Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Breast Disorders

Assessment of Patients With Breast Disorders

Assessment

HEALTH HISTORY AND CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

When

assessing a patient who describes a breast problem, the nurse should ask the

woman when she noted the problem and how long it has been present. Other

questions include: Is pain as-sociated with the symptom, and can you feel any

areas in your breast that are of concern? What are your breast self-examination (BSE) practices? Have you had a mammogram

or any other screening or diagnostic tests? If so, when? What follow-up

rec-ommendations were made?

The

woman is asked about her reproductive history because of its relationship to

risk for breast disorders. Questions should include the woman’s age at

menarche, last menstrual period, cycle regularity, and use of oral

contraceptives or other hormone prod-ucts. Other necessary information includes

her history of preg-nancies, live births, abortions, or miscarriages, and

breastfeeding. If the patient is postmenopausal, her age at menopause and any

symptoms she experienced and current or previous use of hor-mone replacement

therapy are also addressed.

General

health assessment includes the patient’s use of to-bacco and alcohol. Her

medical and surgical history is important to obtain, along with any family

history of diseases, particularly cancer. Social information, such as marital

status, occupation, and the availability of resources and support persons,

should also be elicited.

Psychosocial Implications of Breast Disease

Because

of the significant role of the breast in a woman’s sexual-ity, responses to any

actual or suspected disease may include fear, anxiety, and depression. Specific

responses may include fears of disfigurement, loss of sexual attractiveness,

abandonment by her partner, and death. These fears may cause some women to

delay seeking health care for evaluation of a possible breast problem.

Alternatively, in some women anxiety or fear regarding breast cancer may cause

them to seek the services of a health care pro-vider for the slightest change

or problem.

In

response to these reactions, the nurse’s role is to identify the patient’s

concerns, anxieties, and fears. Patient education and psychosocial support

become key nursing interventions. Assess-ment of the woman’s concerns related

to breast care and her re-sponses to a potential problem is important whether

the problem is benign or potentially malignant. Nurses can help women through

the potentially frightening visit to the primary health care provider or

surgeon. Because of underlying fears about a breast problem, anxiety management

is a valuable intervention, and the nurse’s calm, caring demeanor, along with astute

listen-ing skills and concrete direction and guidance, can decrease a woman’s

anxiety during the process.

PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT: FEMALE BREAST

Examination of the female breast can be conducted during any general physical or gynecologic examination or whenever the pa-tient suspects, reports, or fears breast disease. A clinical breast ex-amination is recommended at least every 3 years for women ages 20 to 40 years, and then annually. A thorough breast examina-tion, including instruction in BSE, takes at least 10 minutes.

Inspection

Examination

begins with inspection. The patient disrobes to the waist and sits in a

comfortable position facing the examiner. The breasts are inspected for size

and symmetry. A slight variation in the size of each breast is common and

generally normal. The skin is inspected for color, venous pattern, and

thickening or edema. Erythema (redness) may indicate benign local inflammation

or superficial lymphatic invasion by a neoplasm. A prominent venous pattern can

signal increased blood supply required by a tumor. Edema and pitting of the

skin may result from a neo-plasm blocking lymphatic drainage and giving the

skin an orange-peel appearance (peau d’orange), a classic sign of advanced

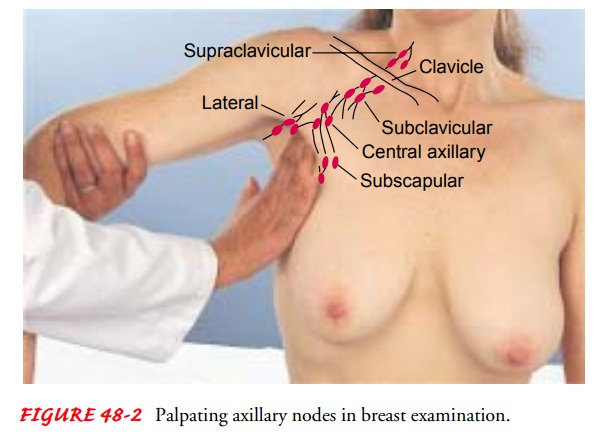

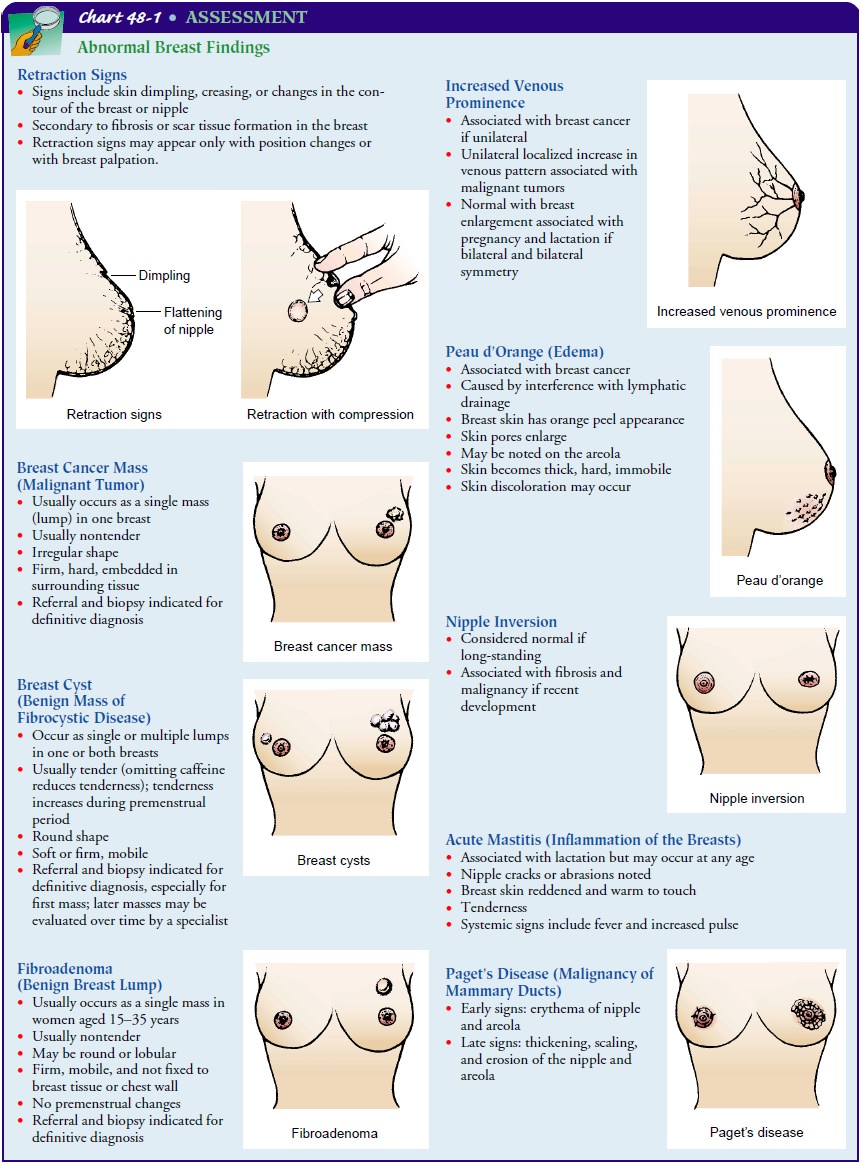

breast cancer. Examples of abnormal breast findings can be found in Chart 48-1.

Although

the appearance of the nipple–areola complex varies greatly between patients,

for individual women the two are gen-erally similar in size and shape.

Inversion of one or both is not un-common and is a significant finding only

when of recent origin. Ulceration, rashes, or spontaneous nipple discharge

requires eval-uation. To elicit a dimpling or retraction that may otherwise go

undetected, the examiner instructs the patient to raise both arms overhead.

This maneuver normally elevates both breasts equally. Next, the patient is

instructed to place her hands at her waist and push in. These movements,

causing contraction of the pectoral muscles, do not normally alter the breast

contour or nipple di-rection. Any dimpling or retraction during these position

changes may suggest a potential malignancy. The clavicular and axillary regions

are inspected for swelling, discoloration, lesions, or en-larged lymph nodes.

Palpation

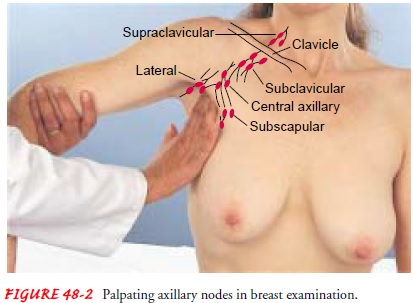

Palpation

of the axillary and clavicular areas is easily performed with the patient

seated. To examine the axillary lymph nodes, the examiner gently abducts the

patient’s arm from the thorax. The pa-tient’s left forearm is grasped gently

and supported with the exam-iner’s left hand. The right hand is then free to

palpate the axillae and note any lymph nodes that may be lying against the

tho-racic wall. The flat parts of the fingertips are used to gently pal-pate

the areas of the central, lateral, subscapular, and pectoral nodes (Fig. 48-2).

Normally, these lymph nodes are not palpa-ble, but if they are enlarged, their

size, location, mobility, con-sistency, and tenderness are noted. The breasts

are also palpated with the patient sitting in an upright position.

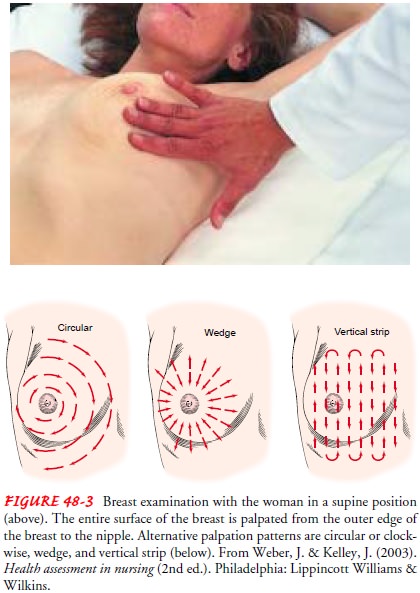

The

patient is then assisted to a supine position. Before the breast is palpated,

the patient’s shoulder is elevated by a small pillow to balance the breast on

the chest wall. Failure to do this allows the breast tissue to slip laterally,

and a breast mass may be missed in this thickened tissue. Light, systematic

palpation in-cludes the entire surface of the breast and the axillary tail. The

examiner may choose to proceed in a clockwise direction, fol-lowing imaginary

concentric circles from the outer limits of the breast toward the nipple. Other

acceptable methods are to pal-pate from each number on the face of the clock

toward the nip-ple in a clockwise fashion or along imaginary vertical lines on

the breast (Fig. 48-3).

During

palpation, the examiner notes tissue consistency, patient-reported tenderness,

or masses. If a mass is detected, it is described by its location (eg, left

breast, 2 cm from the nipple at 2 o’clock position). Size, shape, consistency,

border delineation, and mobility are included in the description. Finally, the

areola is gently compressed to detect any discharge or secretion.

The breast tissue of the adolescent is usually firm and lobular, whereas that of the postmenopausal woman is more likely to feel thinner and more granular. During pregnancy and lactation, the breasts are firmer and larger, with lobules that are more distinct. Hormonal changes cause the areola to darken.

Cysts are commonly

found in menstruating women and are usually well de-fined and freely movable.

Premenstrually, cysts may be larger and more tender. Malignant tumors, on the

other hand, tend to be hard, the consistency of a pencil eraser, poorly

defined, fixed to the skin or underlying tissue, and usually nontender. A

physician should evaluate any abnormalities detected during inspection and

palpation.

PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT: MALE BREAST

Because

breast cancer can occur in men, examination of the male breast and axillae is

an important part of physical assessment. The nipple and areola are inspected

for masses. Most cancers in men are found at a later stage, possibly because

men are not aware of their risk for developing breast cancer. Treatment of

breast can-cer in males is similar as well.

Gynecomastia (overdeveloped mammary glands in the male)is

differentiated from the soft, fatty enlargement of obesity by the firm

enlargement of glandular tissue beneath and immediately surrounding the areola.

The same procedure for palpating the female axillae is used when assessing the

male axillae.

Related Topics