Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Breast Disorders

Breast Cancer

Breast Cancer

There

is no single, specific cause of breast cancer; rather, a com-bination of

hormonal, genetic, and possibly environmental events may contribute to its

development.

Etiology

Hormones

produced by the ovaries have an important role in breast cancer. Two key

ovarian hormones, estradiol and proges-terone, are altered in the cellular

environment by a variety of fac-tors, and these may affect growth factors for

breast cancer.

HORMONES

The

role of hormones and their relationship to breast cancer re-main controversial.

Research suggests that a relationship exists between estrogen exposure and the

development of breast can-cer. In laboratory studies, tumors grow much faster

when ex-posed to estrogen, and epidemiologic research suggests that women who

have longer exposure to estrogen have a higher risk for breast cancer. Early

menarche, nulliparity, childbirth after 30 years of age, and late menopause are

known but minor risk factors. The assumption is that these factors are all

associated with prolonged exposure to estrogen because of menstruation. The

theory is that each cycle (which has high levels of endoge-nous estrogen)

provides the cells of the breast another chance to mutate, increasing the

chance for cancer to develop. Estrogen itself does not cause breast cancer, but

it is associated with its development.

GENETICS

Growing

evidence indicates that genetic alterations are associated with the development

of breast cancer. These genetic alterations include changes or mutations in

normal genes and the influence of proteins that either promote or suppress the

development of breast cancer. Genetic alterations may be somatic (acquired) or

germline (inherited). To date, two gene mutations have been iden-tified that

may play a role in the development of breast cancer. A mutation in the BRCA-1 gene has been linked to the

develop-ment of breast and ovarian cancer, whereas a mutation in the BRCA-2 gene identifies risk for breast

cancer, but less so for ovar-ian cancer (Houshmand, Campbell, Briggs et al.,

2000). These gene mutations may also play a role in the development of colon,

prostate, and pancreatic cancer, but this is far from clear at pres-ent. It has

been estimated that 1 of 600 women in the general population has either a

BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 gene mutation. For women who carry either mutation, the risk

for developing breast cancer can range from 50% to 90% (Kauff, Satagopan,

Robson et al., 2002).

At

present, only 5% to 10% of all breast cancers are estimated to be associated

with the BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 gene mutations. It is thought, however, that breast

cancer is genetic and that up to 80% of women diagnosed with breast cancer

before age 50 years have a genetic component to their disease (Boyd, 1996).

This is believed to be linked to either unidentified BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 carriers

or less penetrating genes that have yet to be identified through genetics

research. A woman’s risk for either BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 should be interpreted with

caution and with an exhaus-tive look at all her other risk factors; this is

usually carried out by a genetics counselor.

Abnormalities

in either of the two genes can be identified by a blood test; however, women

should be counseled about the risks and benefits before actually undergoing

genetic testing. The risks and benefits of a positive or negative result should

be explored. Treatment options for a positive result are long-term

surveillance, bilateral prophylactic mastectomy, or chemoprevention with

ta-moxifen, as discussed previously. A positive result can cause tremendous

anxiety and fear, can unleash potential discrimina-tion in employment and

insurability, and can cause a woman to search for answers that may not be

available. A negative result can produce survivor guilt in a person with a

strong family history of cancer. For these women, the risk for breast cancer is

similar to that of the general population, and routine screening guidelines

should be followed. The decision to pursue genetic testing must be made

carefully, and women should be asked what they will do differently after they

know the results. Furthermore, because testing is relatively new and health

care providers have yet to de-termine a true benefit from a positive or

negative result, genetic testing should be done under the auspices of clinical

research pro-tocols to protect the patient (because these data are kept

separate from the patient’s medical record). Nurses play a role in educat-ing

patients and their family members about the implications of genetic testing.

Ethical issues related to genetic testing include possible employment

discrimination, bias in insurability and pos-sibly with insurance rates, and

family members’ concerns (eg, effect on siblings, children).

Risk Factors

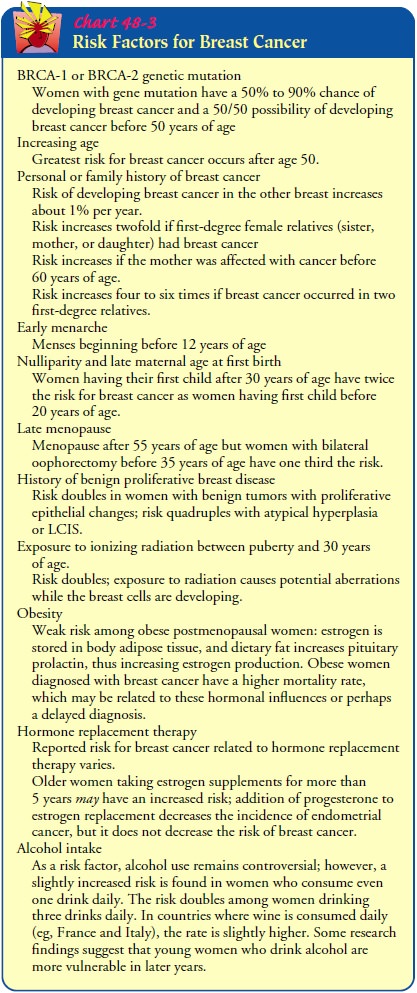

Although

there are no specific known causes of breast cancer, re-searchers have

identified a cluster of risk factors (Chart 48-3). These factors are important

in helping to develop prevention pro-grams. However, nearly 60% of women

diagnosed with breast cancer have no identifiable risk factors other than their

hormonal environment (Vogel, 2000). Thus, all women are considered at risk for

developing breast cancer during their lifetime. Nonethe-less, identifying risk

factors provides a means for identifying women who may benefit from increased

surveillance and early treatment. In addition, further research into risk

factors will help in developing strategies to prevent or modify breast cancer

in the future.

A

high-fat diet was once thought to increase the risk of breast cancer.

Epidemiologic studies of American and Japanese women showed that American women

had a fivefold higher rate of breast cancer. Japanese women who moved to the

United States were shown to have breast cancer rates similar to their Caucasian

counterparts. Recent cohort studies show only weak or incon-clusive relationships

between a high-fat diet and breast cancer (Brown et al., 2001). Because fat

intake is implicated in colon cancer and heart disease, however, women may

benefit from lowering their intake of fat.

Oral

contraceptives were once thought to increase the risk for breast cancer.

Currently, no association is thought to exist in women in the general

population, but there are no data about the effect on women considered to be at

high risk.

The

role of smoking in breast cancer remains unclear. Most studies suggest that

smoking does not increase a woman’s risk for breast cancer. Some studies,

however, suggest that smoking does increase the risk for breast cancer and that

the earlier a woman be-gins smoking, the higher her risk. Smoking does increase

the risk for lung cancer, which is the leading cause of death in women with

cancer (breast cancer is second). Smoking cessation is part of a healthy

lifestyle, and nurses have a key role in providing women with information about

smoking cessation programs.

Silicone

breast implants can be associated with fibrous capsu-lar contraction, and some

women and medical professionals have claimed an association with certain immune

disorders. There is no evidence, however, that breast implants are associated

with an increased risk of breast cancer.

Protective Factors

Certain factors may be protective in relation to the development of breast cancer. Regular, vigorous exercise has been shown to de-crease risk, perhaps because it can delay menarche, suppress men-struation, and, like pregnancy, reduce the number of ovulatory menstrual cycles. Also, exercise decreases body fat, where estro-gens are stored and produced from other steroid hormones. Thus, decreased body fat can decrease extended exposure to estrogen.

Breastfeeding

is also thought to decrease risk because it prevents the return of

menstruation, again decreasing exposure to endo-genous estrogen. Having had a

full-term pregnancy before the age of 30 years is also thought to be

protective. Protective hormones are released after delivery of the fetus, with

the purpose of revert-ing to normal the proliferation of cells in the breast

that occur with pregnancy.

Clinical Manifestations

Breast

cancers occur anywhere in the breast, but most are found in the upper outer

quadrant, where most breast tissue is located. Generally, the lesions are

nontender rather than painful, fixed rather than mobile, and hard with

irregular borders rather than encapsulated and smooth. Complaints of diffuse

breast pain and tenderness with menstruation are usually associated with benign

breast disease. Marked pain at presentation, however, may be associated with

breast cancer in the later stages.

With

the increased use of mammography, more women are seeking treatment at an earlier

stage of disease. These women may have no symptoms and no palpable lump, but

abnormal lesions are detected on mammography. Unfortunately, many women with

advanced disease seek initial treatment only after ignoring symptoms. For

example, they may seek attention for dimpling or for a peau d’orange

(orange-peel) appearance of the skin (a condi-tion caused by swelling that

results from obstructed lymphatic cir-culation in the dermal layer). Nipple

retraction and lesions fixed to the chest wall may also be evident. Involvement

of the skin is manifested by ulcerating and fungating lesions. These classic

signs and symptoms characterize breast cancer in the late stages. A high index

of suspicion should be maintained with any breast abnor-mality, and abnormalities

should be promptly evaluated.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Techniques

to determine the histology and tissue diagnosis of breast cancer include FNA,

excisional (or open) biopsy, incisional biopsy, needle localization, core

biopsy, and stereotactic biopsy (all described previously). In addition to the

staging criteria de-scribed below, other pathologic features and prognostic

tests are used to identify different patient groups that may benefit from

adjuvant treatment. Histologic examination of the cancer cells helps determine

the prognosis and leads to a better understand-ing of how the disease

progresses.

Breast Cancer Staging

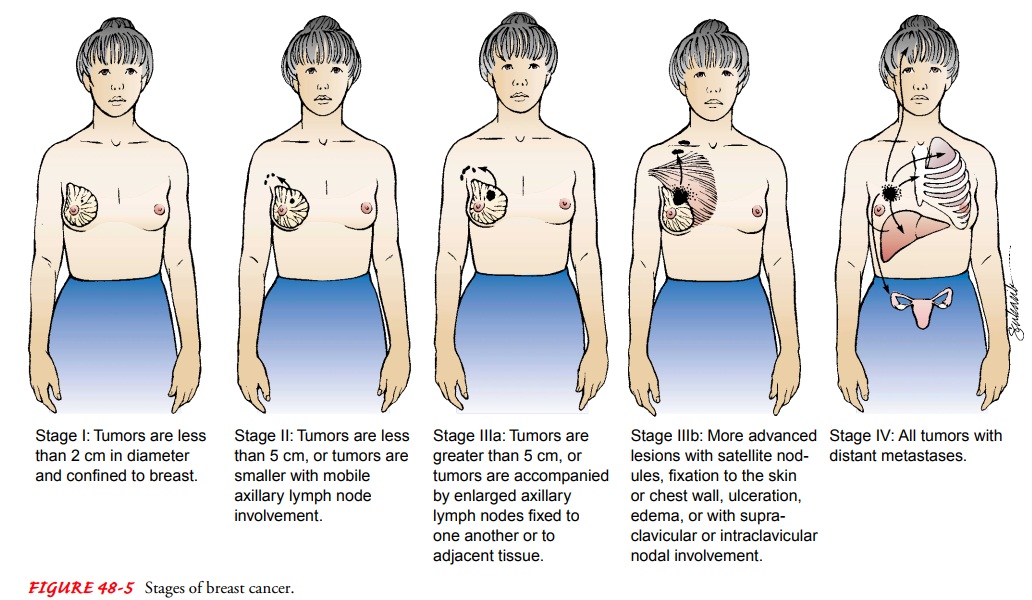

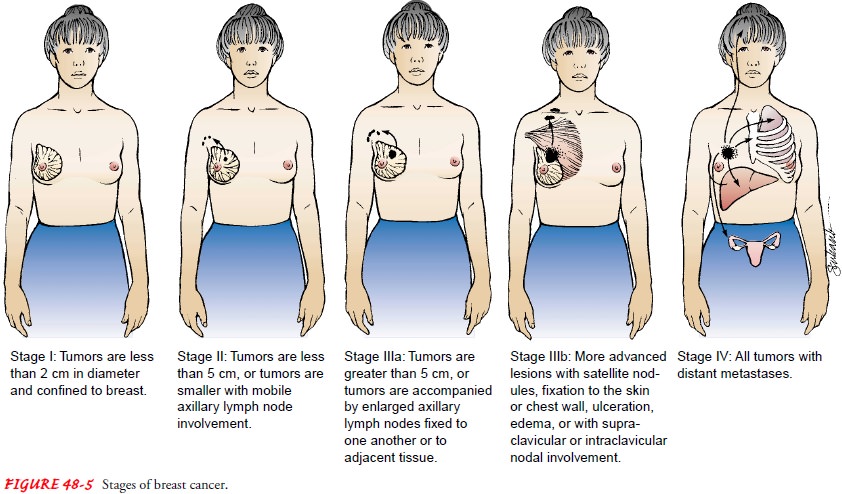

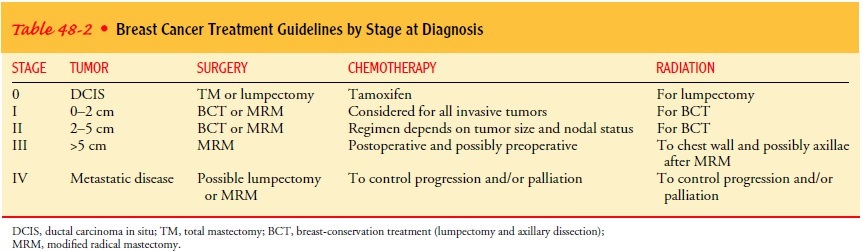

Staging

involves classifying the cancer by the extent of disease (see Fig. 48-5).

Staging of any cancer is important because it helps the health care team

identify and recommend the best treatment available, offer a prognosis, and

compare the results of various treatment regimens. Several diagnostic tests and

procedures are performed in the staging of the disease. These may include chest

x-rays, bone scans, and liver function tests. Clinical staging in-volves the

physician’s estimate of the size of the breast tumor and the extent of axillary

node involvement by physical examination (palpable nodes may indicate

progression of the disease) and mammography. After the diagnostic workup and

the definitive surgical treatment, the breast cancer is staged according to the

TNM system (Greene, Page, Fleming, et al., 2002), which evaluates the size of

the tumor, number of nodes involved, and evidence of dis-tant metastasis.

Pathologic staging based on histology provides information for a more accurate

prognosis. Table 48-2 lists typi-cal treatment guidelines by stage at

diagnosis.

Prognosis

Several features of breast tumors contribute to the prognosis. Generally, the smaller the tumor, the better the prognosis. Car-cinoma of the breast is not a pathologic entity that develops overnight. It starts with a genetic alteration in a single cell. It can take about 16 doubling times for a carcinoma to become 1 cm or larger, at which point it becomes clinically apparent. Assuming that it takes at least 30 days for each doubling time, it would take a minimum of 2 years for a carcinoma to become palpable. This concept is important for nurses in teaching and counseling pa-tients because once breast cancer is diagnosed, women have a safe period of several weeks to make a decision regarding treatment.

The

prognosis also depends on whether the cancer has spread. For example, the

overall 5-year survival rate is greater than 98% when the tumor is confined to

the breast (ACS, 2002). When the cancer cells have spread to the regional lymph

nodes, however, the overall 5-year survival rate falls to 76%. The 5-year

survival rate for women diagnosed with metastatic disease is 16%. At

diagno-sis, about 37% of patients have evidence of regional or distant spread

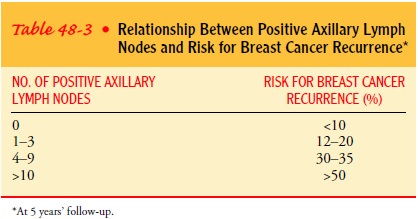

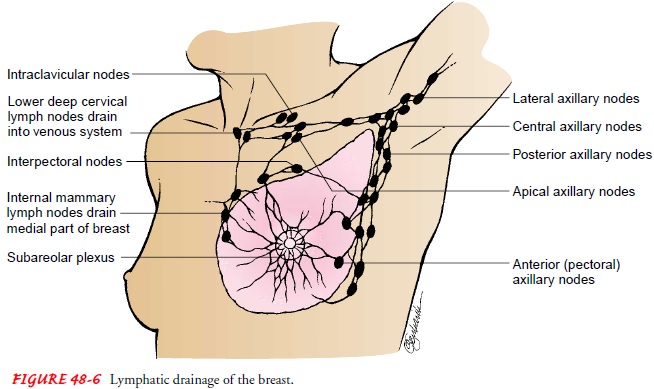

or metastasis. The most common route of regional spread is to the axillary

lymph nodes. Table 48-3 describes the relation-ship between positive axillary

lymph nodes and the risk for breast cancer recurrence. Other sites of lymphatic

spread include the in-ternal mammary and supraclavicular nodes (Fig. 48-6).

Distant metastasis can affect any organ, but the most common sites are bone

(71%), lung (69%), liver (65%), pleura (51%), adrenals (49%), skin (30%), and

brain (20%) (Winchester & Cox, 1998).

In addition to tumor size, nodal involvement, evidence of metastasis, and histologic type, other measures help in determin-ing prognosis. The presence of estrogen and progesterone recep-tor proteins indicates retention of regulatory controls of the mammary epithelium. The presence of both receptor proteins is associated with an improved prognosis; their absence is associated with a poorer prognosis. Similarly, a tumor with a high degree of differentiation is associated with a better prognosis than a poorly differentiated anaplastic tumor. The assessment of a tumor’s pro-liferative rate (S-phase fraction) and DNA content (ploidy) by lab-oratory assay may help to determine prognosis because these two factors are strongly correlated with other prognostic factors, and research is ongoing to examine how helpful these two factors may actually be. Tumors classified as diploid (normal DNA content) are associated with a better prognosis than are tumors classified as aneuploid (abnormal DNA content).

Related Topics