Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Hearing and Balance Disorders

Hearing Loss

Hearing Loss

More

than 26 million people in the United States have some form of hearing

impairment (Larson et. al., 2000). Most can be helped with medical or surgical

therapies or with a hearing aid. By the year 2050, about one of every five

people in the United States, or almost 58 million people, will be 55 years of

age or older. Of this population, almost one half can expect a hearing

impairment (U.S. Public Health Service, 2000).

Approximately 10 million persons in the United

States have irreversible hearing loss (National Strategic Research Plan of the

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Dis-orders [NIDCD],

1998). It is estimated that more than 30 mil-lion people are exposed to noise

levels that produce hearing loss on a daily basis. Occupations such as

carpentry, plumbing, and coal mining have the highest risk of noise-induced

hearing loss. Researchers report greater than 90% of coal miners are estimated

to have hearing loss by the age of 52 years (Franks, 1996).

Conductive

hearing loss usually results from an external ear disorder, such as impacted

cerumen, or a middle ear disorder, such as otitis media or otosclerosis. In

such instances, the effi-cient transmission of sound by air to the inner ear is

interrupted. A sensorineural loss involves damage to the cochlea or

vestibu-locochlear nerve.

Mixed

hearing loss and functional hearing loss also may occur. The patient with mixed

hearing loss has conductive loss and sensorineural loss, resulting from

dysfunction of air and bone conduction. A functional (or psychogenic) hearing

loss is nonorganic and unrelated to detectable structural changes in the

hearing mechanisms; it is usually a manifestation of an emo-tional disturbance.

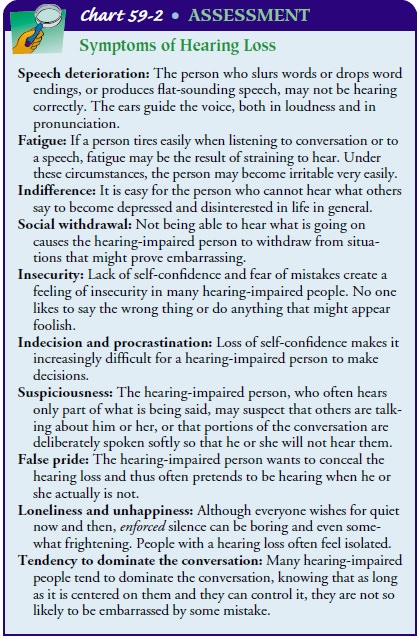

Clinical Manifestations

Early manifestations of hearing impairment and loss

may include tinnitus, increasing inability to hear in groups, and a need to

turn up the volume of the television. Hearing impairment can also trig-ger

changes in attitude, the ability to communicate, the awareness of surroundings,

and even the ability to protect oneself, affecting the person’s quality of

life. In a classroom, a student with impaired hearing may be disinterested and

inattentive and have failing grades. A person at home may feel isolated because

of an inability to hear the clock chime, the refrigerator hum, the birds sing,

or the traffic pass. A hearing-impaired pedestrian may attempt to cross the

street and fail to hear an approaching car. Hearing-impaired people may miss

parts of a conversation. Many people are unaware of their gradual hearing

impairment. Often, it is not the person with the hearing loss, but the people

with whom he or she is com-municating who recognize the impairment first (see

Chart 59-2).

For various reasons, some people with hearing loss

refuse to seek medical attention or wear a hearing aid. Others feel

self-conscious wearing a hearing aid. Insightful patients generally ask those

with whom they are trying to communicate to let them know whether difficulties

in communication exist. These attitudes and behaviors should be taken into

account when counseling patients who need hearing assistance. The decision to

wear a hearing aid is a personal one that is affected by these attitudes and

behaviors.

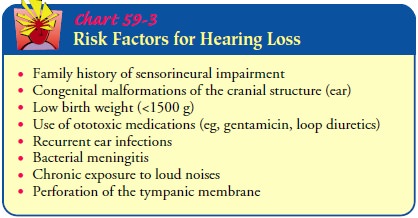

Prevention

Many environmental factors have an adverse effect on the audi-tory system and, with time, result in permanent sensorineural hearing loss. The most common is noise Noise

(ie, unwanted and unavoidable sound) has been identi-fied as one of the

environmental hazards of the 20th century. The sheer volume of noise that

surrounds us daily has increased from a simple annoyance into a potentially

dangerous source of phys-ical and psychological damage.

In terms of physical impact, loud, persistent noise

has been found to cause constriction of peripheral blood vessels, increased

blood pressure and heart rate (because of increased secretion of adrenalin),

and increased gastrointestinal activity. Additional re-search is needed to

address the overall effects of noise on the human body. It seems certain,

however, that a quiet environment is more conducive to peace of mind. A person

who is ill feels more at ease when noise is kept to a minimum. There are

numerous factors that contribute to hearing loss (see Chart 59-3).

The

term noise-induced hearing loss is

used to describe hearing loss that follows a long period of exposure to loud

noise (eg, heavy machinery, engines, artillery). Acoustic trauma refers to the hear-ing loss caused by a single

exposure to an extremely intense noise, such as an explosion. Usually,

noise-induced hearing loss occurs at a high frequency (around 4,000 Hz).

However, with contin-ued noise exposure, the hearing loss can become more

severe and include adjacent frequencies. The minimum noise level known to cause

noise-induced hearing loss, regardless of duration, is about 85 to 90 dB.

Noise exposure is inherent in many jobs (eg, mechanics, print-ers, pilots, musicians) and in hobbies such as woodworking and hunting.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration re-quires that workers wear

ear protection to prevent noise-induced hearing loss when exposed to noise

above the legal limits. There are no medications that protect against

noise-induced hearing loss; hearing loss is permanent because the hair cells in

the organ of Corti are destroyed. Ear protection against noise is the most

effective preventive measure available.

Gerontologic Considerations

About

30% of people 65 years of age and older and 50% of peo-ple 75 years and older

have hearing difficulties. The cause is un-known; linkages to diet, metabolism,

arteriosclerosis, stress, and heredity have been inconsistent (Cruickshanks et

al., 1998).

With aging, changes occur in the ear that may

eventually lead to hearing deficits. Although few changes occur in the external

ear, cerumen tends to become harder and drier, posing a greater chance of

impaction. In the middle ear, the tympanic membrane may atrophy or become

sclerotic. In the inner ear, cells at the base of the cochlea degenerate. A

familial predisposition to sensori-neural hearing loss is also seen, manifested

by a loss in the ability to hear high-frequency sounds, followed in time by the

loss of middle and lower frequencies. The term presbycusis is used to describe

this progressive hearing loss.

In

addition to age-related changes, other factors can affect hearing in the

elderly population, such as lifelong exposure to loud noises (eg, jets, guns,

heavy machinery, circular saws). Cer-tain medications, such as aminoglycosides

and aspirin, have oto-toxic effects when renal changes (eg, in the older person)

result in delayed medication excretion and increased levels of the medica-tions

in the blood. Many older people take quinine for treatment of leg cramps;

quinine can cause a hearing loss. Psychogenic fac-tors and other disease

processes (eg, diabetes) also may be partially responsible for sensorineural

hearing loss.

When

a hearing problem occurs, an evaluation is warranted. Even with the best

medical care, the person must learn to adjust to various degrees of hearing

loss. Care of elderly patients includes recognizing emotional reactions related

to hearing loss, such as suspicion of others because of an inability to hear

adequately; frustration and anger, with repeated statements such as, “I didn’t

hear what you said”; and feelings of insecurity because of the in-ability to

hear the telephone or alarms.

Medical Management

If a hearing loss is permanent or untreatable with medical or sur-gical intervention or if the patient elects not to have surgery, aural rehabilitation may be beneficial.

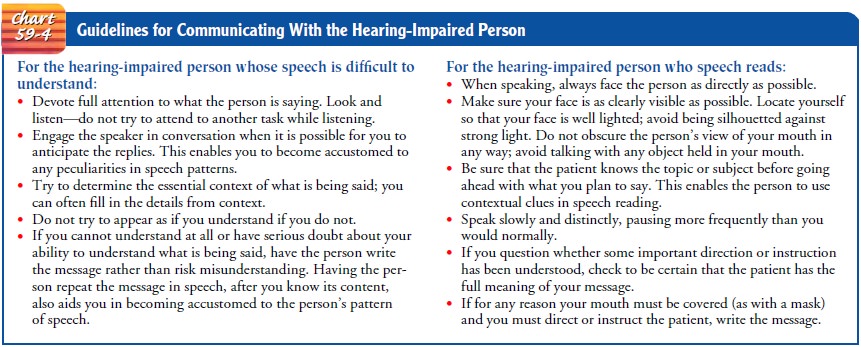

Nursing Management

The nurse who understands the different types of hearing loss will be more successful in adopting a communication style to fit the patient’s needs. Trying to speak in a loud voice to a person who cannot hear high-frequency sounds only makes understanding more difficult. However, strategies such as talking into the less impaired ear and using gestures and facial expressions can help (see Chart 59-4).major issue for many deaf and hearing-impaired people is that they have other health problems that often do not receive at-tention, in large part because of communication problems with their health care practitioners.

To effectively meet the health care needs of these patients, practitioners are legally obligated to make accommodations

for the patient’s inability to hear. Providing the services of interpreters or

those who can communicate through sign language is essential in many situations

so that the practi-tioner can effectively communicate with the patient.

During

health care and screening procedures, the practitioner (eg, dentist, physician,

nurse) must be aware that patients who are deaf or hearing impaired are unable

to read lips, see a signer, or read written materials in dark rooms required

during some diag-nostic tests. The same situation exists if the practitioner is

wear-ing a mask or not in sight (eg, x-ray studies, magnetic resonance imaging

[MRI], colonoscopy).

Nurses

and other health care practitioners must work with deaf and hearing-impaired

patients and their families to identify workable and effective means of

communication. Nurses can serve as catalysts throughout the health care system

to ensure that accommodations are made to meet the communication needs of these

patients.

Related Topics