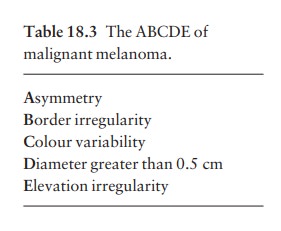

Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: Skin tumours

Benign

Benign

Viral warts

These

are discussed earily, but are mentioned here for two reasons: first, solitary

warts are some-times misdiagnosed on the face or hands of the elderly; and,

secondly, a wart is one of the few tumours in humans that is, without doubt,

caused by a virus. Seventy per cent of transplant patients who have been

immunosuppressed for over 5 years have multiple viral warts and there is

growing evidence that immunosup-pression, viral warts and ultraviolet radiation

interact in this setting to cause squamous cell carcinoma.

Squamous cell papilloma

This common tumour, arising from keratinocytes, may resemble a viral wart clinically. Sometimes an excessive hyperkeratosis produces a horn-shaped excrescence (a ÔÇścutaneous hornÔÇÖ). Excision, or curettage with cautery to the base, is the treatment of choice. The histology should be checked.

Seborrhoeic keratosis (basal cell papilloma, seborrhoeic wart)

This

is a common benign epidermal tumour, unrelated to sebaceous glands. The term

ÔÇśsenile wartÔÇÖ should be avoided as it offends many patients.

Cause

Usually

unexplained but:

ÔÇó

multiple lesions may be inherited

(autosomal dominant);

ÔÇó

occasionally follow an inflammatory

dermatosis; or

ÔÇó

very rarely, the sudden eruption of

hundreds of itchy lesions is associated with an internal neoplasm (LeserÔÇôTr├ęlat

sign).

Presentation

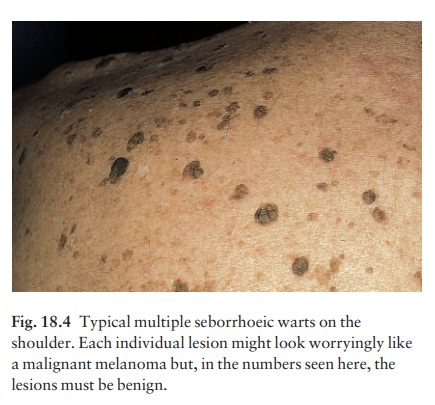

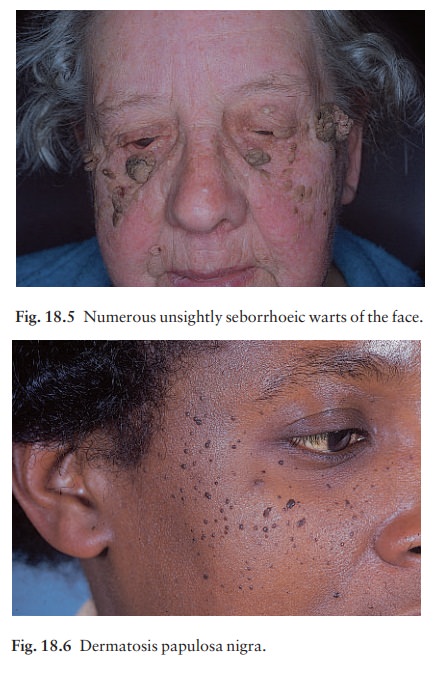

Seborrhoeic

keratoses usually arise after the age of 50 years, but flat inconspicuous

lesions are often visible earlier. They are often multiple (Figs 18.4 and 18.5)

but may be single. Lesions are most common on the face and trunk. The sexes are

equally affected.

Physical

signs:

ÔÇó

a distinctive ÔÇśstuck-onÔÇÖ appearance;

may be flat, raised or pedunculated;

ÔÇó

colour varies from yellow to dark

brown; and

ÔÇó

surface may have greasy scaling and

scattered keratin plugs (ÔÇścurrant bunÔÇÖ appearance).

Clinical course

Lesions

may multiply with age but remain benign.

Differential diagnosis

Seborrhoeic keratoses are easily recognized. Occa-sionally they can be confused with a pigmented cel-lular naevus, a pigmented basal cell carcinoma and, most importantly, with a malignant melanoma. Some Afro-Caribbeans have many dark warty papules on their faces (dermatosis papulosa nigra; Fig. 18.6). Histologically these are like seborrhoeic warts.

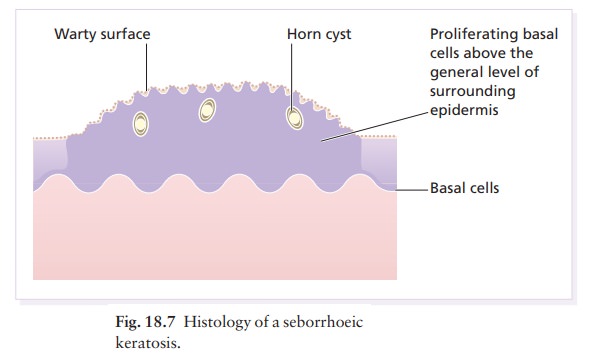

Investigations

Biopsy

is needed only in rare dubious cases. The his-tology is diagnostic (Fig. 18.7):

the lesion lies above the general level of the surrounding epidermis and

consists of proliferating basal cells and horn cysts.

Treatment

Seborrhoeic

keratoses can safely be left alone, but ugly or easily traumatized ones can be

removed with a curette under local anaesthetic (this has the advantage of

providing histology), or by cryotherapy.

Skin tags (acrochordon)

These

common benign outgrowths of skin affect mainly the middle-aged and elderly.

Cause

This

is unknown but the trait is sometimes familial. Skin tags are most common in

obese women, and rarely are associated with tuberous sclerosis, acan-thosis

nigricans or acromegaly, and diabetes.

Presentation and clinical course

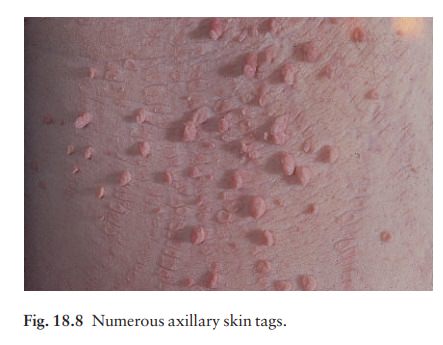

Skin

tags occur around the neck and within the major flexures. They look unsightly

and may catch on clothing and jewellery. They are soft skin-coloured or

pigmented pedunculated papules (Fig. 18.8).

Differential diagnosis

The

appearance is unmistakable. Tags are rarely confused with small melanocytic

naevi.

Treatment

Small lesions can be snipped off with fine scissors, frozen with liquid nitrogen, or destroyed with a hyfre-cator without local anaesthesia. There is no way of preventing new ones from developing.

Linear epidermal naevus

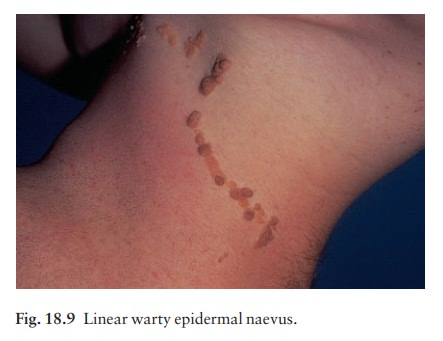

These

lesions are an example of cutaneous mosaicism

and so tend to follow BlaschkoÔÇÖs lines (Fig. 18.9).

Melanocytic naevi

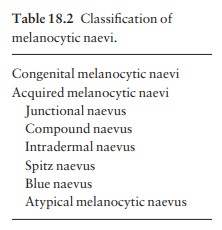

The

term ÔÇśnaevusÔÇÖ refers to a lesion, often present at birth, which has a local

excess of one or more normal constituents of the skin. Melanocytic naevi

(moles) are localized benign proliferations of melanocytes. Their

classification (Table 18.2) is based on the site of the aggregations of naevus

cells (Fig. 18.10).

Cause and evolution

The cause is unknown. A genetic factor is likely in many families, working together with excessive sun exposure during childhood.

With

the exception of congenital melanocytic naevi , most appear in early childhood,

often with a sharp increase in numbers during adolescence. Further crops may

appear during pregnancy, oestro-gen therapy or, rarely, after cytotoxic

chemotherapy and immunosuppression, but new lesions come up less often after

the age of 20 years.

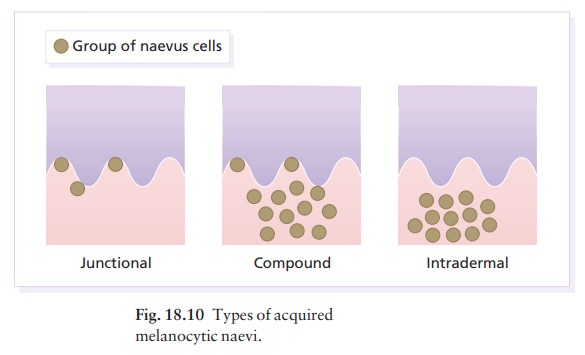

Melanocytic

naevi in childhood are usually of the ÔÇśjunctionalÔÇÖ type, with proliferating

melanocytes in clumps at the dermo-epidermal junction. Later, the melanocytes

round off and ÔÇśdropÔÇÖ into the dermis. A ÔÇścompoundÔÇÖ naevus has both dermal and

junc-tional components. With maturation the junctional component disappears so

that the melanocytes in an ÔÇśintradermalÔÇÖ naevus are all in the dermis (Fig.

18.10).

Presentation

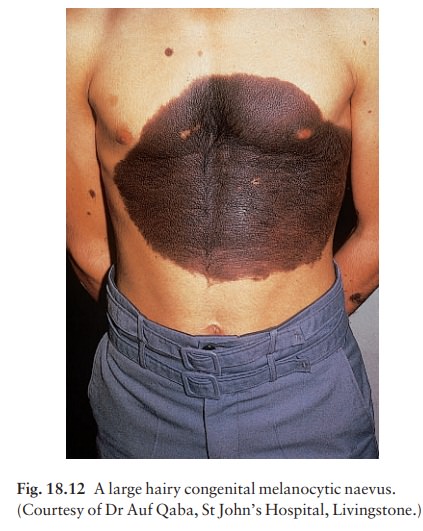

Congenital melanocytic naevi (Figs 18.11 and 18.12).These are present at birth or appear in the neonatal period and are seldom less than 1 cm in diame-ter. Their colour varies from brown to black or blue-black. With maturity some become protuberant and hairy, with a cerebriform surface. Such lesions can be disfiguring, e.g. a ÔÇśbathing trunkÔÇÖ naevus, and carry an increased risk of malignant transformation

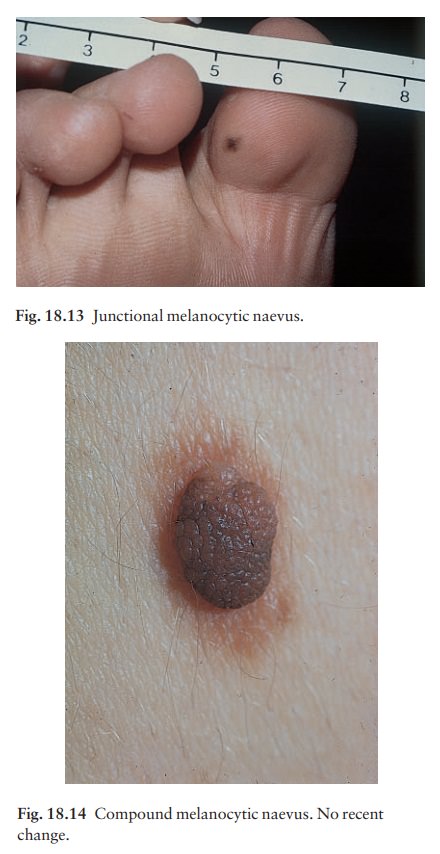

Junctional

melanocytic naevi (Fig. 18.13). These areroughly

circular macules. Their colour ranges from mid to dark brown and may vary even

within a single lesion. Most naevi of the palms, soles and genitals are of this

type.

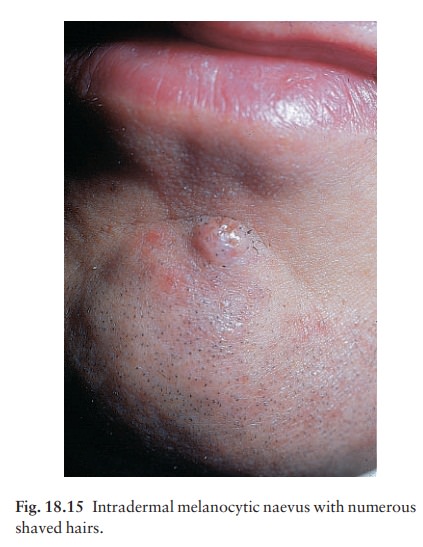

Compound melanocytic naevi (Fig. 18.14). These aredomed pigmented nodules of up to 1 cm in diameter. They may be light or dark brown but their colour is more even than that of junctional naevi. Most are smooth, but larger ones may be cerebriform, or even hyperkeratotic and papillomatous; many bear hairs.

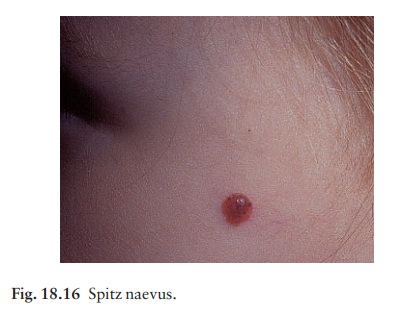

Intradermal

melanocytic naevi (Fig. 18.15). Theselook like

compound naevi but are less pigmented and often skin-coloured.

Spitz

naevi (juvenile melanomas; Fig. 18.16). Theseare usually found in

children. They develop over a month or two as solitary pink or red nodules of

up to 1 cm in diameter and are most common on the face and legs. Although

benign, they are often excised because of their rapid growth.

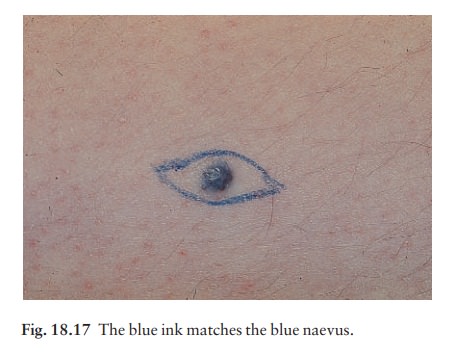

Blue

naevi (Fig. 18.17). So-called because of theirstriking slate

grey-blue colour, blue naevi usually

appear

in childhood and adolescence, on the limbs, buttocks and lower back. They are

usually solitary.

Mongolian

spots. Pigment in dermal melanocytes isresponsible for these

bruise-like greyish areas seen on the lumbosacral area of most DownÔÇÖs syndrome

and many Asian and black babies. They usually fade during childhood.

Atypical mole syndrome (dysplastic naevus syndrome;Fig. 18.18).

Clinically atypical melanocytic naevi can occur

sporadically or run in families as an autosomal dominant trait, with incomplete

penetrance, affecting several generations. Some families with atypical naevi

are melanoma-prone. Genes for susceptibility to melanoma have been mapped to

chromosomes 1p36 and 9p13 in a few of these families. The many large

irregularly pigmented naevi are most obvious on the trunk but some may be

present on the scalp. Their edges are irregular and they vary greatly in

sizeamany being over 1 cm in diameter. Some are pinkish and an inflamed halo

may surround them. Some have a mamillated surface. Patients with multiple

atypical melanocytic or dysplastic naevi with a positive family history of

malignant melanoma should be followed up 6-monthly for life.

Differential diagnosis of melanocytic naevi

ÔÇó

Malignant melanomas. This is

the most importantpart of the differential diagnosis. Melanomas are very rare

before puberty, single and more variably pigmented and irregularly shaped

(other features are listed below under Complications).

ÔÇó

Seborrhoeic keratoses. These

can cause confusionin adults but have a stuck-on appearance and are warty.

Tell-tale keratin plugs and horny cysts may be seen with the help of a lens.

ÔÇó

Lentigines. These may be found on any part of

theskin and mucous membranes. More profuse than junctional naevi, they are

usually grey-brown rather than black, and develop more often after adolescence.

ÔÇó

Ephelides (freckles). These are tan macules

less than

5

mm in diameter. They are confined to sun-exposed areas, being most common in

blond or red-haired people.

ÔÇó

Haemangiomas. Benign proliferations of

bloodvessels, including haemangiomas and pyogenic gran-ulomas, may be confused

with a vascular Spitz naevus or an amelanotic melanoma.

Histology

Most acquired lesions fit into the scheme given in Fig. 18.10: orderly nests of benign naevus cells are seen in the junctional region, in the dermis, or in both. However, some types of melanocytic naevi have their own distinguishing features. In congenital naevi the naevus cells may extend to the subcutaneous fat, and hyperplasia of other skin components (e.g. hair follicles) may be seen.

A Spitz naevus has a histology worry-ingly similar to that of a

melanoma. It shows dermal oedema and dilatated capillaries, and is composed of

large epithelioid and spindle-shaped naevus cells, some of which may be in

mitosis.

In

a blue naevus, naevus cells are seen in the mid and deep dermis.

The

main features of clinically atypical (ÔÇśdysplasticÔÇÖ) naevi are lengthening and

bridging of rete ridges, and the presence of junctional nests showing

melanocytic dysplasia (nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchroma-tism). Fibrosis of

the papillary dermis and a lympho-cytic inflammatory response are also seen.

Complications

ÔÇó

Inflammation. Pain and swelling are common

butare not features of malignant transformation. They are caused by trauma,

bacterial folliculitis or a foreign body reaction to hair after shaving or

plucking.

ÔÇó

Depigmented halo (Fig.

18.19). So-called ÔÇśhalo naeviÔÇÖare uncommon but benign. There may be vitiligo

elsewhere. The naevus in the centre often involutes spontaneously before the

halo repigments.

Malignant change. This is extremely rare exceptin congenital melanocytic naevi, where the risk has been estimated at between 3 and 6% depending on their size (Fig. 18.20), and in the atypical naevi of melanoma-prone families. It should be considered if the following changes occur in a melanocytic naevus

ÔÇó

itch;

ÔÇó

enlargement;

ÔÇó

increased or decreased pigmentation;

ÔÇó

altered shape;

ÔÇó

altered contour;

ÔÇó

inflammation;

ÔÇó

ulceration; or

ÔÇó

bleeding.

If

changing lesions are examined carefully, remember-ing the ÔÇśABCDEÔÇÖ features of

malignant melanoma (Table 18.3), few malignant melanomas should be missed.

Treatment

Excision

is needed when:

1 a

naevus is unsightly;

2 malignancy

is suspected or is a known risk, e.g. in a large congenital melanocytic naevus;

or

3 a naevus is repeatedly inflamed or traumatized.

Epidermoid and pilar cysts

Often

incorrectly called ÔÇśsebaceous cystsÔÇÖ, these are common and can occur on the

scalp, face, behind the ears and on the trunk. They often have a central

punctum; when they rupture, or are squeezed, foul-smelling cheesy material

comes out. Histologically, the lining of a cyst resembles normal epidermis (an

epidermoid cyst) or the outer root sheath of the hair follicle (a pilar cyst).

Occasionally an adjacent foreign body reaction is noted. Treatment is by

excision, or by incision followed by expression of the contents and removal of

the cyst wall.

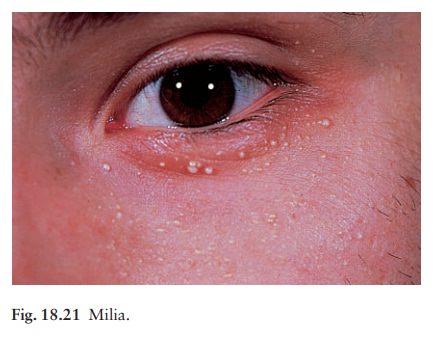

Milia

Milia

are small subepidermal keratin cysts (Fig. 18.21). They are common on the face

in all age groups and appear as tiny white millet seed-like papules of from 0.5

to 2 mm in diameter. They are occasionally seen at the site of a previous

subepidermal blister (e.g. in epidermolysis bullosa and porphyria cutanea

tarda). The contents of milia can be picked out with a sterile needle without

local anaesthesia.

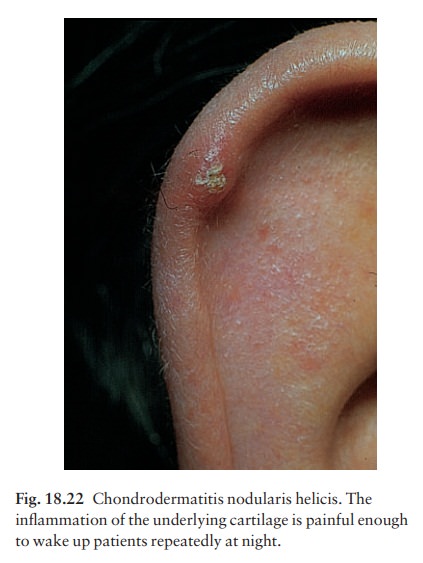

Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis

(painful nodule of the ear, ear corn; Fig. 18.22)

This

terminological mouthful is, strictly, not a neo-plasm, but a chronic

inflammation. A painful nodule develops on the helix or antehelix of the ear,

most often in men. It looks like a small corn, is tender and prevents sleep if

that side of the head touches the pillow. Histologically, a thickened epidermis

overlies inflamed cartilage. Wedge resection under local anaesthetic is

effective if cryotherapy or intralesional triamcinolone injection fails.

Related Topics