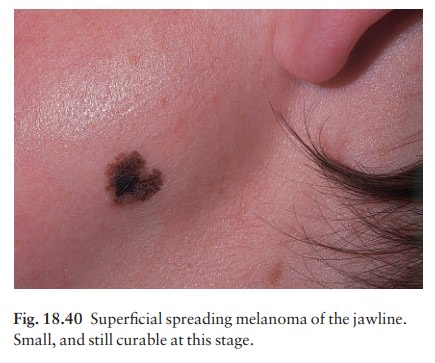

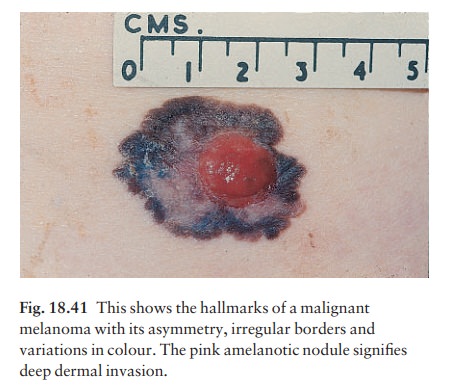

2 Superficial spreading melanomais

the mostcommon type in Caucasoids. Its radial growth phase shows varied colours

and is often palpable (Figs 18.40 and 18.41). A nodule coming up within such a

plaque signifies deep dermal invasion and a poor prognosis (Table 18.4).

3 Acral lentiginous melanomaoccurs

on the palmsand soles and, although rare in Caucasoids, is the most common type

in Chinese and Japanese people. The invasive phase is again signalled by a

nodule coming up within an irregularly pigmented macule or patch.

4 Nodular melanoma(Fig. 18.42) appears as a pig-mented nodule with no preceding in situ phase. It is the most rapidly growing and aggressive type.

Melanomas

can also described by their colour, site and degree of spread.

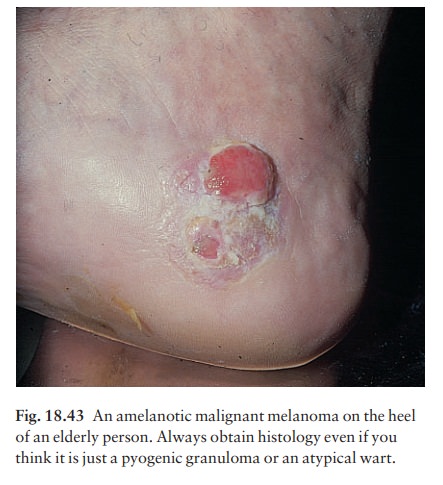

ŌĆó

Totally amelanotic melanomas (Fig.

18.43) are rareand occur especially on the soles of the feet. Flecks of pigment

can usually be seen with a lens.

Subungual melanomas are painless areas of pig-mentation expanding under the nail and onto the nail fold.

ŌĆó

Metastatic melanoma has spread

to surroundingskin, regional lymph nodes or to other organs. At this stage it

can rarely be cured.

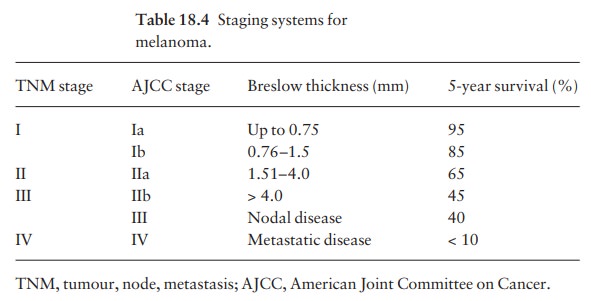

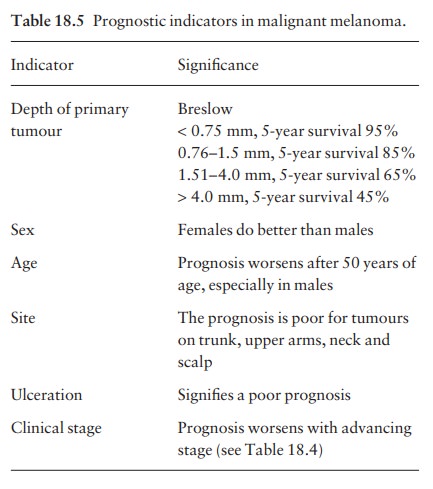

Staging

The most popular staging systems for melanoma are the TNM classification (Europe) and the American

Joint

Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system in the USA (Table 18.4). They provide a

useful guide to prognosis (see also Table 18.5).

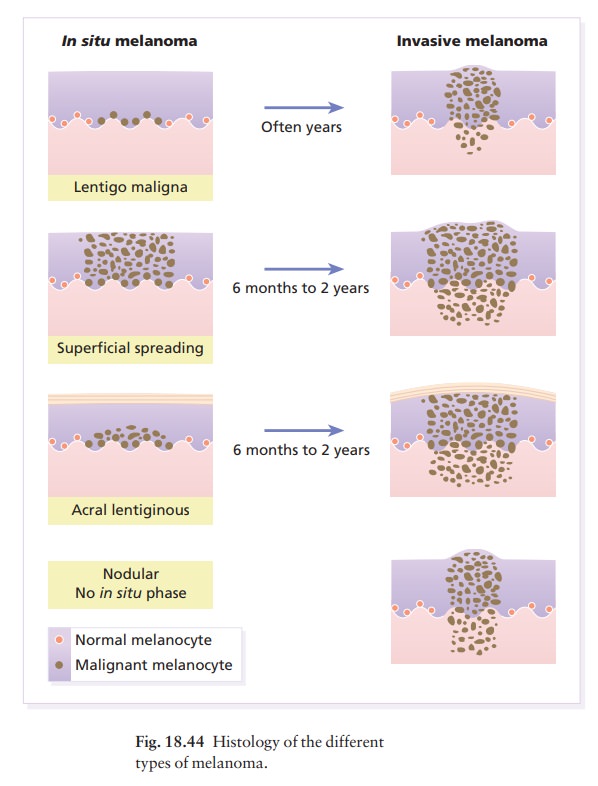

Histology

ŌĆó

Lentigo maligna. Numerous atypical melanocytes,many

in groups, are seen along the basal layer extend-ing downwards in the walls of

hair follicles.

ŌĆó

Lentigo maligna melanoma. Dermal

invasion occurs,with a breach of the basement membrane region. Insitu changes

are seen in the adjacent epidermis.

ŌĆó

Superficial spreading melanoma in situ.

Largeepithelioid melanoma cells permeate the epidermis.

Superficial spreading melanoma. The dermal nodulemay be composed of epithelioid cells, spindle cells or naevus-like cells. In situ changes are seen in the adjac-ent epidermis.

ŌĆó

Acral lentiginous melanoma in situ.

Atypicalmelanocytes are seen in the base of the epidermis and permeating the

mid epidermis.

ŌĆó

Acral lentiginous melanoma. Melanoma

cells invadethe dermis. In situ changes are seen in the adjacent

epidermis.

ŌĆó Nodular melanoma. The tumour comprises epithe-lioid, spindle and naevoid cells and there is no in situ melanoma in the adjacent epidermis.

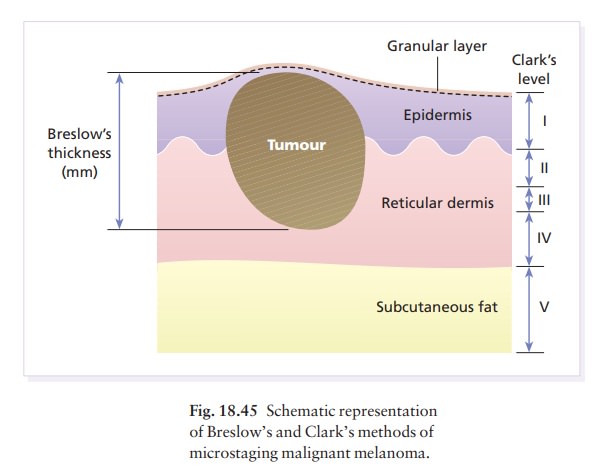

Microstaging

The histology (Fig. 18.44) can be used to assess prog-nosis. BreslowŌĆÖs method is to measure, with an ocular micrometer, the vertical distance from the granular cell layer to the deepest part of the tumour. ClarkŌĆÖs method is to assess the depth of penetration of the melanoma (Fig. 18.45) in relation to the different layers of the dermis. The thicker and more penetrat-ing a lesion, the worse is its prognosis .

Differential diagnosis

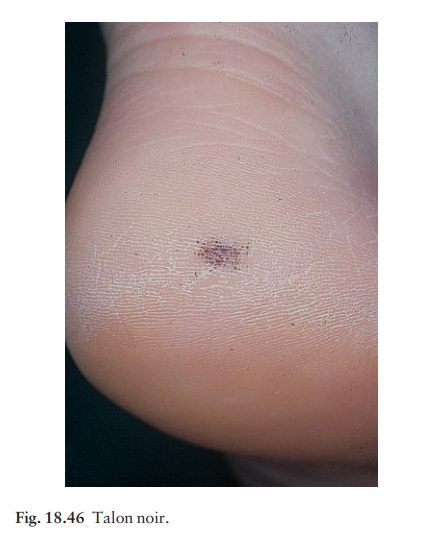

This

includes a melanocytic naevus, seborrhoeic ker-atosis, pigmented actinic

keratosis, pigmented basal cell carcinoma and sclerosing haemangioma;. A malignant

melanoma can also be confused with a subungual or peri-ungual haematoma (see

Fig. 13.21). A history of trauma helps here, as may paring. ŌĆśTalon noirŌĆÖ (Fig.

18.46) is a pigmented petechial area on the heel following minor trauma from

ill-fitting training shoes. An amelanotic melanoma is most often confused with

a pyogenic granuloma and with a squamous cell carcinoma.

Prognosis

The

prognostic indicators, and their significance, are listed in Table 18.5. They

have been established by following up large numbers of patients who have

undergone appropriate surgical treatment .

Treatment

Surgery.

Surgical excision, with minimal delay, isrequired. An excision biopsy, with a

2-mm margin of clearance laterally, and down to the subcutaneous fat, is

recommended for all suspicious lesions. If the histology confirms the diagnosis

of malignant melanoma then wider excision, including the wound

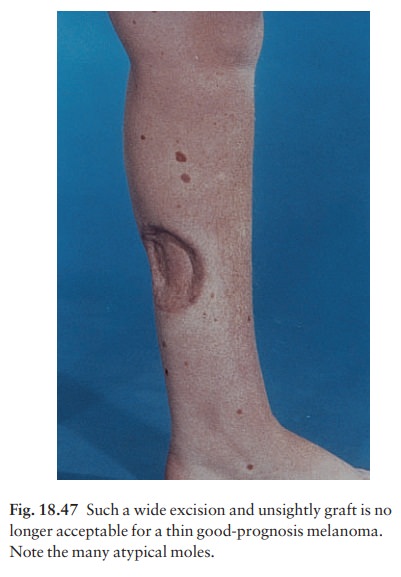

A minimum of 0.5 cm clearance for in situ melanomas and 1 cm clearance is required for all inva-sive melanomas. Nowadays many surgeons excise 1 cm of normal skin around the tumour (or wound) for every millimetre of tumour thickness, up to 3 mm (Fig. 18.47). The maximum clearance is thus 3 cm of normal skin and, depending on the site, primary closureawithout graftingais often possible.

There is no

convincing evidence that excision margins wider than 3 cm confer any greater

survival advantage. Tissue is removed down to, but not including, the deep

fascia.

Elective

regional node dissection may benefit patients with tumours of intermediate

thickness (1.5ŌĆō4.0 mm). The role of sentinel node biopsy in detecting occult

metastases is currently being investigated in patients with melanomas greater

than 1 mm thick, with the aim of carrying out elective dissection of the local

nodes in positive cases, avoiding this significant pro-cedure when the sentinel

node is not involved. The sentinel node, the first and often nearest local node

in the lymphatic drainage of the tumour, is detected by a blue dye and a

radiolabelled colloid injected intrader-mally around the tumour before excision.

The detec-tion of a positive sentinel node does correlate with prognosis but,

as yet, it remains to be shown that patients benefit from subsequent wide

dissection of the nodes in the local basin or other adjuvant treat-ment (e.g. ╬▒-interferon) after a positive sentinel node is found.

Immunological

treatments. Surgery cures most patientswith early melanoma, but its

effect on survival lessens as the disease advances. Many

ongoing trials are investigating the role of immunotherapy (e.g. with

melanoma-specific antigens) as an adjunct to surgery in patients with poor

prognostic (e.g. TNM stages II and III) melanomas. Low dose ╬▒-interferon appears to improve the disease-free survival

time and high-dose regimens may improve overall survival rates. The results of

randomized control studies of adjunct-ive treatment with various melanoma

vaccines are awaited with interest.

Chemotherapy.

Although rarely curative, chemother-apy may be palliative in 25% of patients

with stage III melanoma.

Related Topics