Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Breast Disorders

Diagnostic Evaluation of Patients With Breast Disorders

Diagnostic Evaluation

BREAST SELF-EXAMINATION

BSE

instruction can be performed during assessment as part of the physical

examination; it can be taught in any setting, either to individuals or groups.

Instructions about BSE are provided to men if they have a family history of

breast cancer because these men may be at higher risk for male breast cancer.

Variations

in breast tissue occur during the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and menopause.

Therefore, normal changes must be distinguished from those that may signal

disease. Most women notice increased tenderness and lumpiness before their

menstrual period; therefore, BSE is best performed after menses (day 5 to day

7, counting the first day of menses as day 1), when less fluid is retained.

Also, many women have grainy-textured breast tissue, but these areas are

usually less nodular after menses.

Because

women themselves detect many breast cancers, prior-ity is given to teaching all

women how and when to examine their breasts (Chart 48-2). It is estimated that

only 25% to 30% of women perform BSE proficiently and regularly each month.

Younger women, who have normal lumps in their breasts, find it particularly

difficult to perform BSE because they have a harder time distinguishing normal

from abnormal lumps and are not sure of what they are feeling due to the

density of their breast tissue. Even women who perform BSE may delay seeking

medical atten-tion because of fear, economic factors, lack of education,

reluctance to act if no pain is involved, psychological factors, and modesty.

Women

should begin practicing BSE at the time of their first gynecologic examination,

which usually occurs in their late teens or early 20s. All health care

providers, aware of these implica-tions, should encourage women to examine

their own breasts and teach them to recognize early changes that may indicate

prob-lems. The nurse plays a pivotal role in preventive education. Almost all

settings lend themselves to teaching, providing infor-mation, and encouraging

appropriate care for prevention, detec-tion, and treatment of breast problems.

An individual teaching session with the patient can increase the frequency with

which she practices BSE.

A

lesson in BSE should include the following: optimal timing for BSE (5 to 7 days

after menses begin for premenopausal women and once monthly for postmenopausal

women), a demonstration of examination techniques, a review of what normal

breast tissue feels like, a discussion on identification of breast changes, and

a return demonstration on the patient and a breast model. Patients who have had

breast surgery for the treatment of breast cancer are carefully instructed to

examine themselves for any nodules or changes in their breasts or along the

chest wall that may indicate a recurrence of the disease.

Films

or videos about BSE, shower cards, and pamphlets can be obtained from local c

hapters of the American Cancer Society. The National Cancer Institute in

Bethesda, Maryland, offers a program that teaches nurses to instruct patients

in BSE and also provides teaching aids. The National Alliance for Breast Cancer

Organizations, a clearinghouse for lay materials on breast cancer education, is

another resource.

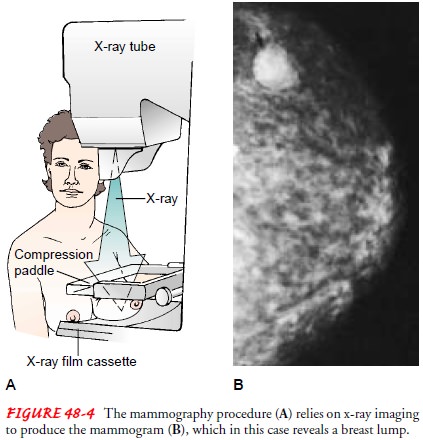

MAMMOGRAPHY

Mammography is a breast-imaging technique that can

detectnonpalpable lesions and assist in diagnosing palpable masses. The

procedure takes about 20 minutes and can be performed in an x-ray department or

independent imaging center. Two views are taken of each breast: a craniocaudal

view and a mediolateral oblique view. For these views, the breast is

mechanically com-pressed from top to bottom and side to side (Fig. 48-4). Women

may experience some fleeting discomfort because maximum compression is

necessary for proper visualization. The current mammograms are compared with

previous mammograms, and any changes indicate a need for further investigation.

Mammog-raphy may detect a breast tumor before it is clinically palpable (ie,

smaller than 1 cm); however, it has limitations and is not fool-proof. The false-negative

rate ranges between 5% and 10%; it is generally greater in younger women with

greater density of breast tissue. Some patients have very dense breast tissue,

making it dif-ficult to detect lesions with mammography.

Patients scheduled for a mammogram may voice concern about exposure to radiation. The radiation exposure is equivalent to about 1 hour of exposure to sunlight, so patients would have to have many mammograms in a year to increase their cancer risk.

The benefits of

this test outweigh the risks. Because the quality of mammography varies widely

from one setting to the next, it is important for women to find accredited

breast care centers that produce reliable mammograms.

Current

mammographic screening guidelines from the Amer-ican Cancer Society recommend a

mammogram every year start-ing at the age of 40 years. A baseline mammogram

should be obtained after the age of 35 years and by the age of 40. Younger

women who are identified as at a higher risk for breast cancer by family

history should seek the opinion of a breast specialist about when to begin

screening mammograms. Several studies suggest that screening for high-risk

women should begin about 10 years before the age of diagnosis of the family

member with breast can-cer (Hartmann, Sellers, Schaid et al., 1999). In

families with a history of breast cancer, a downward shift in age of diagnosis

of about 10 years is seen (eg, grandmother diagnosed with breast cancer at age

48, mother diagnosed with breast cancer at age 38, then daughter should begin

screening at age 28). Nurses need to provide teaching about screening

guidelines for women in the general population and those at high risk so that

these women can make informed choices about screening.

The

combination of screening mammography, physical ex-amination, and BSE has

reduced overall mortality from breast cancer by 63% among women ages 40 to 69

years (Tabar, Vitak, Tony et al., 2001). Despite the decreased mortality

associated with mammographic screening, it has not been used equitably across

the U.S. population. Current statistics indicate that 67% of women 40 years of

age and over have had a mammogram within the past 2 years (CDC Database, 2000).

Women with fewer resources (eg, elderly, poor, minority women, women with-out

health insurance) often do not have the means to undergo mammography or the

resources for follow-up treatment when le-sions are detected. Recent studies

have shown that social support contributes to adherence to mammographic

screening guidelines (Anderson, Urban & Etzioni, 1999; Faccione, 1999;

Lauver, Kane, Bodden et al., 1999). Many nurses direct their efforts at

educating women about the benefits of mammography. Work-ing to overcome

barriers to screening mammography, especially among the elderly and women with

disabilities, is an important nursing intervention in the community, and nurses

have an im-portant role in the development of educational materials targeted to

specific literacy levels and ethnic groups.

Galactography

Galactography is a mammographic diagnostic procedure that

in-volves injection of less than 1 mL of radiopaque material through a cannula

inserted into a ductal opening on the areola, followed by a mammogram. It is

performed when the patient has a bloody nipple discharge on expression,

spontaneous nipple discharge, or a solitary dilated duct noted on mammography.

These symptoms may indicate a benign lesion or a cancerous one.

ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Ultrasonography (ultrasound) is used in conjunction with

mam-mography to distinguish fluid-filled cysts from other lesions. A transducer

is used to transmit high-frequency sound waves through the skin and into the

breast, and an echo signal is measured. The echo waves are interpreted

electronically and then displayed on a screen. This technique is 95% to 99%

accurate in diagnosing cysts but does not definitively rule out a malignant

lesion.

For

women with dense breasts, the introduction of screening ultrasound examinations

has been researched during this past decade. The addition of ultrasonography to

breast cancer screen-ing can increase the sensitivity of screening for this

population of women, who tend to be either young or on hormone replacement

therapy. The largest study showed an increase in cancer detection by 17% with

the addition of screening ultrasonography (Kolb, Lichy & Newhouse, 1998).

Further research will help provide information on the usefulness of ultrasound

as a screening modality.

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

Magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) of the breast is a promising tool for use in diagnosing

breast conditions. It is a highly sensi-tive, although not specific, test and

serves as an adjunct to mam-mography. A coil is placed around the breast, and

the patient is placed inside the MRI machine for about 2 minutes. An injection

of gadolinium, a contrast dye, is given intravenously. MRI of the breast can be

helpful in determining the exact size of a lesion or the presence of multiple

foci more precisely than mammography. It also can determine more precisely than

a CT scan if a lesion is fixed to the chest wall. Other uses include

identifying occult (undetectable) breast cancer, determining the tumor’s

response to chemotherapy, and determining the integrity of saline or sili-cone

breast implants. The cost of breast MRI, however, is high; therefore, it is not

currently used for routine screening. However, the sensitivity of the MRI may

be beneficial for cancer detection in higher-risk women, and the results from

preliminary studies are encouraging (Schnall, 2001).

PROCEDURES FOR TISSUE ANALYSIS

Fine-Needle Aspiration

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is an outpatient procedure usu-ally

initiated when mammography, ultrasonography, or palpa-tion detects a lesion. A

surgeon performs the procedure when there is a palpable lesion, or a

radiologist performs it under x-ray guidance for nonpalpable lesions. Injection

of a local anesthetic may or may not be used, but most times the surgeon or

radiol-ogist inserts a 21- or 22-gauge needle attached to a syringe into the

site to be sampled. The syringe is then used to withdraw tis-sue or fluid into

the needle. This cytologic material is spread on a slide and sent to the

laboratory for analysis. FNA is less expen-sive than other diagnostic methods,

and results are usually avail-able quickly; however, this diagnostic test is

often not 100% accurate, and the false-negative rate is substantial.

False-negative or false-positive results are possible, and clinical follow-up

depends on the level of suspicion about the breast lesion.

Stereotactic Biopsy

Stereotactic biopsy, also an outpatient procedure, is

performedfor nonpalpable lesions found on mammography. The patient lies prone

on a special table, and the breast is positioned through an opening in the

table and compressed for a mammogram. The lesion to be sampled is then located

with the aid of a computer. Next, a local anesthetic is injected into the entry

site on the breast, a core needle is inserted, and samples of the tissue are

taken for pathologic examination. If the lesion is small, a clip is placed at

the site of the biopsy, so that a specific area can be visualized again as

another mammogram is performed. This technique allows accurate diagnosis and

often allows the patient to avoid a surgical biopsy, although some patients may

end up needing a surgical biopsy, depending on the pathologic diagnosis.

Surgical Biopsy

Surgical biopsy is the most common outpatient surgical

proce-dure. Eight of 10 lesions are benign on biopsy. The procedure is usually

done using local anesthesia, moderate sedation, or both. The biopsy involves

excising the lesion and sending it to the lab-oratory for pathologic

examination.

EXCISIONAL BIOPSY

Excisional

biopsy is the usual procedure for any palpable breast mass. The entire lesion,

plus a margin of surrounding tissue, is re-moved. This type of biopsy may also

be referred to as a lumpec-tomy. Depending on the clinical situation, a frozen

section may be done at the time of the biopsy (a small piece of the mass or

le-sion is given a provisional diagnosis by the pathologist), so that the

surgeon can provide the patient with a diagnosis in the re-covery room.

INCISIONAL BIOPSY

Incisional

biopsy is performed when tissue sampling alone is re-quired; this is done both

to confirm a diagnosis and to determine the hormonal receptor status. Complete

excision of the area may not be possible or immediately beneficial to the

patient, depend-ing on the clinical situation. This procedure is often

performed in women with locally advanced breast cancer or in cancer pa-tients with

a suspicion of recurrent disease, whose treatment may depend on the tumor’s

estrogen and progesterone receptor status. These receptors are identified

during pathologic examination of the tissue.

TRU-CUT CORE BIOPSY

In a

Tru-Cut core biopsy, the surgeon uses a special large-lumen needle to remove a

core of tissue. This procedure is used when a tumor is relatively large and

close to the skin surface and the sur-geon strongly suspects that the lesion is

a carcinoma. If cancer is diagnosed, the tissue is also tested for hormone

receptor status.

WIRE NEEDLE LOCALIZATION

Wire needle localization is a technique used when

mammogra-phy detects minute, pinpoint calcifications (indicating a poten-tial

malignancy) or nonpalpable lesions and a biopsy is necessary. A long, thin wire

is inserted, usually painlessly, through a needle before the excisional biopsy

under mammographic guidance to ensure that the wire tip designates the area to

undergo biopsy. The wire remains in place after the needle is withdrawn to ensure

a precise biopsy. The patient is then taken to the operating room, where the

surgeon follows the wire down and excises the area around the wire tip. The

tissue removed is x-rayed at the time of the procedure; these specimen x-rays,

along with follow-up mammograms taken several weeks later (after the site has

healed), verify that the area of concern was located and removed.

Related Topics