Chapter: Basic & Clinical Pharmacology : Diuretic Agents

Edematous States

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OF DIURETIC AGENTS

A

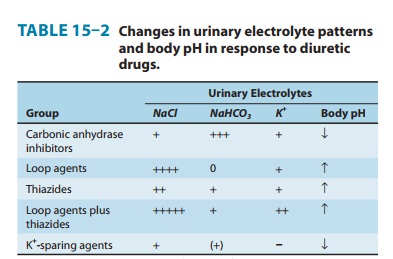

summary of the effects of diuretics on urinary electrolyte excre-tion is shown

in Table 15–2.

EDEMATOUS STATES

A

common reason for diuretic use is for reduction of peripheral or pulmonary

edema that has accumulated as a result of cardiac, renal, or vascular diseases

that reduce blood flow to the kidney. This reduction is sensed as insufficient

effective arterial blood volume and leads to salt and water retention, which

expands blood volume and eventually causes edema formation. Judicious use of

diuretics can mobilize this interstitial edema without significant reductions

in plasma volume. However, excessive diuretic therapy may compromise the

effective arterial blood volume and reduce the perfusion of vital organs.

Therefore, the use of diuretics to mobilize edema requires careful monitoring

of the patient’s hemo-dynamic status and an understanding of the

pathophysiology of the underlying illness.

HEART FAILURE

When

cardiac output is reduced by heart failure, the resultant changes in blood

pressure and blood flow to the kidney are sensed as hypovolemia and lead to

renal retention of salt and water. This physiologic response initially

increases intravascular volume and venous return to the heart and may partially

restore the cardiac output toward normal .

If

the underlying disease causes cardiac output to deteriorate despite expansion

of plasma volume, the kidney continues to retain salt and water, which then

leaks from the vasculature and becomes interstitial or pulmonary edema. At this

point, diuretic use becomes necessary to reduce the accumulation of edema,

par-ticularly in the lungs. Reduction of pulmonary vascular conges-tion with

diuretics may actually improve oxygenation and thereby improve myocardial

function. Reduction of preload can reduce the size of the heart, allowing it to

work at a more efficient fiber length. Edema associated with heart failure is

generally managed with loop diuretics. In some instances, salt and water

retention may become so severe that a combination of thiazides and loop

diuretics is necessary.

In

treating the heart failure patient with diuretics, it must always be remembered

that cardiac output in these patients is being maintained in part by high

filling pressures. Therefore, excessive use of diuretics may diminish venous

return and further impair cardiac output. This is especially critical in right

ventricular heart failure. Systemic, rather than pulmonary vascular,

conges-tion is the hallmark of this disorder. Diuretic-induced volume

contraction predictably reduces venous return and can severely compromise

cardiac output if left ventricular filling pressure is reduced below 15 mm Hg .

Reduction in cardiac output, resulting from either left or right ventricular

dysfunction, also eventually leads to renal dysfunction resulting from reduced

perfusion pressures.

Increased

delivery of salt to the TAL leads to activation of the macula densa and a

reduction in GFR by tubuloglomerular feed-back. The mechanism of this feedback

is secretion of adenosine by macula densa cells, which causes afferent arteriolar

vasoconstric-tion through activation of A1 adenosine receptors on

the afferent arteriole. This vasoconstriction reduces GFR. Tubuloglomerular

feedback–mediated reduction in GFR exacerbates the reduction that was initially

caused by decreased cardiac output. Recent work with adenosine receptor

antagonists has shown that it may soon be possible to circumvent this

complication of diuretic therapy in heart failure patients by blunting

tubuloglomerular feedback.

Diuretic-induced

metabolic alkalosis, exacerbated by hypo-kalemia, is another adverse effect

that may further compromise cardiac function. This complication can be treated

with replacement of K+ and restoration of intravascular volume with saline; however,

severe heart failure may preclude the use of saline even in patients who have

received excessive diuretic therapy. In these cases, adjunc-tive use of

acetazolamide helps to correct the alkalosis.

Another

serious toxicity of diuretic use in the cardiac patient is hypokalemia.

Hypokalemia can exacerbate underlying cardiac arrhythmias and contribute to

digitalis toxicity. This can usually be avoided by having the patient reduce Na+ intake while taking

diuretics, thus decreasing Na+ delivery to the K+-secreting collect-ing tubule. Patients who are noncompliant

with a low Na+ diet must take oral KCl supplements or a K+-sparing diuretic.

KIDNEY DISEASE AND RENAL FAILURE

A

variety of diseases interfere with the kidney’s critical role in volume

homeostasis. Although some renal disorders cause salt wasting, most cause

retention of salt and water. When renal failure is severe (GFR < 5 mL/min),

diuretic agents are of little benefit, because glomerular filtration is

insufficient to generate or sustain a natriuretic response. However, a large

number of patients, and even dialysis patients, with milder degrees of renal

insufficiency (GFR of 5–15 mL/min), can be treated with diuretics when they retain

excessive volumes of fluid between dialysis treatments.

There

is still interest in the question as to whether diuretic therapy can alter the

severity or the outcome of acute renal failure. This is because “nonoliguric”

forms of acute renal insufficiency have better outcomes than “oliguric” (<

400–500 mL/24 h urine output) acute renal failure. Almost all studies of this

question have shown that diuretic therapy helps in the short-term fluid

manage-ment of these patients with acute renal failure, but that it has no

impact on the long-term outcome.

Many

glomerular diseases, such as those associated with diabe-tes mellitus or

systemic lupus erythematosus, exhibit renal reten-tion of salt and water. The

cause of this sodium retention is not precisely known, but it probably involves

disordered regulation of the renal microcirculation and tubular function

through release of vasoconstrictors, prostaglandins, cytokines, and other

mediators. When edema or hypertension develops in these patients, diuretic

therapy can be very effective.

Certain

forms of renal disease, particularly diabetic nephropa-thy, are frequently

associated with development of hyperkalemia at a relatively early stage of

renal failure. In these cases, a thiazide or loop diuretic will enhance K+ excretion by

increasing delivery of salt to the K+-secreting collecting

tubule.

Patients

with renal diseases leading to the nephrotic syndrome often present complex

problems in volume management. These patients may exhibit fluid retention in

the form of ascites or edema but have reduced plasma volume due to reduced

plasma oncotic pressures. This is very often the case in patients with “minimal

change” nephropathy. In these patients, diuretic use may cause further

reductions in plasma volume that can impair GFR and may lead to orthostatic

hypotension. Most other causes of nephrotic syndrome are associated with

primary retention of salt and water by the kidney, leading to expanded plasma

volume and hypertension despite the low plasma oncotic pressure. In these

cases, diuretic therapy may be beneficial in controlling the volume-dependent

component of hypertension.

In

choosing a diuretic for the patient with kidney disease, there are a number of

important limitations. Acetazolamide must usually be avoided because it causes

NaHCO3 excretion and can exacerbate acidosis. Potassium-sparing

diuretics may cause hyperkalemia. Thiazide diuretics were previously thought to

be ineffective when GFR falls below 30 mL/min. More recently, it has been found

that thiazides, which are of little ben-efit when used alone, can be used to

significantly reduce the dose of loop diuretics needed to promote diuresis in a

patient with GFR of 5–15 mL/min. Thus, high-dose loop diuretics (up to 500 mg

of furosemide/d) or a combination of metolazone (5–10 mg/d) and much smaller

doses of furosemide (40–80 mg/d) may be useful in treating volume overload in

dialysis or predialysis patients. There has been some interest in the use of

osmotic diuretics such as mannitol, because this drug can shrink swollen

epithelial cells and may theoretically reduce tubular obstruction.

Unfortunately, there is no evidence that mannitol can prevent ischemic or toxic

acute renal failure. Mannitol may be useful in the management of hemoglobinuria

or myoglobinuria. Lastly, although excessive use of diuretics can impair renal

function in all patients, the consequences are obviously more serious in

patients with underlying renal disease.

HEPATIC CIRRHOSIS

Liver

disease is often associated with edema and ascites in con-junction with

elevated portal hydrostatic pressures and reduced plasma oncotic pressures.

Mechanisms for retention of Na+ by the kidney in this setting include diminished renal

perfusion (from systemic vascular alterations), diminished plasma volume (due

to ascites formation), and diminished oncotic pressure (hypoalbu-minemia). In

addition, there may be primary Na+ retention due to elevated plasma aldosterone levels.

When

ascites and edema become severe, diuretic therapy can be very useful. However,

cirrhotic patients are often resistant to loop diuretics because of decreased

secretion of the drug into the tubular fluid and because of high aldosterone

levels. In contrast, cirrhotic edema is unusually responsive to spironolactone

and eplerenone. The combination of loop diuretics and an aldosterone receptor

antagonist may be useful in some patients. However, considerable caution is

necessary in the use of aldosterone antago-nists in cirrhotic patients with

even mild renal insufficiency because of the potential for causing serious

hyperkalemia.

It

is important to note that, even more than in heart failure, overly aggressive

use of diuretics in this setting can be disastrous. Vigorous diuretic therapy

can cause marked depletion of intra-vascular volume, hypokalemia, and metabolic

alkalosis. Hepatorenal syndrome and hepatic encephalopathy are the unfortunate

consequences of excessive diuretic use in the cir-rhotic patient.

IDIOPATHIC EDEMA

Idiopathic

edema (fluctuating salt retention and edema) is a syn-drome found most often in

20–30 year-old women. Despite intensive study, the pathophysiology remains

obscure. Some stud-ies suggest that surreptitious, intermittent diuretic use

may actu-ally contribute to the syndrome and should be ruled out before

additional therapy is pursued. While spironolactone has been used for

idiopathic edema, it should probably be managed with moder-ate salt restriction

alone if possible. Compression stockings have also been used but appear to be

of variable benefit.

Related Topics