Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Breast Disorders

Breast Cancer: Medical Management

Medical

Management

CHANGING APPROACHES

In

1990, the National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference on

Breast Cancer issued its third statement on the management of breast cancer.

Based on worldwide data, breast-conserving surgery (such as lumpectomy), along

with radiation therapy, was found to result in a survival rate equal to that of

modified radical mastectomy. In addition, recommendations were made for

systemic treatment with chemotherapy based on the patient’s menopausal status

and the presence of hormone re-ceptors. For a premenopausal woman without involvement

of the lymph nodes, adjuvant chemotherapy was recommended if the woman was at

high risk for recurrence. For a postmenopausal woman without involvement of the

lymph nodes, adjuvant chemo-therapy was not recommended regardless of hormonal

receptor status. For a premenopausal woman with involvement of the nodes,

adjuvant chemotherapy was recommended. In a postmenopausal woman, hormone

therapy was recommended if the woman had an estrogen receptor-positive tumor.

In

1991, the National Cancer Institute issued a clinical alert that altered the

recommendations of the 1990 Consensus Devel-opment Conference Statement. This

alert recommended that all premenopausal, node-negative women at high risk for

recurrent disease receive adjuvant chemotherapy. This clinical alert was

is-sued before the results of clinical trials were published, creating

confusion among clinicians and patients alike. The 2000 Con-sensus Development

Conference Statement stated that all women with invasive breast cancer should

consider systemic chemother-apy, not just women with tumors larger than 1 cm

(NIH, 2000).

Decisions

regarding local treatment with either mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery

with radiation still vary widely. Mas-tectomy is still performed in many cases,

and rates for breast-conserving surgery are higher in metropolitan areas with

teaching and research hospitals and medical centers. In the past, women have

not routinely been presented with the option of breast-conserving surgery by

their physicians, and in many instances in-surance reimbursement patterns favor

mastectomy. Thus, women have not uniformly had the opportunity to exercise

informed choice in their options for local treatment, but this is changing as

women become more knowledgeable about breast cancer and its treatment. A second

opinion regarding treatment options is usu-ally helpful to women diagnosed with

breast cancer.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

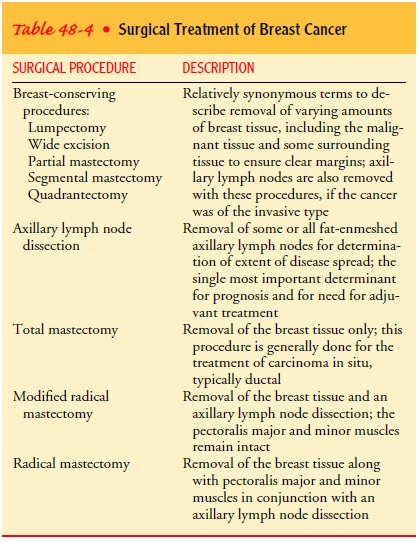

The main goal of surgical treatment is to eradicate the local pres-ence of the cancer. The procedures most often used for the local management of invasive breast cancer are mastectomy with or without reconstruction and breast-conserving surgery combined with radiation therapy. These procedures are described below. Surgical treatment options are summarized in Table 48-4. For pa-tients who undergo total mastectomy for the treatment of DCIS or as prophylactic surgery for the treatment for LCIS, the nursing care is similar to that of a modified radical mastectomy (described later in the text).

However, total mastectomy does not involve the removal

of axillary lymph nodes; therefore, mobility of the arm on the affected side is

regained much quicker, and there is no risk for lymphedema. Women still face

the same psychosocial issues involving the diagnosis of cancer and the loss of

the breast, and the nurse needs to address these in a similar manner.

Modified Radical Mastectomy.

Modified radical mastectomyisremoval of

the entire breast tissue, along with axillary lymph nodes. The pectoralis major

and pectoralis minor muscles remain intact. Before surgery, the surgeon plans

an incision that will pro-vide maximum opportunity to remove the tumor and the

affected nodes. At the same time, efforts are made to avoid a scar that will be

visible and restrictive. An objective of surgical treatment is to maintain or

restore normal function to the hand, arm, and shoul-der girdle on the affected

side. Skin flaps and tissue are handled with great care to ensure proper

viability, hemostasis, and drain-age. If reconstructive surgery is planned, a

consultation is made with a plastic surgeon before the mastectomy is performed.

After

the tumor is removed, bleeding points are ligated and the skin is closed over

the chest wall. Skin grafting is performed if the skin flaps are too small to

close the wound. A nonadherent dressing (Adaptic) may be applied and covered by

a pressure dress-ing. Two drainage tubes may be placed in the axilla and

beneath the superior skin flap, and portable suction devices may be used; these

remove the blood and lymph fluid that collect after surgery. The dressing may

be held in place by wide elastic bandages or a surgical bra.

Breast-Conserving Surgery.

Breast-conserving

surgery consistsof lumpectomy, wide excision, partial or segmental mastectomy,

or quadrantectomy (resection of the involved breast quadrant) and removal of

the axillary nodes (axillary lymph node dissection) for tumors with an invasive

component, followed by a course of radiation therapy to treat residual,

microscopic disease.

The

goal of breast conservation is to remove the tumor com-pletely with clear

margins while achieving an acceptable cosmetic result. The axillary lymph nodes

are also removed through a sep-arate semicircular incision under the hair-bearing

portion of the axilla. A drain is inserted into the axilla through a separate

stab wound to remove blood and lymph fluid. A dressing is applied over the

breast and under the arm and is secured with wide elas-tic bandages or a

surgical bra.

Survival

rates after breast-conserving surgery are equivalent to those after modified

radical mastectomy. The risk for local recur-rence, however, is greater, at 1%

per year after surgery (Winchester Cox, 1998). If the patient experiences a

local recurrence, stan-dard treatment is a completion or salvage mastectomy, in

which the rest of the breast tissue is removed. Survival rates after this

proce-dure are equivalent to those after mastectomy, but because the skin has

been irradiated, the choices for reconstruction remain lim-ited, and the woman

should be informed of this possibility at the time of diagnosis and when

considering her treatment options.

Postoperative Issues.

The

postoperative care of the patient un-dergoing a modified radical mastectomy or

breast-conserving surgery is similar because both procedures involve an

alteration to the breast and removal of lymph nodes from the axillary re-gion.

As with any surgical patient, the immediate focus is recov-ery from general

anesthesia and pain management. In addition, the patient who has had breast

surgery may experience both phys-ical and psychological effects. Possible

complications include the accumulation of blood (hematoma) at the incision

site, infection, and late accumulation of serosanguineous fluid (seroma) after

drain removal. Most patients who undergo breast surgery are dis-charged home

with a drainage collection device in place. The nurse teaches the patient and

family members to manage the drainage system.

Nerve

trauma with resultant phantom breast sensations, numb-ness, tingling, or

burning sensations may also occur and may per-sist for months or possibly years

after surgery. Impaired arm and shoulder mobility can result from the axillary

dissection. The dis-ruption of lymphatic and venous drainage can leave the

patient at risk for lymphedema

(chronic swelling of the affected extremity) at any point after surgery.

Psy-chological sequelae may include an altered body image or self-concept as a

result of the alteration or loss of the breast. Other major psychosocial

concerns include uncertainty about the fu-ture, fear of recurrence, and the

effects of breast cancer and its treatment on family and work roles.

Lymphatic Mapping and Sentinel Node Biopsy.

In the mid 1990s,a new procedure was introduced for use in patients

undergoing breast surgery for the treatment of invasive breast cancer.

Approx-imately 60% of patients who undergo an axillary lymph node dis-section

to determine the extent of the disease have negative nodes (Veronesi,

Galimberti, Zurrida et al., 2001). The use of lym-phatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy is changing the

waythese patients are treated because it provides the same prognostic

information as the axillary dissection. A radiocolloid and/or blue dye is

injected into the tumor site; the patient then undergoes the surgical

procedure. The surgeon uses a hand-held probe to locate the sentinel node (the

primary drainage site from the breast) and excises it, and it is examined by

the pathologist. If the sen-tinel node is negative for metastatic breast

cancer, a standard axil-lary dissection is not needed, thus sparing the patient

the sequelae of the procedure (surgical drain, altered mobility of the

extrem-ity, paresthesias, risk for lymphedema). If the sentinel node is

positive, the patient undergoes the standard axillary dissection. Reported

results of this technique suggest a success rate of more than 90% in correctly

identifying the sentinel node and correctly predicting axillary metastases

(Hsueh, Hansen & Guiliano, 2000), and many centers have incorporated this

procedure into standards

of care. Short-term follow-up demonstrates that the rate of lymphedema is

approximately 1% for women who undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Nursing

issues for this procedure focus on informing the pa-tient about the

expectations and possible implications. Because patients with a negative node

are spared the axillary dissection, they may be discharged home the same day.

Research is needed on the technique’s sequelae, however. Questions to be

addressed in-clude: Do patients experience similar sensations in the affected

arm as those who had an axillary dissection? Do patients demon-strate impaired

mobility? Do these patients develop axillary sero-mas after the procedure? What

is the risk for lymphedema? Initial nursing research on patient care issues

related to sentinel node biopsy demonstrates that women who have sentinel node

biopsy alone do have neuropathic sensations similar to those who undergo an

axillary dissection, although the prevalence, severity, and dis-tress are less

so (Baron, Fey, Raboy et al., 2002).

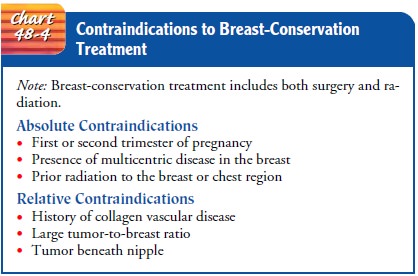

RADIATION THERAPY

With

breast-conserving surgery, a course of external-beam radia-tion therapy usually

follows excision of the tumor mass to de-crease the chance of local recurrence

and to eradicate any residual microscopic cancer cells. Radiation treatment is

necessary to ob-tain results equal to those of removal of the breast. If

radiation therapy is contraindicated, mastectomy is the patient’s only option

(Chart 48-4).

Radiation

treatment typically begins about 6 weeks after the surgery to allow the

incision to heal. If systemic chemotherapy is indicated, radiation therapy

usually begins after completion of the chemotherapy. External-beam irradiation

provided by a lin-ear accelerator using photons is delivered on a daily basis

over 5 to 7 weeks to the entire breast region. In addition, a concentrated

radiation dose or “boost” is administered to the primary site by means of

electrons. Before radiation therapy begins, the patient undergoes a planning

session for radiation treatment that will serve as the model for daily

treatments. Small permanent ink mark-ings are used to identify the breast

tissue to be irradiated. Patients need reassurance about the procedure and

self-care instructions related to side effects and their management.

Postoperative radiation after mastectomy is not common today but is still used in certain cases: when tumors have spread re-gionally (chest wall involvement, four or more positive nodes, or tumors larger than 5 cm). Occasionally, patients who have had a mastectomy require radiation treatment to the chest wall, gener-ally after completion of systemic chemotherapy. Treatment usu-ally consists of a course of external-beam irradiation to the area for a period of several weeks, but the time frame is determined by the radiation oncologist. Some studies suggest that survival may be enhanced for high-risk premenopausal women who receive chest wall irradiation after mastectomy.

Another

approach to radiation therapy is the use of intraoper-ative radiation therapy

(IORT), in which a single dose of radia-tion is delivered to the lumpectomy

site immediately after the surgeon has performed the lumpectomy. The dosage is

limited to the tumor area, as any errant cells are most likely to be within the

approximate area. The typical side effects of skin changes and fa-tigue are

minimized with this approach. It may be as effective as the standard 5- to

7-week radiation course, but long-term data are still needed to determine the

effect on local recurrence and survival rates.

Postirradiation Reaction.

Generally,

radiation therapy is welltolerated. Side effects are temporary and usually

consist of mild to moderate skin reaction and fatigue. Fatigue usually occurs

about 2 weeks after treatment and may last for several weeks after the

treatments are completed. Fatigue can be depressing, as can the frequent trips

to the radiation oncology unit or department for treatment. The patient needs

to be reassured that the fatigue is normal and not a sign of recurrence. Rare

complications of ra-diation therapy to the breast include pneumonitis, rib

fracture, and breast fibrosis.

Postirradiation Nursing Management.

Self-care

instructions forpatients receiving radiation are based on maintaining skin

in-tegrity during and after radiation therapy:

· Use mild soap with

minimal rubbing.

· Avoid perfumed soaps or

deodorants.

· Use hydrophilic lotions

(Lubriderm, Eucerin, Aquaphor) for dryness.

· Use a nondrying,

antipruritic soap (Aveeno) if itching occurs.

· Avoid tight clothes,

underwire bras, excessive temperatures, and ultraviolet light.

Patients

may note increased redness and, rarely, skin break-down at the booster site

(tissue site that received concentrated ra-diation). Important aspects of

follow-up care include teaching patients to minimize exposure of the treated

area to the sun for 1 year and reassurance that minor twinges and shooting pain

in the breast are normal reactions after radiation treatment.

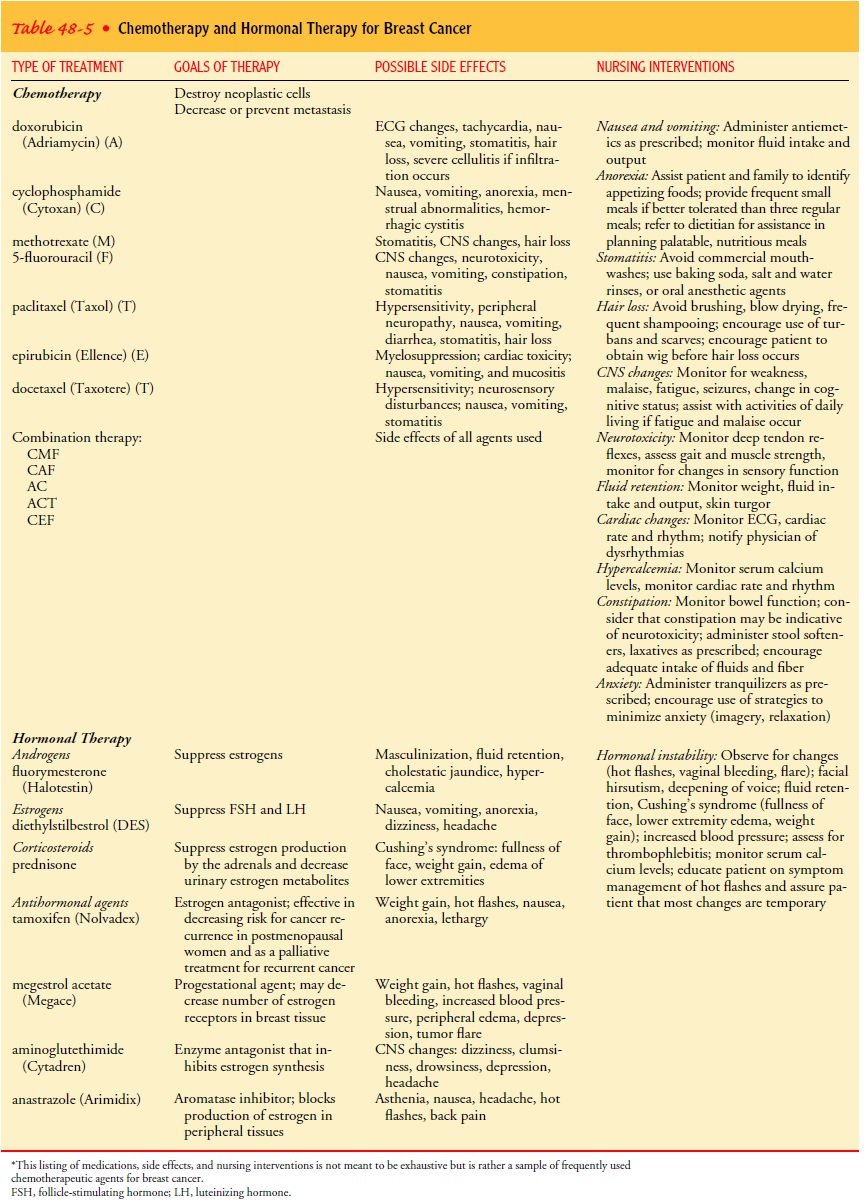

CHEMOTHERAPY

Chemotherapy

is administered to eradicate the micrometastatic spread of the disease.

Although chemotherapy is generally initiated after breast surgery, no single

standard exists for the sequencing of sys-temic chemotherapy and radiation

therapy. Ongoing clinical tri-als may help to determine which treatment

sequence produces the best outcomes.

Chemotherapy

regimens for breast cancer combine several agents to increase tumor cell

destruction and to minimize med-ication resistance. The chemotherapeutic agents

most often used in combination are cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) (C),

metho-trexate (M), fluorouracil (F), and doxorubicin (Adriamycin) (A).

Paclitaxel (Taxol) (T) has been recently introduced into the ad-juvant

chemotherapy setting, and the data from clinical trials suggest a slight

survival benefit with its use (Norton, 2001). Addi-tionally, a newer taxane,

docetaxel (Taxotere) (T), is being used more frequently, but research remains

limited on its difference. The combination regimen of CMF or CAF is a common

treatment protocol. AC, ACT (AC given first followed by T), and ATC, with all

three agents given together, are other regimens that may be used (Levine,

2001). A new anthracycline agent, epiru-bicin (Ellence), which has been used

more in Europe, is being used in certain regimens and protocols. Decisions

regarding the chemotherapeutic protocol are based on the patient’s age,

physi-cal status, and disease status and whether she is participating in a

clinical trial. Chemotherapy treatment modalities are summa-rized in Table

48-5.

Reactions to Chemotherapy.

Anticipatory

anxiety is a commonresponse among patients facing chemotherapy. Today, however,

side effects can be managed well, with many women continuing their daily work

and routine schedules. This has occurred in large measure because of the

meticulous educational and psychological preparation provided to patients and

their families by oncology nurses, oncologists, social workers, and other

members of the health care team. The other factor is the availability of medication

regimens that can alleviate the side effects of nausea and vomiting.

Common

physical side effects of chemotherapy for breast can-cer include nausea,

vomiting, taste changes, alopecia (hair loss), mucositis, dermatitis, fatigue,

weight gain, and bone marrow suppression. In addition, premenopausal women may

experience temporary or permanent amenorrhea leading to sterility.

Less

common side effects include hemorrhagic cystitis and conjunctivitis. Although

its cause is unknown, weight gain of more than 10 pounds occurs in about half

of all patients. Aero-bic exercise and its anxiety-alleviating effects may be

helpful to decrease weight gain and elevate mood. Side effects may vary with

the chemotherapeutic agent used. CMF is generally well tolerated with only

minimal side effects. Doxorubicin can be toxic to tis-sue if it infiltrates the

vein, so it is usually diluted and infused through a large vein. Nausea and

vomiting can occur. Antiemet-ics and tranquilizers may provide relief, as may

visual imagery and relaxation exercises. Doxorubicin and paclitaxel usually

cause alopecia, so obtaining a wig before hair loss occurs may prevent some of

the associated emotional trauma. The patient needs re-assurance that new hair

will grow when treatment is completed, although the color and texture of the

hair may differ. It is help-ful to provide a list of wig suppliers in the

patient’s geographic region and to become familiar with creative ways to use

scarves and turbans to reduce the patient’s reactions to hair loss. The

American Cancer Society offers a program called “Look Good, Feel Better” that

provides useful tips for applying cosmetics during chemotherapy.

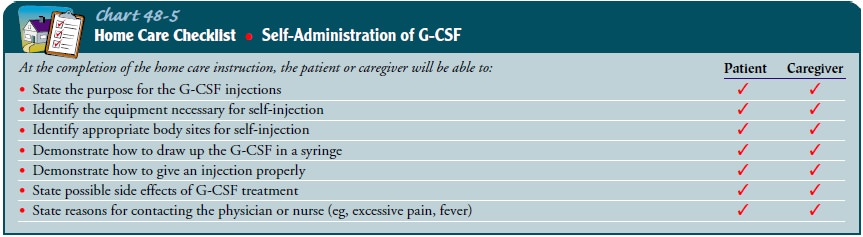

Nursing Management in Chemotherapy.

Nurses

working withpatients receiving chemotherapy play an important role in

assist-ing those who have difficulty with the side effects of treatment.

Encouraging the use of medications to limit nausea, vomiting, and mouth sores

reduces discomfort during chemotherapy. Some pa-tients may receive granulocyte

colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), synthetic growth-stimulating factor injected

subcutaneously daily for 10 days, which boosts the white blood cell count to

pre-vent nadir fever (a fever that occurs with infection when the blood cell

counts are at their lowest level) and infections. The nurse in-structs the

patient and family on injection technique and about symptoms that require

follow-up with a physician (Chart 48-5).

Taking time to explain side effects and possible solutions may alleviate some of the anxiety of women who feel uncom-fortable asking questions. The more informed a patient is about the side effects of chemotherapy and how to manage them, the better she can anticipate and deal with them Chemotherapy may negatively affect the patient’s self-esteem, sexuality, and sense of well-being. Combined with the stress of a potentially life-threatening diagnosis, these changes can be over-whelming.

Because many women are

distressed by financial con-cerns and time spent away from the family, nursing

support and teaching can reduce emotional distress during treatment. Important

aspects of nursing care include communicating, facilitating support groups,

encouraging patients to ask questions, and promoting trust in health care

providers. Adequate time must be scheduled for clin-ical appointments to allow

discussion and questions. Most women with breast cancer today are treated in a

multidisciplinary environ-ment, and referrals to the dietitian, social worker,

psychiatrist, or spiritual advisor can assist in dealing with many of the

issues of cancer treatment. In addition, numerous community supports and

advocacy groups are available to these patients and their families.

HORMONAL THERAPY

Decisions about hormonal therapy for breast cancer are based on the outcome of an estrogen and progesterone receptor assay of tumor tissue taken during the initial biopsy. The tissue requires special handling by laboratory technicians with expertise in assess-ment techniques. Normal breast tissue contains receptor sites for estrogen. About two thirds of breast cancers are estrogen depen-dent, or ER-positive (ER+). An ER+ assay indicates that tumor growth depends on estrogen supply; therefore, measures that re-duce hormone production may limit the progression of the disease, and these receptors can be considered prognostic indicators. ER+ tumors may grow more slowly in general than those that do not depend on estrogen (ER−); thus, having an ER+ tumor indicates a better prognosis. A value less than 3 fmol/mg is considered neg-ative. Values of 3 to 10 are questionable, and values greater than 10 are considered positive.

The greater the value, the more bene-ficial the

anticipated effect from hormone suppression can be. Patients with tumors that

are positive for both estrogen and progesterone (PR+) generally have a more

favorable prognosis than patients with tumors that are ER− and

PR−. Most progesterone-receptive tumors also have a

positive estrogen receptor status. The loss of progesterone receptors can be a

sign of advancing disease. Premenopausal women and perimenopausal women are

more likely to have non–hormone-dependent lesions; postmenopausal women are

likely to have hormone-dependent lesions.

Hormonal

therapy may include surgery to remove endocrine glands (eg, the ovaries,

pituitary, or adrenal glands) with the goal of suppressing hormone secretion.

Oophorectomy (removal of the ovaries) is one treatment option for premenopausal

women with estrogen-dependent tumors. Tamoxifen is the primary hor-monal agent

used in breast cancer treatment today. Anastrazole (Arimidex), letrozole

(Femara), leuprolide (Lupron), megestrol (Megace), diethylstilbestrol (DES),

fluoxymesterone (Halotestin), and aminoglutethimide (Cytadren) are other

hormonal agents used to suppress hormone-dependent tumors. Most of these agents

may be associated with menopausal symptoms such as vasomotor changes.

Hypercalcemia may also occur and may necessitate dis-continuing the agent.

These hormonal agents are described in Table 48-5.

BONE MARROW TRANSPLANTATION

Bone

marrow transplantation (BMT) involves removing bone marrow from the patient and

then administering high-dose chemotherapy. The patient’s bone marrow, spared

from the ef-fects of chemotherapy, is then reinfused intravenously. This

pro-cedure is usually performed in specialized transplantation centers, and

specific patient preparation, education, and support must be given throughout

the treatment course. In 1999, scientific mis-conduct was discovered in the

only study that showed a benefit (Hagmann, 2000), casting doubt on the role

that BMT may play in breast cancer treatment. The use remains controversial

outside of clinical trials, since studies are not clear as to the true benefits

in comparison to standard high-dose chemotherapy (Antman, 2001).

INVESTIGATIONAL THERAPY: THE FUTURE

Research

is underway to develop chemotherapeutic agents that modify multidrug resistance

and agents that enhance or modify standard chemotherapy. Research in breast

cancer treatment in-cludes the following areas: peripheral stem cell

transplants, on-cogenes (tumor genes that control cell growth), growth factors

(substances released by cancer cells to make the environment more conducive to

growth), monoclonal antibodies (synthetic antibodies that fight cancer cells),

biologic response modifiers (substances that help increase the body’s immune

system response), and vaccine studies.

Another

treatment modality that has shown promise is trastuzumab (Herceptin). This

monoclonal antibody was engi-neered from mouse antibodies and closely resembles

a human antibody. Herceptin binds with the HER2 protein, and this pro-tein

regulates cell growth, thus inhibiting tumor cell growth. For women with

metastatic breast cancer, about 25% to 30% of tu-mors overproduce HER2, and

this monoclonal antibody can slow growth and possibly stimulate the immune

response. In fall 1998, the FDA approved this agent for the treatment of

metastatic breast cancer. Research is ongoing, but the addition of this agent

to traditional chemotherapy has shown improved survival rates in clinical

trials (Capriotti, 2001). Further research and clinical experience will

demonstrate the potential of this drug in the treat-ment of breast cancer,

particularly on the role of Herceptin for women undergoing adjuvant therapy.

Related Topics