Chapter: Introduction to Human Nutrition: Digestion and Metabolism of Carbohydrates

Fermentation in the colon

Fermentation in the colon

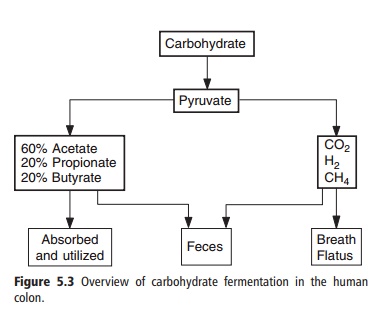

The colon contains a complex ecosystem consisting of over 400 known species of bacteria that exist in a sym-biotic relationship with the host. The bacteria obtain the substrates that they require for growth from the host, and return to the host the by-products of their metabolism. The major substrate that the bacteria receive from the host is carbohydrate, mostly in the form of polysaccharides. They obtain nitrogen from urea (which diffuses into the colon from the blood) andundigestedaminoacidsandproteins.Fermentation is the process by which microorganisms break down monosaccharides and amino acids to derive energy for their own metabolism. Fermentation reactions do not involve respiratory chains that use molecular oxygen or nitrate as terminal electron acceptors. Most of the fermentation in the human colon is anaerobic, i.e., it proceeds in the absence of a source of oxygen. Different bacteria use different substrates via different types of chemical reaction. However, as a summary of the overall process, fermentation converts carbohydrates to energy, plus various end-products, which include the gases carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and methane, and the SCFAs acetic (C2), propionic (C3), and butyric (C4) acids. Acetate, propionate, and butyrate appear in colonic contents in approximate molar ratios of 60:20:20, respectively. Most of the SCFAs produced are absorbed and provide energy for the body (Figure 5.3).

The roles of SCFAs in metabolism are discussed later. Formic acid (C1) and minor amounts of longer chain SCFAs and branched-chain SCFAs may also be produced. In addition, lactic and succinic acids and ethanol or methanol may be intermediate or end-products depending on the conditions of the fermentation. For example, rapid fermentation in an environment with a low pH results in the accumulation of lactic and succinic acids.

The first step in fermentation is the breakdown of polysaccharides, oligosaccharides, and disaccharides to their monosaccharide subunits. This is achieved either by the secretion of hydrolytic enzymes by bac-teria into the colonic lumen or, more commonly, by expression of such enzymes on the bacterial surface so that the products of hydrolysis are taken up directly by the organism producing the enzyme. To degrade the NSP of dietary fiber, the bacteria may need to attach themselves to the surface of the remnants of the plant cell walls or other particulate material.

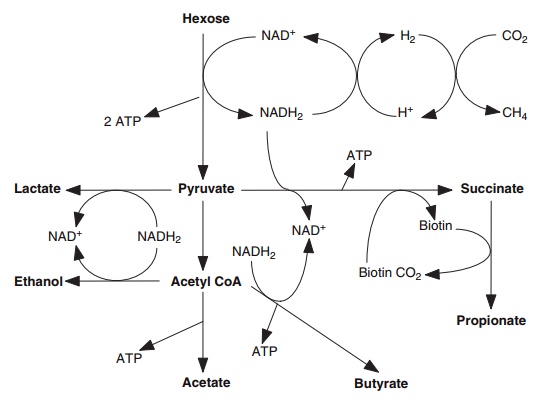

Once the monosaccharide is internalized, the majority of carbohydrate-fermenting species in the colon use the glycolytic pathway to metabolize carbo-hydrate to pyruvate. This pathway results in the reduction of NAD+ to NADH. Fermentation reactions are controlled by the need to maintain redox balance between reduced and oxidized forms of pyridine nucleotides. The regeneration of NAD+ may be achieved in a number of different ways (Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 Summary of biochemical pathways used by the anaerobic bacteria in the colon. Acetyl CoA, acetyl coenzyme A.

Electron sink products such as ethanol, lactate, hydrogen, and succinate are produced by some bacteria to regenerate oxidized pyridine nucleotides. These fermentation intermediates are subsequently fermented to SCFAs by other gut bacteria, and are important factors in maintaining species diversity in the ecosystem.

Related Topics