Chapter: Medicine and surgery: Hepatic, biliary and pancreatic systems

Fulminant hepatic failure - Patterns of liver disease

Fulminant hepatic failure

Definition

The rapid development of severe hepatic failure causing encephalopathy and impaired synthetic function in a person who previously had a normal liver or had well-compensated liver disease.

Incidence

Rare

Aetiology

Any cause of an acute hepatitis may progress to fulminant hepatic failure. Over 50% of cases in the United Kingdom have a viral cause, most of the remainder being due to paracetamol poisoning. Other rare but important druginduced causes are halothane, isoniazid and rifampicin.

Pathophysiology

Widespread multiacinar necrosis with or without fatty change causes a severe loss of liver function. Hepatic encephalopathy is thought to be due to failure of the liver to metabolise toxins. Serum amino acid levels rise affecting the balance of cerebral neurotransmitters. Hepatic dysfunction also results in renal failure (hepatorenal syndrome).

Clinical features

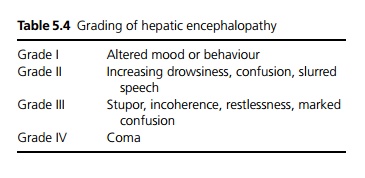

Patients may have altered behaviour, euphoria or sedation and confusion (see Table 5.4). Fever, vomiting abdominal pain and bleeding may also occur.

On examination patients are jaundiced, there may be fetor hepaticus (sickly sweet odour on breath), flapping tremor, slurred speech, difficulty in writing and copying simple diagrams (constructional apraxia) and generalised hypertonia.

Complications

· Central nervous system: Cerebral oedema in 80% causing raised intracranial pressure.

· Cardiovascular system: Hypotension, arrhythmias due to hypokalaemia including cardiac arrest.

· Respiratory system: Respiratory arrest.

· Gastrointestinal system: Haemorrhage, pancreatitis.

· Genitourinary system: Acute renal failure due to hepatorenal failure or acute tubular necrosis.

· Metabolic: Hypoglycaemia, hypokalaemia.

· Haematology: Coagulopathy.

· Infections.

Investigations

Liver function tests show hyperbilirubinaemia, high serum transaminases, abnormal coagulation profile. Liver ultrasound may be of value to show underlying chronic liver disease. Specific tests depend on the suspected underlying cause, e.g. viral serology, paracetamol levels. Other tests include full blood count, urea and electrolytes, glucose, calcium, phosphate and magnesium levels.

Management

Treatment is supportive as the liver failure may resolve:

Specialist hepatology input is essential, ideally patients should be managed in a specialist liver unit. Positioning at a 20˚ head up tilt can help ameliorate the effects of cerebral oedema. Monitoring of intracranial pressure may be necessary in severe encephalopathy. Whilst adequate nutrition is essential the protein in-take should be restricted to 0.5 g/kg/day or less. Lactulose and phosphate enemas may be used to empty the bowel and minimise the absorption of nitrogenous substances. Oral neomycin can decrease enteric bacteria. Sedatives should be avoided.

Any treatable cause, e.g. paracetamol overdose should be managed appropriately.

Complications should be anticipated and avoided wherever possible. Regular monitoring of blood glucose and 10% dextrose infusions are used to avoid hypoglycaemia. Other electrolyte imbalances should be corrected. Coagulopathy should be treated with intravenous vitamin K (although this may not be effective due to poor synthetic liver function), fresh frozen plasma should be avoided unless active bleeding is present or prior to invasive procedures as it can precipitate fluid overload. Antisecretory agents, e.g. H2 antagonists or proton pump inhibitors may reduce the risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Renal support may be necessary.

Systemic antibiotics and antifungals may be used to prevent sepsis.

Liver support using cellular and non-cellular systems are under development; however, liver transplantation remains the treatment of choice if the patient fails to improve.

Prognosis

Outcome is dependent on the degree of encephalopathy. There is over 80% mortality for those with grade IV encephalopathy. However, long-term sequelae, e.g. cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis is rare in survivors.

Related Topics