Chapter: Software Architectures : Documenting the Architecture

Documenting a View

Documenting

a View

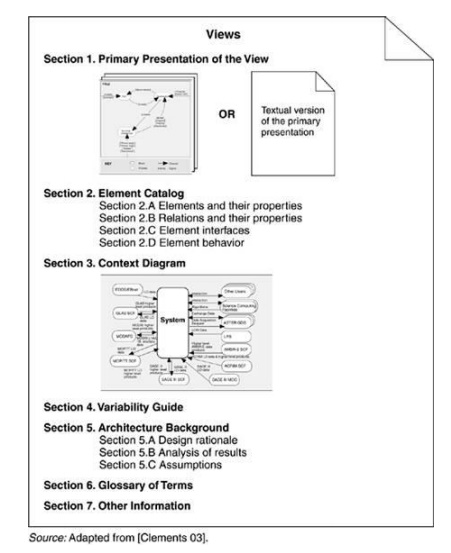

There is no industry-standard template for documenting a

view, but the seven-part standard organization that we suggest in this section

has worked well in practice. First of all, whatever sections you choose to

include, make sure to have a standard

organization. Allocating specific information to specific sections will help

the documentation writer attack the task and recognize completion, and it will

help the documentation reader quickly find information of interest at the

moment and skip everything else.

1.

Primary presentation shows the elements and the

relationships among them that populate

the view. The primary presentation should contain the information you wish to

convey about the system (in the vocabulary of that view) first. It should

certainly include the primary elements and relations of the view, but under

some circumstances it might not include all of them. For example, you may wish

to show the elements and relations that come into play during normal operation,

but relegate error handling or exceptional processing to the supporting

documentation.

The primary presentation is

usually graphical. In fact, most graphical notations make their contributions

in the form of the primary presentation and little else. If the primary presentation

is graphical, it must be accompanied by a key that explains, or that points to

an explanation of, the notation or symbology used.

Sometimes the primary

presentation can be tabular; tables are often a superb way to convey a large

amount of information compactly.

A textual presentation still

carries the obligation to present a terse summary of the most important

information in the view.

2.

Element catalog details at least those elements

and relations depicted in the primary

presentation, and perhaps others. Producing the primary presentation is often

what architects concentrate on, but without backup information that

explains the picture, it is of

little value. For instance, if a diagram shows elements A, B, and C, there had

better be documentation that explains in sufficient detail what A, B, and C

are, and their purposes or the roles they play, rendered in the vocabulary of

the view. For example, a module decomposition view has elements that are

modules, relations that are a form of "is part of," and properties

that define the responsibilities of each module. A process view has elements

that are processes, relations that define synchronization or other

process-related interaction, and properties that include timing parameters.

In addition, if there are

elements or relations relevant to the view that were omitted from the primary

presentation, the catalog is where those are introduced and explained.

The behavior and interfaces of

elements are two other aspects of an element catalog; these will be discussed

shortly.

3. Context diagram shows how the system depicted in the view relates to its environment in the vocabulary of the

view. For example, in a component-and- connector view you show which component

and connectors interact with external components and connectors, via which

interfaces and protocols.

4.

Variability guide shows how to exercise any

variation points that are a part of the architecture

shown in this view. In some architectures, decisions are left unbound until a

later stage of the development process, and yet the architecture must still be

documented. An example of variability is found in software product lines where

the product line architecture is suitable for multiple particular systems

. A variability guide should

include documentation about each point of variation in the architecture,

including

-

the options among which a choice is to be made. In a module

view, the options are the various versions or parameterizations of modules. In

a component-and-connector view, they might include constraints on replication,

scheduling, or choice of protocol. In an allocation view, they might include

the conditions under which a software element would be allocated to a

particular processor.

-

the binding time of the option. Some choices are made at design

time, some at build time, and others at runtime.

5.

Architecture background explains why the design

reflected in the view came to be. The

goal of this section is to explain to someone why the design is as it is and to

provide a convincing argument that it is sound. An architecture background

includes

-

rationale, explaining why the decisions reflected in the view

were made and why alternatives were rejected.

-

analysis results, which justify the design or explain what would

have to change in the face of a modification.

-

assumptions reflected in the design.

6.

Glossary of terms used in the views, with a brief

description of each.

7.

Other information. The precise contents of this

section will vary according to the standard

practices of your organization. They might include management information such

as authorship, configuration control data, and change histories. Or the

architect might record references to specific sections of a requirements

document to establish traceability. Strictly speaking, information such as this

is not architectural. Nevertheless, it is convenient to record it alongside the

architecture, and this section is provided for that purpose. In any case, the

first part of this section must detail its specific contents.

Figure 9.1. The seven

parts of a documented view

Related Topics