Chapter: Introduction to Human Nutrition: Digestion and Metabolism of Carbohydrates

Fate of short-chain fatty acids

Fate of short-chain fatty acids

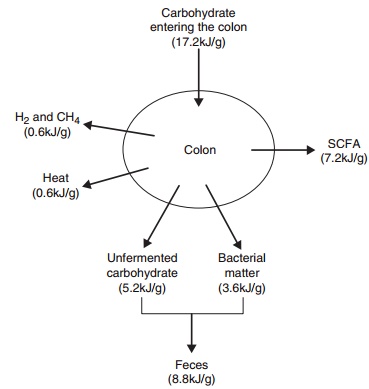

Colonic fermentation can be viewed as a way in which the human host can recover part of the energy of malabsorbed carbohydrates. The amount of energy recovered from fermentation depends on the fer-mentability of the carbohydrate (which can range from 0% to 100%) and the nature of the products of fermentation. On a typical Western diet, about 40– 50% of the energy in carbohydrate that enters the colon is available to the human host as SCFAs. The rest of the energy is unavailable to the host, being lost as heat or unfermented carbohydrate or used to produce gases or for bacterial growth (Figure 5.5).

SCFAs are almost completely absorbed and, while some butyrate is oxidized by colonocytes (the epithe-lial cells lining the colon), most arrives at the liver via the portal vein. Propionate and butyrate are removed in first pass through the liver, but increased concen-trations of acetate can be observed in peripheral blood several hours after consumption of indigestible but fermentable carbohydrates. These absorbed

Figure 5.5 Quantitative fate of carbohydrate in the colon. SCFA, short-chain fatty acid.

There is considerable interest in the possible effects of individual SCFAs on the health of the colon and the whole body. The strongest evidence to date is for an anticancer effect of butyrate, which may be due to the ability of butyrate to induce differentiation and apoptosis (programmed cell death) of colon cancer cells. There is some support for the hypothesis that propionate may help to reduce the risk of cardiovas-cular disease by lowering blood cholesterol concen-tration and/or by an effect on hemostasis, but the evidence so far is not conclusive.

Related Topics