Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Musculoskeletal Trauma

Femoral Shaft - Fracture

FEMORAL SHAFT

Considerable force is required to break the shaft of the

femur in adults. Most femoral fractures are seen in young adults who have been

involved in a motor vehicle crash or who have fallen from a high place.

Frequently, these patients have associated multiple traumas.

The patient presents

with an enlarged, deformed, painful thigh and cannot move the hip or the knee.

The fracture may be trans-verse, oblique, spiral, or comminuted. Frequently,

the patient develops shock, because the loss of 2 to 3 units of blood into the

tis-sues is common with these fractures. An expanding diameter of the thigh may

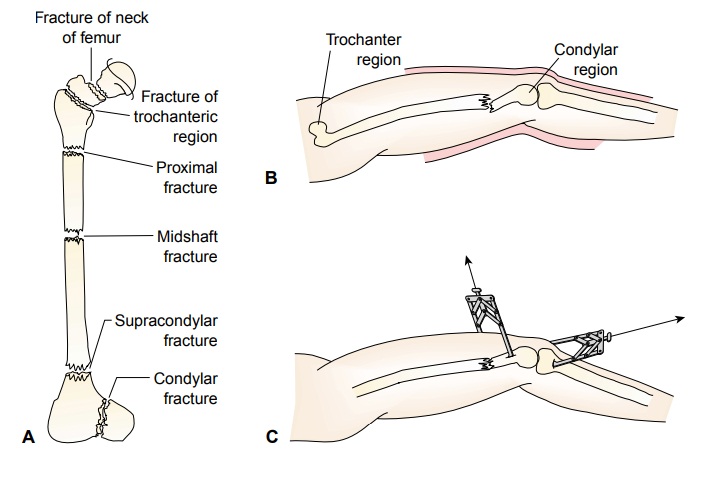

indicate continued bleeding. Refer to Figure 69-15A for the types of femoral

fractures.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Assessment includes checking the neurovascular status of

the ex-tremity, especially circulatory perfusion of the lower leg and foot

(popliteal, posterior tibial, and pedal pulses and toe capillary re-fill time).

A Doppler ultrasound monitoring device may be needed to assess blood flow.

Dislocation of the hip and knee may accompany these fractures. Knee effusion

suggests ligament damage and possible instability of the knee joint.

Medical Management

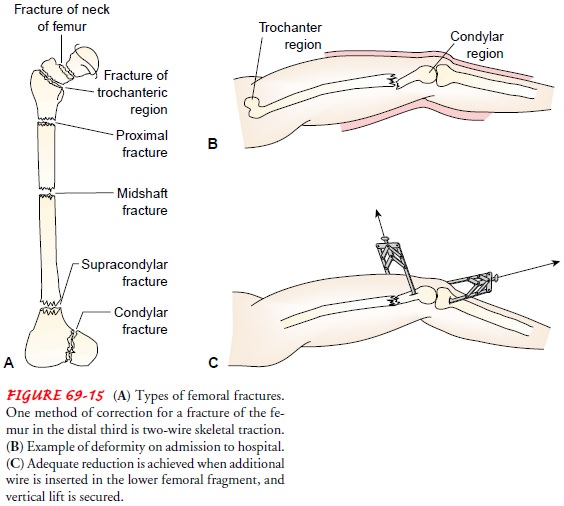

Continued neurovascular

monitoring is needed. The fracture is immobilized so that additional soft

tissue damage does not occur. Generally, skeletal traction (Fig. 69-15 B and C)

or splinting is used to immobilize fracture fragments until the patient is

physio-logically stable and ready for open reduction and internal fixation

procedures.

Internal fixation usually is carried out within a few

days after injury. Intramedullary locking nail devices are used for midshaft

(diaphyseal) fractures. Depending on the supracondylar frac-ture pattern,

intramedullary nailing or screw plate fixation may be used. Internal fixation

permits early mobilization. A thigh cuff orthosis may be used for external

support. To preserve muscle strength, the patient is instructed to exercise the

lower leg, foot, toes, and hip on a regular basis. Active muscle movement

enhances healing by increasing blood supply and electrical potentials at the

fracture site. Prescribed weight-bearing limits are based on the fracture

pattern. Physical therapy includes ROM and strengthen-ing exercises, safe use

of ambulatory aids, and gait training. Func-tional ambulation stimulates

fracture healing. Healing time is 4 to 6 months.

Compression plates and intramedullary nails may need to

be removed after 12 to 18 months due to reaction or loosen-ing. After plates

are being removed, a thigh cuff orthosis is used for several months to provide

support while bone remodeling occurs.

Infrequently, because of patient risks associated with

anesthe-sia and surgery, middle shaft and distal (supracondylar) fractures may

be managed with skeletal traction. Between 2 and 4 weeks after injury, when

pain and swelling have subsided, the patient is removed from skeletal traction

and placed in a cast brace. The cast brace is a total contact device (ie,

encircles the limb) and holds the reduced fracture. The muscle, through

hydrodynamic compression, stabilizes the bone and stimulates healing. Mini-mal

partial weight bearing is begun and is progressed to full weight bearing as

tolerated. The cast brace is worn for 12 to 14 weeks.

An external fixator may be used if the patient has

experienced an open fracture, has extensive soft tissue trauma, has lost bone,

has an infection, or has hip and tibial fractures.

A common complication after fracture of the femoral shaft

is restriction of knee motion. Active and passive knee exercises begin as soon

as possible, depending on the management approach and the stability of the

fracture and knee ligaments. Other compli-cations include malunion, delayed

union or nonunion, pudendal nerve palsy, and infection.

Related Topics