Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Endocrine Disorders

Hyperthyroidism - Management of Patients With Thyroid Disorders

HYPERTHYROIDISM

Hyperthyroidism

is the second most prevalent endocrine disor-der, after diabetes mellitus. Graves’ disease, the most common type

of hyperthyroidism, results from an excessive output of thy-roid hormones

caused by abnormal stimulation of the thyroid gland by circulating

immunoglobulins. It affects women eight times more frequently than men, with

onset usually between the second and fourth decades (Tierney et al., 2001). It

may appear after an emotional shock, stress, or an infection, but the exact

sig-nificance of these relationships is not understood. Other common causes of

hyperthyroidism include thyroiditis and excessive in-gestion of thyroid

hormone.

Clinical Manifestations

Patients

with well-developed hyperthyroidism exhibit a charac-teristic group of signs

and symptoms (sometimes referred to as thyrotoxicosis).

The presenting symptom is often nervousness.These patients are often

emotionally hyperexcitable, irritable, and apprehensive; they cannot sit

quietly; they suffer from pal-pitations; and their pulse is abnormally rapid at

rest as well as on exertion. They tolerate heat poorly and perspire unusually

freely. The skin is flushed continuously, with a characteristic salmon color,

and is likely to be warm, soft, and moist. Elderly patients, however, may

report dry skin and diffuse pruritus. A fine tremor of the hands may be

observed. Patients may exhibit exophthalmos

(bulging eyes), which produces a startled facialexpression.

Other

manifestations include an increased appetite and di-etary intake, progressive

weight loss, abnormal muscular fatiga-bility and weakness (difficulty in

climbing stairs and rising from a chair), amenorrhea, and changes in bowel

function. The pulse rate ranges constantly between 90 and 160 beats/min; the

sys-tolic, but characteristically not the diastolic, blood pressure is

elevated; atrial fibrillation may occur; and cardiac decompen-sation in the

form of heart failure is common, especially in el-derly patients. Osteoporosis

and fracture are also associated with hyperthyroidism.

Cardiac

effects may include sinus tachycardia or dysrhyth-mias, increased pulse

pressure, and palpitations; it has been sug-gested that these changes may be related

to increased sensitivity to catecholamines or to changes in neurotransmitter

turnover. Myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure may occur if the

hyper-thyroidism is severe and untreated.

The

course of the disease may be mild, characterized by re-missions and

exacerbations and terminating with spontaneous re-covery in a few months or

years. Conversely, it may progress relentlessly, with the untreated person

becoming emaciated, in-tensely nervous, delirious, and even disoriented;

eventually, the heart fails.

Symptoms

of hyperthyroidism may occur with the release of excessive amounts of thyroid

hormone as a result of inflamma-tion after irradiation of the thyroid or

destruction of thyroid tis-sue by tumor. Such symptoms may also occur with

excessive administration of thyroid hormone for treatment of hypothy-roidism.

Long-standing use of thyroid hormone in the absence of close monitoring may be

a cause of symptoms of hyperthy-roidism. It is also likely to result in

premature osteoporosis, par-ticularly in women.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

The thyroid gland invariably is enlarged to

some extent. It is soft and may pulsate; a thrill often can be palpated, and a

bruit is heard over the thyroid arteries. These are signs of greatly in-creased

blood flow through the thyroid gland. In advanced cases, the diagnosis is made

on the basis of the symptoms and an in-crease in serum T4 and an

increased 123I or 125I uptake by the thy-roid in excess

of 50%.

Gerontologic Considerations

Although

hyperthyroidism is much less common in elderly peo-ple than hypothyroidism,

patients older than 60 years account for 10% to 15% of the cases of

thyrotoxicosis. Although some older patients develop typical signs and symptoms

of thyrotoxicosis, in most an atypical picture is present, which is often

subclinical (Toft, 2001).

Elderly

patients commonly present with vague and nonspecific signs and symptoms, making

disorders hard to detect. Symptoms such as tachycardia, fatigue, mental

confusion, weight loss, change in bowel habits, and depression can be

attributed to age and other illnesses common to elderly people. In addition,

the patient may report cardiovascular symptoms and difficulty climbing stairs

or rising from a chair because of muscle weakness. New or worsen-ing heart failure

or angina is more likely to occur in elderly than in younger patients. The

elderly patient may experience a single man-ifestation, such as atrial

fibrillation, anorexia, or weight loss. These signs and symptoms may mask the

underlying thyroid disease.

Spontaneous

remission of hyperthyroidism is rare in elderly patients. Measurement of TSH is

indicated in elderly patients with unexplained physical or mental

deterioration.

Medical Management

Treatment

of hyperthyroidism is directed toward reducing thy-roid hyperactivity to

relieve symptoms and remove the cause of important complications. Treatment

depends on the cause of the hyperthyroidism and may require a combination of

therapeutic approaches.

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Two

forms of pharmacotherapy are available for treating hyper-thyroidism and

controlling excessive thyroid activity: (1) use of irradiation by

administration of the radioisotope 123I or 131I for destructive effects on the thyroid

gland and (2) antithyroid med-ications that interfere with the synthesis of

thyroid hormones and other agents that control manifestations of

hyperthyroidism. Sur-gical removal of most of the thyroid gland is a

nonpharmacologic alternative.

Radioactive Iodine Therapy.

The goal of radioactive iodine ther-apy

(123I or 131I) is to destroy the overactive thyroid

cells. Use of radioactive iodine is the most common treatment in elderly

pa-tients. Almost all the iodine that enters and is retained in the body

becomes concentrated in the thyroid gland. Therefore, the radio-active isotope

of iodine is concentrated in the thyroid gland, where it destroys thyroid cells

without jeopardizing other radiosensitive tissues. Over a period of several

weeks, thyroid cells exposed to the radioactive iodine are destroyed, resulting

in reduction of the hyperthyroid state and inevitably hypothyroidism.

The

patient is instructed about what to expect with this taste-less, colorless

radioiodine, which may be administered by the radi-ologist. A single oral dose

of the agent is administered, based on 80 to 160 ÎĽCi/g estimated thyroid

weight. About 70% to 85% of pa-tients are cured by one dose of radioactive

iodine. An additional 10% to 20% require two doses; rarely is a third dose

necessary. Use of an ablative dose of radioactive iodine initially causes an

acute re-lease of thyroid hormone from the thyroid gland and may cause an

increase of symptoms. The patient is observed for signs of thyroidstorm; propranolol is useful in controlling these symptoms.

After

treatment with radioactive iodine, the patient is followed closely until the

euthyroid state is reached. In 3 to 4 weeks, symptoms of hyperthyroidism

subside. Because the incidence of hypo-thyroidism after this form of treatment

is very high (ie, more than 90% at 10 years), close follow-up is required to

evaluate thyroid function. Thyroid hormone replacement is necessary; small

doses are usually prescribed, with the dose gradually increased over a period

of months (up to about 1 year) until the FT4 and TSH lev-els stabilize within normal ranges.

Radioactive

iodine has been used to treat toxic adenomas and multinodular goiter and most

varieties of thyrotoxicosis (rarely per-manently successful); it is preferred

for treating patients beyond the childbearing years with diffuse toxic goiter.

It is contraindicated in pregnancy and in nursing mothers because radioiodine

crosses the placenta and is secreted in breast milk. A major advantage of

treat-ment with radioactive iodine is that it avoids many of the side ef-fects

associated with antithyroid medications. However, many patients and their

families fear medications that are radioactive. Be-cause of this fear, many

patients elect to take antithyroid medica-tions rather than radioactive iodine.

Gerontologic Considerations

The

use of radioactive iodine is generally recommended for treatment of

thyrotoxicosis in elderly patients unless an enlarged thyroid gland is pressing

on the airway. The hypermetabolic state of thyrotoxicosis must be controlled by

antithyroid medications before radioactive iodine is administered because

radiation may precipitate thyroid storm by increasing the release of hormone

from the thyroid gland. Thyroid storm, if it occurs, has a mortal-ity rate of

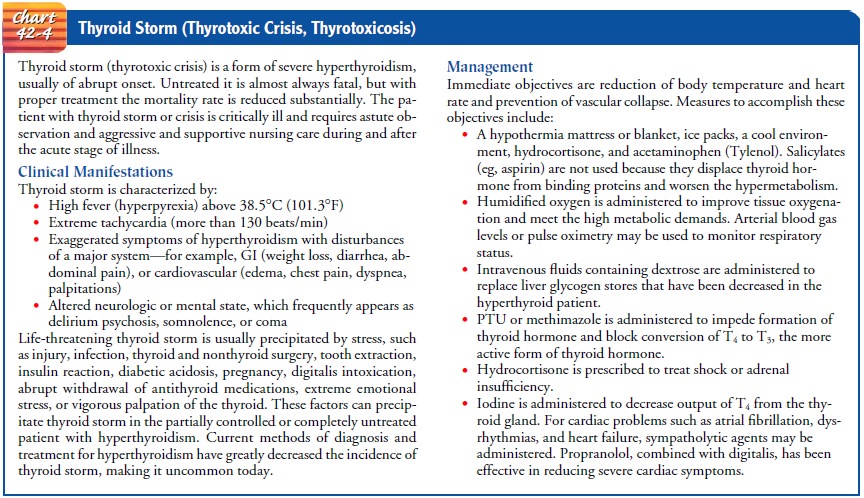

10% in elderly patients (Chart 42-4).

Antithyroid Medications.

The

objective of pharmacotherapy is toinhibit one or more stages in thyroid hormone

synthesis or hor-mone release; another goal may be to reduce the amount of

thy-roid tissue, with resulting decreased thyroid hormone production.

Antithyroid

agents block the utilization of iodine by inter-fering with the iodination of

thyrosine and the coupling of iodothyrosines in the synthesis of thyroid

hormones. This pre-vents the synthesis of thyroid hormone. The most commonly

used medications are propylthiouracil (Propacil, PTU) or me-thimazole

(Tapazole) until the patient is euthyroid (ie, neither hyperthyroid nor

hypothyroid). These medications block ex-trathyroidal conversion of T4 to T3. Because antithyroid

med-ications do not interfere with release or activity of previously formed

thyroid hormones, it may take several weeks for relief of symptoms. At this

time the maintenance dose is established, fol-lowed by a gradual withdrawal of

the medication over the next several months.

Therapy

is determined on the basis of clinical criteria, includ-ing changes in pulse

rate, pulse pressure, body weight, size of the goiter, and results of

laboratory studies of thyroid function.

Toxic

complications of antithyroid medications are relatively uncommon; nevertheless,

the importance of periodic follow-up is emphasized because medication

sensitization, fever, rash, urti-caria, or even agranulocytosis and

thrombocytopenia (decrease in granulocytes and platelets) may develop. With any

sign of infec-tion, especially pharyngitis and fever or the occurrence of mouth

ulcers, the patient is advised to stop the medication, notify the physician

immediately, and undergo hematologic studies. Rash, arthralgias, and fever

occur in 5% of patients. Agranulocytosis, the most serious toxic side effect,

occurs in 1 of every 200 pa-tients. Its incidence is higher in patients older

than 40 years. It generally occurs within the first 3 months of therapy but may

occur up to 1 year after it is started.

Patients

taking antithyroid medications are instructed not to use decongestants for

nasal stuffiness because they are poorly tol-erated. Antithyroid medications

are contraindicated in late preg-nancy because they may produce goiter and

cretinism in the fetus.

Thyroid

hormone is occasionally administered with antithyroid medications to put the

thyroid gland at rest. In this approach, hypothyroidism from excess antithyroid

medication is avoided, as is stimulation of the thyroid gland by TSH. Thyroid

hormone is available as thyroglobulin (Proloid) and levothyroxine sodium

(Synthroid). These slow-acting preparations take about 10 days to achieve their

full effect. Liothyronine sodium (Cytomel) has a more rapid onset, and its

action is of short duration.

Gerontologic Considerations

If

antithyroid agents are used in elderly patients, the patient must be monitored

closely because elderly patients are more likely to de-velop granulocytopenia.

The dosage of other medications to treat other chronic illnesses in elderly

patients may need to be modified because of the altered rate of metabolism in

hyperthyroidism.

Adjunctive Therapy.

Iodine or

iodide compounds, once the onlytherapy available for patients with

hyperthyroidism, are no longer used as the sole method of treatment. Such

compounds decrease the release of thyroid hormones from the thyroid gland and

reduce the vascularity and size of the thyroid. Compounds such as potas-sium

iodide (KI), Lugol’s solution, and saturated solution of potas-sium iodide

(SSKI) may be used in combination with antithyroid agents or beta-adrenergic

blockers to prepare the patient with hyper-thyroidism for surgery. These agents

reduce the activity of the thy-roid hormone and the vascularity of the thyroid

gland, making the surgical procedure safer. Solutions of iodine and iodide

compounds are more palatable in milk or fruit juice and are administered

through a straw to prevent staining of the teeth. These compoundsreduce the metabolic

rate more rapidly than antithyroid medica-tions, but their action does not last

as long.

Beta-adrenergic blocking agents are important

in controlling the sympathetic nervous system effects of hyperthyroidism. For

example, propranolol (Inderal) is used to control nervousness, tachycardia,

tremor, anxiety, and heat intolerance. The patient continues taking propranolol

until the FT4

is within the normal range and the TSH level approaches normal.

Gerontologic Considerations

Use of

beta-adrenergic blocking agents (eg, propranolol [Inderal]) may be indicated to

decrease the cardiovascular and neurologic signs and symptoms of

thyrotoxicosis. These agents must be used with extreme caution in elderly

patients to minimize adverse effects on cardiac function that may produce heart

failure.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgery to remove thyroid tissue was once the

primary method of treating hyperthyroidism; today, surgery is reserved for

spe-cial circumstances—for example, in pregnant women allergic to antithyroid

medications, patients with large goiters, or patients unable to take

antithyroid agents. Surgery for treatment of hyper-thyroidism is performed soon

after the thyroid function has re-turned to normal (4 to 6 weeks).

The

surgical removal of about five sixths of the thyroid tissue (subtotal

thyroidectomy) practically ensures a prolonged remis-sion in most patients with

exophthalmic goiter. Its use today is reserved for large goiters, presence of

obstructive symptoms, preg-nant women, or when there is a need for rapid

normalization of thyroid function (Argueta & Whitaker, 2000; Fatourechi,

2000). Before surgery, propylthiouracil is administered until signs of

hyperthyroidism have disappeared. A beta-adrenergic blocking agent

(propranolol) may be used to reduce the heart rate and other signs and symptoms

of hyperthyroidism; however, this does not create a euthyroid state. Iodine

(Lugol’s solution or potassium io-dide) may be prescribed in an effort to

reduce blood loss; however, the effectiveness of this is unknown. Patients

receiving iodine medication must be monitored for evidence of iodine toxicity

(iodism), which requires immediate withdrawal of the medication. Symptoms of

iodism include swelling of the buccal mucosa, ex-cessive salivation, coryza,

and skin eruptions.

Recurrent Hyperthyroidism

No

treatment for thyrotoxicosis is without side effects, and all three treatments

(radioactive iodine therapy, antithyroid med-ications, and surgery) share the

same complications: relapse or recurrent hyperthyroidism and permanent

hypothyroidism. The rate of relapse increases in patients who had very severe

disease, a long history of dysfunction, ocular and cardiac symptoms, large

goiter, and relapse after previous treatment. The relapse rate after

radioactive iodine therapy depends on the dose used in treatment. Patients

receiving a lower dose of radioactive iodine are more likely to require

subsequent treatment than those being treated with a higher dose.

Hypothyroidism occurs in almost 80% of pa-tients at 1 year and in 90% to 100%

by 5 years for both the mul-tiple low-dose and single high-dose methods.

Although

rates of relapse and the occurrence of hypothy-roidism vary, relapse with

antithyroid medications is about 45% by 1 year after completion of therapy and

almost 75% by 5 years later (Larson et al., 2000). Discontinuation of

antithyroid med-ications before therapy is complete usually results in relapse

within 6 months in most patients. The incidence of relapse with subtotal

thyroidectomy is 19% at 18 months; an incidence of hypothy-roidism of 25% has

been reported at 18 months after surgery. The risk for these complications

illustrates the importance of long-term follow-up of patients treated for

hyperthyroidism.

Related Topics