Chapter: The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology: Communities, ecosystems, and the functional role of fishes

Fishes as producers and transporters of sand, coral, and rocks

Fishes as producers and transporters of sand, coral, and rocks

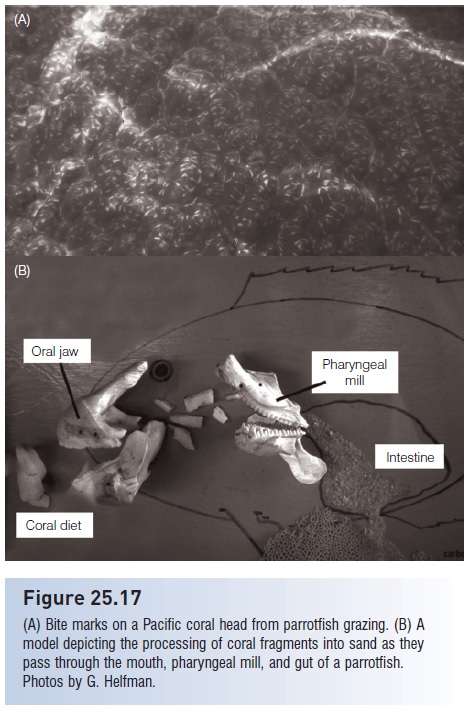

Fishes do not only move energy and nutrients around in aquatic ecosystems. They may also act as ecosystem engineers, contributing to the geological dynamics of an area. Anyone who has snorkeled on a coral reef has probably witnessed the trails of white material vented from the guts of parrotfishes. This excretory material is in part sand produced in the pharyngeal mill of the parrotfish (Fig. 25.17). Live and dead coral and coralline algae are ground up to separate the skeletal rock from algae growing on or in it (Bruggemann et al. 1996; Rotjan & Lewis 2006). Parrotfish also ingest sand trapped in algal turfs, so some sand in their stomachs is newly produced and some sand is recycled sediment. As parrotfish move about the reef, they therefore create new sand, and decrease the particle size of and redistribute old sand (Bellwood 1996).

Figure 25.17

(A) Bite marks on a Pacific coral head from parrotfish grazing. (B) A model depicting the processing of coral fragments into sand as they pass through the mouth, pharyngeal mill, and gut of a parrotfish. Photos by G. Helfman.

Estimates of bioerosion vary considerably depending on parrotfish species and depth, but have been measured in excess of 1000 kg sediment/year/m2 (Bellwood 1995b), with the highest bioerosion rates occurring in shallower reef areas and decreasing with depth (Bruggemann et al. 1996). Rates of sediment turnover can be two to five times higher than bioerosion rates (Ogden 1977; Frydl & Stearn 1978; Choat 1991). The activities of benthic-feeding fishes such as parrotfishes are the major vector of resuspension and movement of sediment on reefs in the absence of storms (Bellwood 1995a; Yahel et al. 2002). Predation on corals by parrotfishes may become an additional stressor with climate change. During the coral bleaching events that accompany temperature increases, corals that have been fed upon contain lower densities of symbiotic algae and may therefore be slower to recover (e.g., Rotjan et al. 2006).

Sand is also produced in the jaws and stomachs of other fishes that feed on corals and coralline algae, as well as those that crush mollusks and echinoderms (e.g., stingrays, emperors, wrasses, surgeonfishes, triggerfishes, puffers) (Randall 1974). Coral is moved around the reef in larger

The mounds can measure 2 m across and several centimeters high and contain hundreds of coral and shell fragments. Frequently, tilefish mounds will be the only accumulations of hard substrate in large expanses of sand. Once abandoned by the tilefish, the mounds may be colonized by large groups of newly recruited damselfishes as well as small drums, butterfl yfishes, angelfishes, and surgeonfishes (Clifton & Hunter 1972; Baird 1988).

A similar role is played by nest-building minnows in many North American streams (e.g., Nocomis, Semotilus, Exoglossum). A chub nest can contain thousands of stones as large as 1 cm across brought from several meters distance (Wallin 1989; Spawning site selection and preparation). The nest again constitutes hard substrate on an otherwise unstable bottom and is used for spawning by other species and is later colonized by various aquatic insects. The role of fishes as ecosystem engineers that affect the distribution of sediment particles via feeding and spawning activities has become more appreciated the more we investigate the phenomenon.

Related Topics