Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Delirium and Dementia

Dementia, Delirium and Other Cognitive Disorders

Dementia, Delirium and Other

Cognitive Disorders

Dementia

Dementia is defined in DSM-IV as a series of

disorders character-ized by the development of multiple cognitive deficits

(including memory impairment) that are due to the direct physiological effects

of a general medical condition, the persisting effects of a substance, or

multiple etiologies (e.g., the combined effects of a metabolic and a

degenerative disorder) (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The disorders

constituting the dementias share a common symptom presentation and are

identified and classified on the basis of etiology. The cognitive deficits

exhibited in these disorders must be of significant severity to interfere with

either occupational functioning or the individual’s usual social activities or

relationships. In addition, the observed deficits must represent a decline from

a higher level of function and not be the consequence of a delirium. A delirium

can be superimposed on a dementia, however, and both can be diagnosed if the

dementia is observed when the delirium is not in evidence. Dementia typically

is chronic and occurs in the presence of a clear sensorium. If clouding of

con-sciousness occurs, the diagnosis of delirium should be considered. The

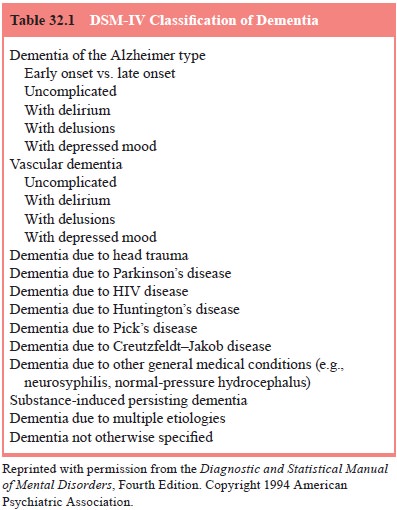

DSM-IV classification of dementia is reviewed in Table 32.1.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of dementias is not precisely known.

Estimates vary depending on the age range of the population studied and whether

the individuals sampled were in the general community, acute care facilities,

or long-term nursing institutions. A review of 47 sur-veys of dementia

conducted between 1934 and 1985 indicated that the prevalence of dementia

increased exponentially by age, dou-bling every 5 years up to age 95 years, and

that this condition was equally distributed among men and women, with

Alzheimer’s de-mentia (AD) much more common in women (Slaby and Erle, 1993). A

National Institute of Mental Health Multisite Epidemiological Catchment Area

study revealed a 6-month prevalence rate for mild dementia of 11.5 to 18.4% for

persons older than 65 years living in the community (Kallmann, 1989). The rate

for severe dementia was higher for the institutionalized elderly: 15% of the

elderly in retirement communities, 30% of nursing home residents and 54% of the

elderly in state hospitals (Cummings and Benson, 1983).

Studies suggest that the fastest growing segment of the US population consists of persons older than the age of 85 years, 15% of whom are demented (Henderson, 1990). Half of the US population currently lives to the age of 75 years and one quarter lives to the age of 85 (Berg et al., 1994). A study of 2000 con-secutive admissions to a general medical hospital revealed that 9% were demented and, among those, 41% were also delirious on admission (Erkinjuntii et al., 1986). The cost of providing care for demented patients exceeds $100 billion annually (about 10% of all health care expenditures), and the average cost to families in 1990 was $18 000 a year (Berg et al., 1994

Clinical Features

Essential to the diagnosis of dementia is the

presence of cognitive deficits that include memory impairment and at least one

of the following abnormalities of cognition: aphasia, agnosia, apraxia, or a

disturbance in executive function (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

Memory function is divided into three compartments that can easily be evaluated

during a mental status examination. These are immediate recall (primary

memory), recent (secondary) memory and remote (tertiary) memory. Primary memory

is characterized by a limited capacity, rapid accessibility and a duration of

seconds to a minute (Karp, 1984). The anatomic site of destruction of primary

memory is the reticular activating system, and the principal activity of the

primary memory is the registration of new information. Primary memory is

generally tested by asking the individual to repeat immediately a series of

numbers in the order given. For instance, if the examiner mentions the numbers

1–2–3, the patient should be able to repeat them in the same order. This loss

of ability to register new information accounts in part for the confusion and

frustration the demented patient feels when confronted with unexpected changes

in daily routine. Secondary memory has a much larger capacity than primary

memory, a duration of minutes to years, and relatively slow accessibility. The

anatomic site of dysfunction for secondary memory is the limbic system, and

individuals with a lesion in this area may have little difficulty repeating

digits immediately, but show rapid decay of these new memories. In minutes, the

patient with limbic involvement may be totally unable to recall the digits or

even remember that a test has been administered (Karp, 1984). Thus, secondary

memory represents the retention and recall of information that has been

previously registered by primary memory. Clinically, secondary memory is tested

by having the individual repeat three objects afterhaving been distracted

(usually by the examiner’s continuation of the Mental Status Examination) for 3

to 5 minutes. Like primary memory, secondary recall is often impaired in

dementia. Often if the examiner gives the demented patient a clue (such as “one

of the objects you missed was a color”), the patient correctly identifies the

object. If this occurs the memory testing should be scored as “three out of

three with a cue”, which is considered to be a slight impairment. Giving clues

to the demented patient with a primary memory loss is pointless, because the

memories were never registered. Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome is an example of a

condition in which primary memory may be intact while secondary recall is

impaired.

Tertiary (remote) memory has a capacity that is

probably unlimited, and such memories are often permanently retained. Access to

tertiary memories is slow, and the anatomical dys-function in tertiary memory

loss is in the association cortex (Karp, 1984). In the early stages of

dementia, tertiary memory is generally intact. It is tested by instructing the

individual to remember personal information or past material. The personal

significance of the information often influences the patient’s abil-ity to

remember it. For example, a woman who worked for many years as a seamstress

might remember many details related to that occupation, but could not recall

the names of past presidents or three large cities in the USA. Thus, a

patient’s inability to re-member highly significant past material is an ominous

finding. Collateral data from informants is essential in the proper assess-ment

of memory function. In summary, primary and secondary memories are most likely

to be impaired in dementia, with terti-ary memory often spared until late in

the course of the disease.

In addition to defects in memory, patients with

dementia often exhibit impairments in language, recognition, object nam-ing and

motor skills. Aphasia is an abnormality of language that often occurs in

vascular dementias involving the dominant hemi-sphere. Because this hemisphere

controls verbal, written and sign language, these patients may have significant

problems interact-ing with people in their environment. Patients with dementia

and aphasia may exhibit paucity of speech, poor articulation and a telegraphic

pattern of speech (nonfluent, Broca’s aphasia). This form of aphasia generally

involves the middle cerebral artery with resultant paresis of the right arm and

lower face. Despite faulty communication skills, patients having dementia with

non-fluent aphasia have normal comprehension and awareness of their language

impairment. As a result, such patients often present with significant

depression, anxiety and frustration.

By contrast, patients having dementia with fluent

(Wernicke’s) aphasia may be quite verbose and articulate, but much of the

language is nonsensical and rife with such parap-hasias as neologisms and clang

(rhyming) associations. Whereas nonfluent aphasias are usually associated with

discrete lesions, fluent aphasia can result from such diffuse conditions as

demen-tia of the Alzheimer type. More commonly, fluent aphasias oc-cur in

conjunction with vascular dementia secondary to temporal or parietal lobe CVA.

Because the demented patients with fluent aphasia have impaired comprehension,

they may seem apathetic and unconcerned with their language deficits if they

are, in fact, aware of them at all. They do not generally display the

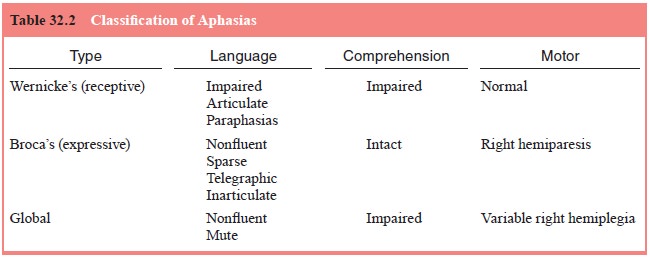

emo-tional distress of patients with dementia and nonfluent aphasia (Table

32.2).

Patients with dementia may also lose their ability

to rec-ognize. Agnosia is a feature of a dominant hemisphere lesion and

involves altered perception in which, despite normal sensations, intellect and

language, the patient cannot recognize objects. This

is in contrast to aphasia in which the patient with

dementia may not be able to name objects, but can recognize them. The type of

agnosia depends on the area of the sensory cortex that is in-volved. Some

demented patients with severe visual agnosia can-not name objects presented,

match them to samples, or point to objects named by the examiner. Other patients

may present with auditory agnosia and be unable to localize or distinguish such

sounds as the ringing of a telephone. A minority of demented patients may

exhibit astereognosis, inability to identify an ob-ject by palpation. Demented

patients may also lose their ability to carry out selected motor activities

despite intact motor abili-ties, sensory function and comprehension of the

assigned task (apraxia). Affected patients cannot perform such activities as

brushing their teeth, chewing food, or waving good-bye when asked to do so.

The two most common forms of apraxia in demented

pa-tients are ideational and gait apraxia. Ideational apraxia is the inability

to perform motor activities that require sequential steps and results from a

lesion involving both frontal lobes or the com-plete cerebrum. Gait apraxia,

often seen in such conditions as normal-pressure hydrocephalus, is the

inability to perform vari-ous motions of ambulation. It also results from

conditions that diffusely affect the cerebrum. Impairment of executive function

is the ability to think abstractly, plan, initiate and end complex behavior. On

Mental Status Examination, patients with dementia display problems coping with

new tasks. Such activities as sub-tracting serial sevens may be impaired.

Obviously, aphasia, agnosia, apraxia and impairment

of executive function can seriously impede the ability of the de-mented

patients to interact with their environment. An appro-priate mental status

examination of the patient with suspected dementia should include screening for

the presence of these abnormalities.

Associated Features and Behavior

In addition to the diagnostic features already

mentioned, patients with dementia display other identifying features that often

prove problematic. Poor insight and poor judgment are common in dementia and

often cause patients to engage in potentially dan-gerous activities or make

unrealistic and grandiose plans for the future. Visual–spatial functioning may

be impaired, and if pa-tients have the ability to construct a plan and carry it

out, suicide attempts can occur. More common is unintentional self-harm

re-sulting from carelessness, undue familiarity with strangers, and disregard

for the accepted rules of conduct.

Emotional lability, as seen in pseudobulbar palsy

after cer-ebral injury, can be particularly frustrating for caregivers, as are

occasional psychotic features such as delusions and hallucina-tions. Changes in

their environment and daily routine can be par-ticularly distressing for

demented patients, and their frustration can be manifested by violent behavior.

Course

The course of a particular dementia is influenced

by its etiology. Although historically the dementias have been considered

pro-gressive and irreversible, there is, in fact, significant variation in the

course of individual dementias. The disorder can be pro-gressive, static, or

remitting (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). In addition to the

etiology, factors that influence the course of the dementia include: 1) the

time span between the onset and the initiation of prescribed treatment, 2) the

degree of reversibil-ity of the particular dementia, 3) the presence of

comorbid psy-chiatric disorders, and 4) the level of psychosocial support. The

previous distinction between treatable and untreatable dementias has been

replaced by the concepts of reversible, irreversible and arrestable dementias.

Most reversible cases of dementia are as-sociated with shorter duration of

symptoms, mild cognitive im-pairment and superimposed delirium. Specifically,

the dementias caused by drugs, depression and metabolic disorders are most

likely to be reversible. Other conditions such as normal pressure

hydrocephalous, subdural hematomas and tertiary syphilis are more commonly

arrestable.

Although potentially reversible dementias should be

ag-gressively investigated, in reality, only 8% of dementias are par-tially

reversible and about 3% fully reversible (Kaufman, 1990b). There is some

evidence to suggest that early treatment of de-mented patients, particularly

those with Alzheimer’s type, with such agents as donepezil, which acts as an

inhibitor of acetylcho-linesterase, and galanthamine may slow the rate of

progression of the dementia.

Differential Diagnosis

Memory impairment occurs in a variety of conditions

includ-ing delirium, amnestic disorders and depression (American Psychiatric

Association, 1994). In delirium, the onset of altered memory is acute and the

pattern typically fluctuates (waxing and waning) with increased proclivity for

confusion during the night. Delirium is more likely to feature autonomic

hyperactivity and alterations in level of consciousness. In some cases a

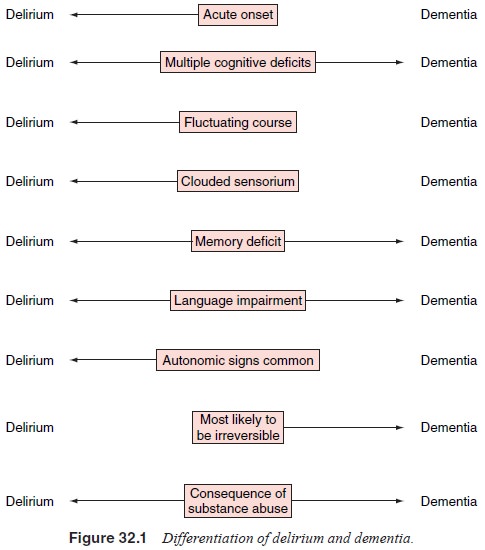

dementia can have a superimposed delirium (Figure 32.1

Patients with major depressive disorder often

complain of lapses in memory and judgment, poor concentration and seem-ingly

diminished intellectual capacity. Often these symptoms are mistakenly diagnosed

as dementia, especially in elderly patients. A thorough medical history and

mental status examination focus-ing on such symptoms as hopelessness, crying

episodes and un-realistic guilt, in conjunction with a family history of

depression, can be diagnostically beneficial. The term pseudodementia has been used to denote cognitive impairment

secondary to a func-tional psychiatric disorder, most commonly depression

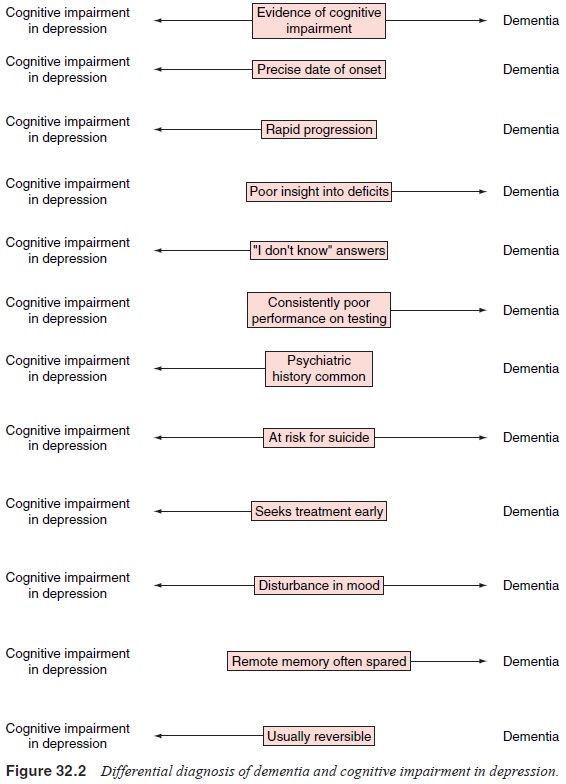

(Korvath et al., 1989). In comparison

with demented patients, those with depressive

pseudodementia exhibit better insight regarding their cognitive dysfunction,

are more likely to give “I don’t know” answers, and may exhibit neurovegetative

signs of depression. Pharmacological treatment of the depression should improve

the cognitive dysfunction as well. Because of the rapid onset of their

antidepressant action, the use of psychostimulants (methylpheni-date,

dextroamphetamine) to differentiate between dementia and pseudodementia has

been advocated by some authors (Frierson et

al., 1991). Some authors have proposed abandonment of the term pseudodementia, suggesting that

most patients so diag-nosed have both genuine dementia and a superimposed

affective disorder (Figure 32.2).

An amnestic disorder also presents with a

significant memory deficit, but without the other associated features such as

aphasia, agnosia and apraxia. If cognitive impairment occurs only in the

context of drug use, substance intoxication or sub-stance withdrawal is the

appropriate diagnosis. Although mental of age and abnormalities of memory do

not always occur. Mental retardation must be considered in the differential

diagnosis of dementias of childhood and adolescence along with such dis-orders

as Wilson’s disease (hepatolenticular degeneration), lead intoxication,

subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, HIV spectrum disorders and substance

abuse, particularly abuse of inhalants. If an individual develops dementia

before age 18 years and has an IQ in the mentally retarded range (i.e., below

70), an additional diagnosis of mental retardation may be justified.

Patients with schizophrenia may also exhibit a

variety of cognitive abnormalities, but this condition also has an early onset,

a distinctive constellation of other symptoms (e.g., delu-sions,

hallucinations, disorganized speech), and does not result from a medical

condition or the persisting effects of a substance. Factitious disorder and

malingering must be distinguished from dementia. The patient with factitious

disorder and psychological symptoms may have some apparent cognitive deficits

reminis-cent of a dementia.

Dementia must also be distinguished from

age-related cognitive decline (also known as benign senescence). Only when such

changes exceed the level of altered function to be expected for the patient’s

age is the diagnosis of dementia warranted (American Psychiatric Association,

1994).

Physical and Neurological Examinations in Dementia

The physical examination may offer clues to the etiology of the dementia; however, in the elderly, one must be aware of the normal changes associated with aging and differentiate them from signs of dementia. Often the specific physical examination findings indicate the area of the central nervous system affected by the etiological process. Parietal lobe dysfunction is suggested by such symptoms as astereognosis, constructional apraxia, ano-sognosia and problems with two-point discrimination (Kaufman, 1990a). The dominant hemisphere parietal lobe is also involved in Gerstmann’s syndrome, which includes agraphia, acalculia, finger agnosia and right–left confusion.

Reflex changes such as hyperactive deep tendon

reflexes, Babinski’s reflex and hyperactive jaw jerk are indicative of cerebral

injury. However, primitive reflexes such as the palmar–mental re-flex (tested

by repeatedly scratching the base of the patient’s thumb, with a positive

response being slight downward movement of the lower lip and jaw), which occurs

in 60% of normal elderly people, and the snout reflex, seen in a third of

elderly patients, are not diag-nostically reliable for dementia (Wolfson and

Katzman, 1983).

Ocular findings such as nystagmus (as in brain stem

lesions), ophthalmoplegia (Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome), anisocoria papilledema

(hypertensive encephalopathy), cortical blindness (Anton’s syndrome), visual

field losses (CVA hemianopia), Kayser–Fleischer rings (Wilson’s disease) and

Argyll Robertson pupils (syphilis, diabetic neuropathy) can offer valuable

clues to the etiology of the cognitive deficit (Victor and Adams, 1974).

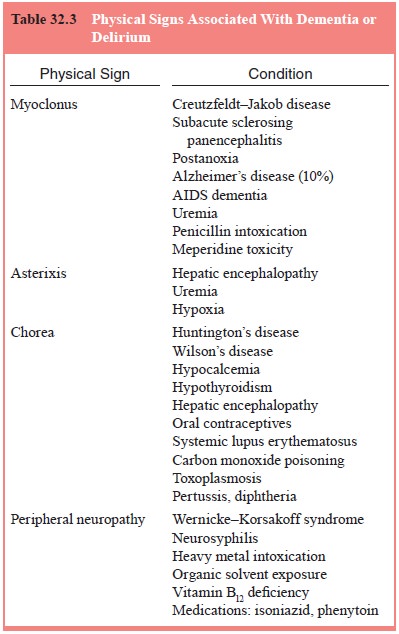

Movement disorders including tremors (Parkinson’s

dis-ease, drug intoxication, cerebellar dysfunction, Wilson’s disease), chorea

(Huntington’s disease, other basal ganglia lesions), myo-clonus (subacute

sclerosing panencephalitis, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, Alzheimer’s disease,

anoxia) and asterixis (hepatic disease, uremia, hypoxia, carbon dioxide

retention) should be noted.

Gait disturbances, principally apraxia

(normal-pressure hydrocephalus, inhalant abuse, cerebellar dysfunction) and

pe-ripheral neuropathy (Korsakoff’s syndrome, neurosyphilis, heavy metal

intoxication, solvent abuse, isoniazid or phenytoin toxicity, vitamin

deficiencies and HIV spectrum illnesses), are

also common in dementia. Extrapyramidal symptoms in

the ab-sence of antipsychotics may indicate substance abuse, especially

phencyclidine abuse, or basal ganglia disease. Although the many and varied

physical findings of dementia are too numer-ous to mention here in any detail,

it should be obvious that the physical examination is an invaluable tool in the

assessment of dementia (Table 32.3).

Mental Status Examination

The findings on the Mental Status Examination vary

depending on the etiology of the dementia. Some common abnormalities have been

discussed previously (see earlier section on clinical features). In general,

symptoms seen on the Mental Status Ex-amination, whatever the etiology, are

related to the location and extent of brain injury, individual adaptation to

the dysfunction, premorbid coping skills and psychopathology, and concurrent

medical illness.

Disturbance of memory, especially primary and

second-ary memory, is the most significant abnormality. Confabulation may be

present as the patient attempts to minimize the memory impairment.

Disorientation and altered levels of consciousness may occur, but are generally

not seen in the early stages of de-mentia uncomplicated by delirium. Affect may

be affected as in the masked facies of Parkinson’s disease and the expansive

affect

and labile mood of pseudobulbar palsy after

cerebral injury. The affect of patients with hepatic encephalopathy is often

described as blunted and apathetic. Lack of inhibition leading to such behavior

as exposing oneself is common, and some conditions such as tertiary syphilis

and untoward effects of some medication can precipitate mania. The Mental Status

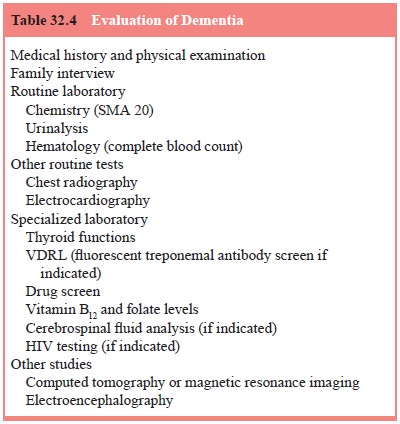

Examination, in conjunction with a complete medical history from the patient

and informants and an adequate physical examination, is essential in the

evaluation and differential diagnosis of dementia (Table 32.4).

Related Topics