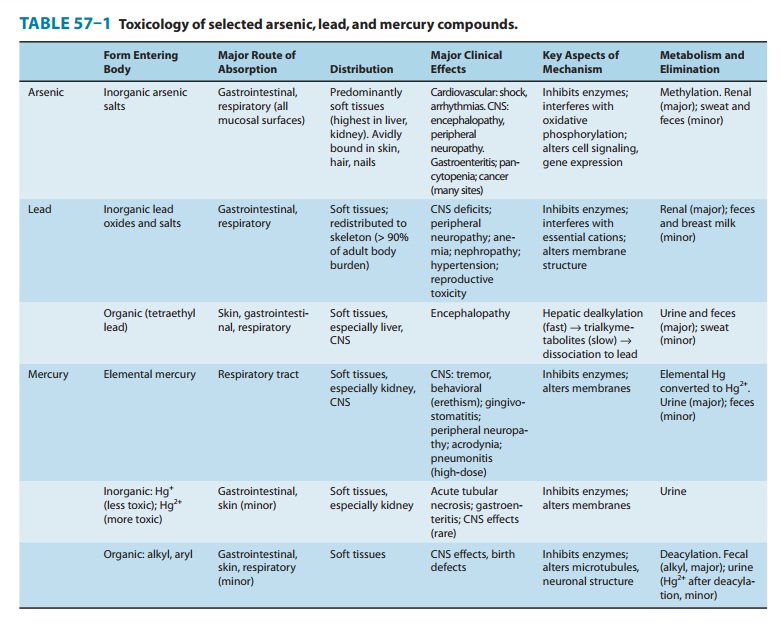

Chapter: Basic & Clinical Pharmacology : Heavy Metal Intoxication & Chelators

Major Forms of Arsenic Intoxication

Major Forms of Arsenic

Intoxication

A. Acute Inorganic Arsenic Poisoning

Within minutes to

hours after exposure to high doses (tens to hundreds of milligrams) of soluble

inorganic arsenic compounds, many systems are affected. Initial

gastrointestinal signs and symp-toms include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and

abdominal pain. Diffuse capillary leak, combined with gastrointestinal fluid

loss, may result in hypotension, shock, and death. Cardiopulmonary toxicity,

including congestive cardiomyopathy, cardiogenic or noncardiogenic pulmonary

edema, and ventricular arrhythmias, may occur promptly or after a delay of

several days. Pancytopenia usually develops within 1 week, and basophilic

stippling of eryth-rocytes may be present soon after. Central nervous system

effects, including delirium, encephalopathy, and coma, may occur within the

first few days of intoxication. An ascending sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy

may begin to develop after a delay of 2–6 weeks. This neuropathy may ultimately

involve the proximal musculature and result in neuromuscular respiratory

failure. Months after an acute poisoning, transverse white striae (Aldrich-Mees

lines) may be visible in the nails.

Acute inorganic

arsenic poisoning should be considered in an individual presenting with abrupt

onset of gastroenteritis in com-bination with hypotension and metabolic

acidosis. Suspicion should be further heightened when these initial findings

are fol-lowed by cardiac dysfunction, pancytopenia, and peripheral neu-ropathy.

The diagnosis may be confirmed by demonstration of elevated amounts of

inorganic arsenic and its metabolites in the urine (typically in the range of

several thousand micrograms in the first 2–3 days after acute symptomatic

poisoning). Arsenic disap-pears rapidly from the blood, and except in anuric

patients, blood arsenic levels should not be used for diagnostic purposes.

Treatment is based on appropriate gut decontamination, intensivesupportive

care, and prompt chelation with unithiol,

3–5 mg/kg intravenously every 4–6 hours, or dimercaprol, 3–5 mg/kg intra-muscularly every 4–6 hours. In animal

studies, the efficacy of chelation has been highest when it is administered

within minutes to hours after arsenic exposure; therefore, if diagnostic

suspi-cion is high, treatment should not be withheld for the several days to

weeks often required to obtain laboratory confirmation.

Succimer

has also been effective in animal models and has a higher therapeutic index

than dimercaprol. However, because it is available in the United States only

for oral administration, its use may not be advisable in the initial treatment

of acute arsenic poi-soning, when severe gastroenteritis and splanchnic edema

may limit absorption by this route.

B. Chronic Inorganic Arsenic Poisoning

Chronic inorganic

arsenic poisoning also results in multisystemic signs and symptoms. Overt

noncarcinogenic effects may be evi-dent after chronic absorption of more than

0.01 mg/kg/d (∼ 500–1000 mcg/d in

adults). The time to appearance of symp-toms varies with dose and

interindividual tolerance. Constitutional symptoms of fatigue, weight loss, and

weakness may be present, along with anemia, nonspecific gastrointestinal

complaints, and a sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy, particularly featuring a

stocking glove pattern of dysesthesia. Skin changes—among the most

characteristic effects—typically develop after years of expo-sure and include a

“raindrop” pattern of hyperpigmentation, and hyperkeratoses involving the hands

and feet (Figure 57–1). Peripheral vascular disease and noncirrhotic portal

hypertension may also occur. Epidemiologic studies suggest a possible link to

hypertension, diabetes, chronic nonmalignant respiratory disease, and adverse

reproductive outcomes. Cancer of the lung, skin, bladder, and possibly other

sites, may appear years after exposure to doses of arsenic that are not high

enough to elicit other acute or chronic effects.

Administration

of arsenite in cancer chemotherapy regimens, often at a daily dose of 10–20 mg

for weeks to a few months, has been associated with prolongation of the QT

interval on the elec-trocardiogram and occasionally has resulted in malignant

ventric-ular arrhythmias such as torsades de pointes.

The diagnosis of chronic arsenic poisoning involves inte-gration of the clinical findings with confirmation of exposure. The urine concentration of the sum of inorganic arsenic and its primary metabolites MMA and DMA is less than 20 mcg/L in the general population. High urine levels associated with overt adverse effects may return to normal within days to weeks after exposure ceases. Because it may contain large amounts of nontoxic organoarsenic, all seafood should be avoided for at least 3 days before submission of a urine sample for diagnostic purposes. The arsenic content of hair and nails (normally less than 1 ppm) may sometimes reveal past elevated exposure, but results should be interpreted cautiously in view of the potential for external contamination.

Management of chronic arsenic poisoning consists primarily of termination of exposure and nonspecific supportive care. Although empiric

short-term oral chelation with unithiol

or succimer for symptomatic

individuals with elevated urine arsenic concentra-tions may be considered, it

has no proven benefit beyond removal from exposure alone. Preliminary studies

suggest that dietary supplementation of folate—thought to be a cofactor in

arsenic methylation—might be of value in arsenic-exposed individuals,

particularly men, who are also deficient in folate.

C. Arsine Gas Poisoning

Arsine gas poisoning

produces a distinctive pattern of intoxication dominated by profound hemolytic

effects. After a latent period that may range from 2 hours to 24 hours

postinhalation (depend-ing on the magnitude of exposure), massive intravascular

hemoly-sis may occur. Initial symptoms may include malaise, headache, dyspnea,

weakness, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, jaundice, and hemoglobinuria.

Oliguric renal failure, a consequence of hemoglobin deposition in the renal

tubules, often appears within 1–3 days. In massive exposures, lethal effects on

cellular respira-tion may occur before renal failure develops. Urinary arsenic

levels are elevated but are seldom available to confirm the diagnosis dur-ing

the critical period of illness. Intensive supportive care— including exchange

transfusion, vigorous hydration, and, in the case of acute renal failure,

hemodialysis—is the mainstay of therapy.Currently available chelating agents

have not been demonstrated to be of clinical value in arsine poisoning.

Related Topics