Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Hearing and Balance Disorders

Conditions of the Inner Ear

Conditions of the Inner Ear

Disorders of balance and the vestibular system

involving the inner ear afflict more than 30 million Americans 17 years of age

or older. Falls resulting from these disorders account for more than 100,000

hip fractures in elderly people each year (NIDCD, 1998).

The term dizziness

is used frequently by patients and health care providers to describe any

altered sensation of orientation in space. Vertigo

is defined as the misperception or illusion of mo-tion of the person or the

surroundings. Most people with vertigo describe a spinning sensation or say

they feel as though objects are moving around them. Ataxia is a failure of muscular

coordination and may be present in patients with vestibular disease. Syncope,

fainting, and loss of consciousness are not forms of vertigo, nor are they

characteristic of an ear problem; they usually indicate dis-ease in the

cardiovascular system.

Nystagmus is

an involuntary rhythmic movement of the eyes.Nystagmus occurs normally when a

person watches a rapidly moving object (eg, through the side window of a moving

car or train). However, pathologically it is an ocular disorder associated with

vestibular dysfunction. Nystagmus can be horizontal, verti-cal, or rotary and

can be caused by a disorder in the central or peripheral nervous system.

MOTION SICKNESS

Motion sickness is a disturbance of equilibrium

caused by constant motion. For example, it can occur aboard a ship, while

riding on a merry-go-round or swing, or in the back seat of a car.

Clinical Manifestations

The syndrome manifests itself in sweating, pallor,

nausea, and vomiting caused by vestibular overstimulation. These

manifesta-tions may persist for several hours after the stimulation stops.

Management

Over-the-counter

antihistamines used to treat vertigo, such as di-menhydrinate (Dramamine) or

meclizine hydrochloride (Bonine), provide some relief. Anticholinergic

medications, such as scopo-lamine patches, may be helpful. These must be

replaced every few days. Side effects such as dry mouth and drowsiness occur

with these medications, which may prove to be more troublesome than helpful.

Potentially hazardous activities such as driving a car or operating heavy

machinery should be avoided if the patient experiences drowsiness.

MÉNIÈRE’S DISEASE

Ménière’s disease is an abnormal inner ear fluid

balance caused by a malabsorption in the endolymphatic sac. Evidence indicates

that many people with Ménière’s disease may have a blockage in the

endolymphatic duct. Regardless of the cause, endolymphatichydrops, a dilation in the endolymphatic space,

develops. Eitherincreased pressure in the system or rupture of the inner ear

mem-branes occurs, producing symptoms of Ménière’s disease.

Ménière’s disease affects more than 2.4 million

people in the United States. More common in adults, it has an average age of

onset in the 40s, with symptoms usually beginning between the ages of 20 and 60

years. However, the disease has been reported in children as young as age 4

years and in adults up to the 90s. Ménière’s disease appears to be equally

common in both genders. The right and left ears are affected with equal

frequency; the dis-ease occurs bilaterally in about 20% of patients. About 20%

of the patients have a positive family history for the disease (Knox &

McPherson, 1997).

Clinical Manifestations

Ménière’s

disease involves the following symptoms: fluctuating, progressive sensorineural

hearing loss; tinnitus or a roaring

sound; a feeling of pressure or fullness in the ear; and episodic,

incapac-itating vertigo, often accompanied by nausea and vomiting. The effects

of these symptoms range from a minor nuisance to ex-treme disability,

especially if the attacks of vertigo are severe. At the onset of the disease,

perhaps only one or two of the symptoms are manifested.

Some

clinicians believe that there are two subsets of the dis-ease, known as

atypical Ménière’s disease: cochlear and vestibu-lar. Cochlear Ménière’s disease

is recognized as a fluctuating, progressive sensorineural hearing loss

associated with tinnitus and aural pressure in the absence of vestibular

symptoms or findings. Vestibular Ménière’s disease is characterized as the

occurrence of episodic vertigo associated with aural pressure but no cochlear

symptoms. In some patients, cochlear or vestibular Ménière’s dis-ease develops

first. In most patients, however, all of the symptoms develop eventually.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Vertigo is usually the most troublesome complaint.

A careful his-tory is taken to determine the frequency, duration, severity, and

character of the vertigo attacks. Typically, the patient reports that vertigo

lasts minutes to hours, possibly accompanied by nausea or vomiting. Patients

also complain of diaphoresis and a persis-tent feeling of imbalance or

disequilibrium, which may last for days. They may complain of attacks that

awaken them at night. Between attacks, however, they usually feel well. The

hearing loss may fluctuate, with tinnitus and aural pressure waxing and waning

with changes in hearing. The tinnitus and feeling of aural pressure may occur

only during or before attacks, or they may be constant.

Findings

of the physical examination are usually normal, with the exception of the

evaluation of cranial nerve VIII. Sounds from a tuning fork (ie, Weber test)

may lateralize to the ear opposite the hearing loss, the one affected with

Ménière’s disease. An audiogram typically reveals a sensorineural hearing loss

in the af-fected ear. This can be in the form of a “Pike’s Peak” pattern, which

looks like a hill or mountain, or it may show a sensori-neural loss in the low

frequencies. As the disease progresses, the hearing loss increases. The

electronystagmogram may be normal or may show reduced vestibular response.

There is, however, no absolute diagnostic test.

Medical Management

Most

patients with Ménière’s disease can be successfully treated with diet and

medication therapy. Many patients can control their symptoms by adhering to a

low-sodium (2,000 mg/day) diet. The amount of sodium is one of many factors

that regulate the balance of fluid within the body. Sodium and fluid retention

disrupts the delicate balance between endolymph and perilymph in the inner ear.

Psychological evaluation may be indicated if the patient is anxious, uncertain,

fearful, or depressed.

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Pharmacologic

therapy for Ménière’s disease consists of anti-histamines such as meclizine

(Antivert), which suppress the ves-tibular system. Tranquilizers such as

diazepam (Valium) may be used in acute instances to help control vertigo.

Antiemetics such as promethazine (Phenergan) suppositories help control the

nau-sea and vomiting and the vertigo because of their antihistamine effect.

Diuretic therapy (eg, hydrochlorothiazide) sometimes re-lieves symptoms by

lowering the pressure in the endolymphatic system. Intake of foods containing

potassium (eg, bananas, toma-toes, oranges) is necessary if the patient takes a

diuretic that causes potassium loss.

Vasodilators, such as nicotinic acid, papaverine

hydrochloride (Pavabid), and methantheline bromide (Banthine), have no

sci-entific basis for alleviating the symptoms, but they are often used in

conjunction with other therapies.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Although

most patients respond well to conservative therapy, some continue to have

disabling attacks of vertigo. If these attacks reduce their quality of life,

patients may elect to undergo surgery for relief. However, hearing loss,

tinnitus, and aural fullness may continue, because the surgical treatment of

Ménière’s disease is aimed at eliminating the attacks of vertigo.

Endolymphatic Sac

Decompression.Endolymphatic sac

decom-pression, or shunting, theoretically equalizes the pressure in the

endolymphatic space. A shunt or drain is inserted in the en-dolymphatic sac

through a postauricular incision. This procedure is favored by many

otolaryngologists as a first-line surgical ap-proach to treat the vertigo of

Ménière’s disease because it is rela-tively simple and safe and can be

performed on an outpatient basis.

Middle and Inner Ear

Perfusion.Ototoxic medications,

such asstreptomycin or gentamicin, can be given to patients by infusion into

the middle and inner ear. These medications are used to de-crease vestibular

function and decrease vertigo. The success rate for eliminating vertigo is

high, about 85%, but the risk of signif-icant hearing loss is also high. This

procedure of inner ear perfu-sion usually requires an overnight stay in the

hospital. After the procedure, many patients have a period of imbalance that

lasts several weeks.

Intraotologic Catheters.In an attempt to deliver medication di-rectly to

the inner ear, catheters are being developed to provide a conduit from the

outer ear to the inner ear. The route of the catheter is from the external ear

canal through or around the tym-panic membrane and to the round window niche or

membrane. Medicinal fluids can be placed against the round window for a direct

route to the inner ear fluids.

Potential

uses of these catheters include treatment for sudden hearing loss and various

disorders causing intractable vertigo. Fu-ture applications may include

tinnitus and slowly progressing sensorineural hearing loss. Intratympanic

injections of ototoxic medications for round window membrane diffusion can be

used to decrease vestibular function. Established surgical techniques can be

used for the patient with vertigo who has not responded to medical or physical

therapeutic modalities.

Vestibular Nerve Section.Vestibular nerve section provides thegreatest success rate (approximately

98%) in eliminating the at-tacks of vertigo. It can be performed by a

translabyrinthine ap-proach (ie, through the hearing mechanism) or in a manner

that can conserve hearing (ie, suboccipital or middle cranial fossa), depending

on the degree of hearing loss. Most patients with in-capacitating Ménière’s

disease have little or no effective hearing. Cutting the nerve prevents the

brain from receiving input from the semicircular canals. This procedure

requires a brief hospital stay. Nursing care for the patient with vertigo is

presented in Plan of Nursing Care 59-1.

LABYRINTHITIS

Labyrinthitis,

an inflammation of the inner ear, can be bacterialor viral in origin. Although

rare because of antibiotic therapy, bacterial labyrinthitis usually occurs as a

complication of otitis media. The infection can enter the inner ear by

penetrating the membranes of the oval or round windows. Viral labyrinthitis is

a common medical diagnosis, but little is known about this dis-order, which

affects hearing and balance. The most commonly identified viral causes are

mumps, rubella, rubeola, and influenza. Viral illnesses of the upper

respiratory tract and herpetiform dis-orders of the facial and acoustic nerves

(ie, Ramsay Hunt syn-drome) also cause labyrinthitis.

Clinical Manifestations

Labyrinthitis

is characterized by a sudden onset of incapacitating vertigo, usually with

nausea and vomiting, various degrees of hearing loss, and possibly tinnitus.

The first episode is usually the worst; subsequent attacks, which usually occur

over a period of several weeks to months, are less severe.

Management

Treatment of bacterial labyrinthitis includes

intravenous antibiotic therapy, fluid replacement, and administration of a

vestibular sup-pressant, such as meclizine, and antiemetic medications.

Treat-ment of viral labyrinthitis is tailored to the patient’s symptoms.

BENIGN PAROXYSMAL POSITIONAL VERTIGO

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a

brief period of incapacitating vertigo that occurs when the position of the

pa-tient’s head is changed with respect to gravity, typically by plac-ing the

head back with the affected ear turned down. The onset is sudden and followed

by a predisposition for positional vertigo, usually for hours to weeks but

occasionally for months or years.

It is speculated to be caused by the disruption of

debris within the semicircular canal. This debris is formed from small crystals

of calcium carbonate from the inner ear structure, the utricle. This is

frequently stimulated by head trauma, infection, or other events. In severe

cases, vertigo may easily be induced by any head movement. The vertigo is

usually accompanied by nausea and vomiting; how-ever, hearing impairment does

not generally occur (Hain, 2002).

Bed rest is recommended for patients with acute

symptoms. Canalith repositioning procedures (CRP) may be used to provide

resolution of vertigo. The Epley procedure is a repositioning tech-nique that

is safe, inexpensive, and easy to perform for these patients. However, this

procedure is not recommended for patients with acute vertigo or for patients

diagnosed with vestibular neuronitis (a paroxysmal attack of severe vertigo).

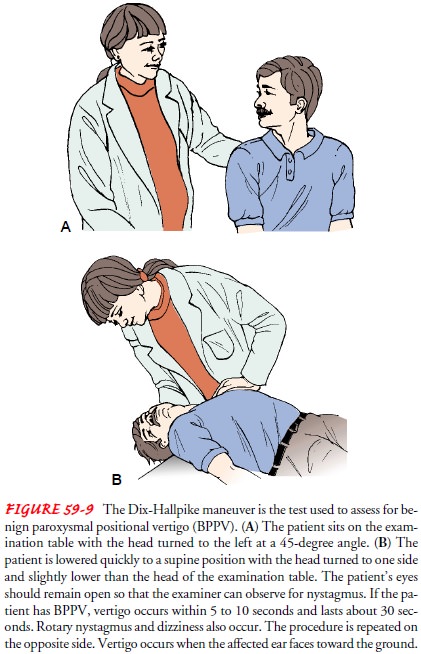

Patients with acute vertigo may be medicated with

meclizine for 1 to 2 weeks. After this time, the meclizine is stopped and the

patient is reassessed. Patients who continue to have severe posi-tional vertigo

may be premedicated with prochloperazine (Com-pazine) 1 hour before performing

the CRP. The Dix-Hallpike test is used to assess for BPPV. When the

Dix-Hallpike test results are positive on the right side, a left-sided CRP is

used (Fig. 59-9).

Vestibular

rehabilitation can be used in the management of vestibular disorders. This

strategy promotes active use of the vestibular system through a

multidisciplinary team approach, in-cluding medical and nursing care, stress

management, biofeed-back, vocational rehabilitation, and physical therapy. A

physical therapist prescribes balance exercises that help the brain com-pensate

for the impairment to the balance system.

OTOTOXICITY

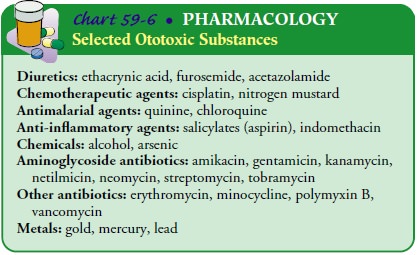

A

variety of medications may have adverse effects on the cochlea, vestibular

apparatus, or cranial nerve VIII. All but a few, such as aspirin and quinine,

cause irreversible hearing loss. At high doses, aspirin toxicity also can

produce tinnitus. Intravenous medica-tions, especially the aminoglycosides, are

the most common cause of ototoxicity, and they destroy the hair cells in the

organ of Corti (see Chart 59-6).

To

prevent loss of hearing or balance, patients receiving po-tentially ototoxic

medications should be counseled about the side effects of these medications.

Blood levels of the medications should be monitored and patients receiving

long-term intra-venous antibiotics should be monitored with an audiogram twice

each week during therapy.

ACOUSTIC NEUROMA

An acoustic neuroma is a slow-growing, benign tumor of cranial nerve VIII, usually arising from the Schwann cells of the vestibu-lar portion of the nerve. Most acoustic tumors arise within the in-ternal auditory canal and extend into the cerebellopontine angle to press on the brain stem. Acoustic neuromas account for 5% to 10% of all intracranial tumors and seem to occur with equal fre-quency in men and women at any age, although most occur during middle age. Most acoustic neuromas are unilateral, except in von Recklinghausen’s disease (ie, neurofibromatosis type 2), in which bilateral tumors occur.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

The most common findings of assessment of patients with an acoustic neuroma are unilateral tinnitus and hearing loss with or without vertigo or balance disturbance. It is important to iden-tify asymmetry in audiovestibular test results so that further workup can be performed to rule out an acoustic neuroma.

MRI with a paramagnetic contrast agent (ie, gadolinium or Magnevist)

is the imaging study of choice. If the patient is claustrophobic or cannot

tolerate an MRI or if the scan is unavailable, a computed tomography (CT) scan

with contrast dye is performed. However, MRI is more sensitive in delineating a

small tumor than is CT.

Management

Surgical removal of acoustic tumors is the

treatment of choice be-cause these tumors do not respond well to irradiation or

chemo-therapy. Because treatment of acoustic tumors crosses several

specialties, the multidisciplinary treatment approach involves a neurotologist

and a neurosurgeon. The objective of the surgery is to remove the tumor while

preserving facial nerve function. Most acoustic tumors have damaged the

cochlear portion of cranial nerve VIII, and no serviceable hearing exists before

surgery. In these patients, the surgery is performed using a translabyrinthine

approach, and the hearing mechanism is destroyed. If hearing is still good

before surgery, a suboccipital or middle cranial fossa ap-proach to removing

the tumor may be used, and intraoperative monitoring of cranial nerve VIII is

performed to save the hearing.

Complications

of surgery for acoustic neuroma include facial nerve paralysis, cerebrospinal

fluid leak, meningitis, and cerebral edema. Death from acoustic neuroma surgery

is rare.

Related Topics