Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Delirium and Dementia

Amnestic Disorders

Amnestic Disorders

The amnestic disorders are characterized by a

disturbance in memory related to the direct effects of a general medical

condi-tion or the persisting effects of a substance (American Psychiatric

Association, 1994). The impairment should interfere with social and

occupational functioning and represent a significant decline from the previous

level of functioning. The amnestic disorders are differentiated on the basis of

the etiology of the memory loss. These disorders should not be diagnosed if the

memory deficit is a feature of a dissociative disorder, is associated with

demen-tia, or occurs in the presence of clouded sensorium, as in delir-ium.

Amnestic disorders are predominately comprised of those caused by a general

medical condition or those whose etiology is substance-induced.

Epidemiology

The exact prevalence and incidence of the amnestic

disorders are unknown (Kaplan et al.,

1994). Memory disturbances related to specific conditions such as alcohol

dependence and head trauma have been studied and these appear to be the two

most common causes of amnestic disorders. Kaplan and coworkers (Torres et al., 2001) reported that in the

hospital setting the incidence of alcohol-induced

amnestic disorders is decreasing while that of amnestic disorders, secondary to

head trauma, is on the rise. This may be related to rigorous efforts by

hospital personnel to decrease the incidence of iatrogenic amnestic disorder by

giving thiamine before glucose is administered to a patient with chronic

alcohol dependence and nutritional deficiencies.

Etiology

Amnesia results from generally bilateral damage to

the areas of the brain involved in memory. The areas and structures so

in-volved include the dorsomedial and midline thalamic nuclei, such temporal

lobe-associated structures as the hippocampus, amy-gdala and mamillary bodies.

The left hemisphere may be more important than the right in the occurrence of

memory disorders. Frontal lobe involvement may be responsible for such commonly

seen symptoms as apathy and confabulation.

The specific causes of amnestic disorders include

1) sys-temic medical conditions such as thiamine deficiency; 2) brain

conditions, including seizures, cerebral neoplasms, head injury, hypoxia,

carbon monoxide poisoning, surgical ablation of tem-poral lobes,

electroconvulsive therapy and multiple sclerosis; 3) altered blood flow in the

vertebral vascular system, as in tran-sient global amnesia; and 4) effects of a

substance (drug or alco-hol use and exposure to toxins).

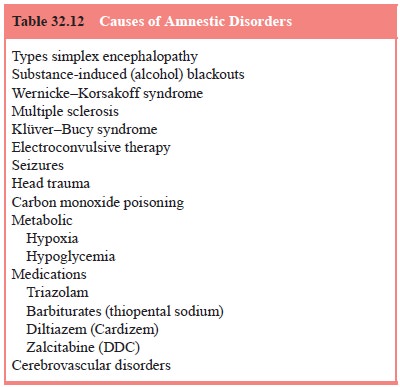

Conditions that affect the temporal lobes such as

herpes infection and Kluver–Bucy syndrome can produce amnesia. Among drugs that

can cause amnestic disorders, triazolam has received the most attention, but

all benzodiazepines can produce

memory impairment, with the dose utilized being the

determin-ing factor (Kirk et al.,

1990) (Table 32.12).

Clinical Features

Patients with amnestic disorder have impaired

ability to learn new information (anterograde amnesia) or cannot remember

ma-terial previously learned (retrograde amnesia). Memory for the event that

produced the deficit (e.g., a head injury in a motor ve-hicle accident) may

also be impaired.

Remote recall (tertiary memory) is generally good, so pa-tients may be able to relate accurately incidents that occurred during childhood but not remember what they had for breakfast. As illus-trated by such conditions as thiamine amnestic syndrome, immedi-ate memory is often preserved. In some instances, disorientation to time and place may occur, but disorientation to person is unusual.

The onset of the amnesia is determined by the

precipitant and may be acute as in head injury or insidious as in poor

nu-tritional states. DSM-IV characterizes short-duration amnestic disorder as

lasting less than 1 month and long-duration disorder lasting 1 month or longer.

Often individuals lack insight into the memory deficit and vehemently insist

that their inaccurate re-sponses on a Mental Status Examination are correct.

Selected Amnestic Disorders

Blackouts

Blackouts are periods of amnesia for events that

occur during heavy drinking (Tarter and Schneider, 1976). Typically, a person

awakens the morning after consumption and does not remember what happened the

night before. Unlike delirium tremens, which is related to chronicity of

alcohol abuse, blackouts are more a measure of the amount of alcohol consumed

at any one time. Thus, blackouts are common in binge pattern drinkers and may

occur the first time a person ingests a large amount of alcohol. Blackouts are

generally transient phenomena, but some patients may continue to have blackouts

for weeks even after they have stopped using alcohol. These memory lapses are

similar to black-outs experienced while using alcohol. With continued sobriety,

the blackouts should end, but information forgotten during past blackouts is

never remembered. Blackouts may also be produced by agents with

cross-sensitivity to alcohol, such as benzodi-azepines. Blackouts should not be

confused with alcohol-induced dementia, which presents with cortical atrophy on

CT scans, as-sociated features of dementia and a usually irreversible course.

Korsakoff’s Syndrome

Korsakoff’s syndrome is an amnestic disorder caused

by thia-mine deficiency. Although generally associated with alcohol abuse, it

can occur in other malnourished states such as maras-mus, gastric carcinoma and

HIV spectrum disease (Reulen et al.,

1985; Victor, 1987). This syndrome is usually associated with Wernicke’s

encephalopathy, which involves ophthalmoplegia, ataxia and confusion.

Korsakoff’s syndrome is often associated with a neuropathy and occurs in about

85% of untreated patients with Wernicke’s disease (Kaplan et al., 1994). Complete recovery from Korsakoff’s syndrome is rare.

Head Injury

Head injuries can produce a wide variety of

neurological and psy-chiatric disorders, even in the absence of radiological

evidence of structural damage. Delirium, dementia, mood disturbances,

behavioral disinhibition, alterations of personality and amnestic disorders may

result (Torres et al., 2001). Amnesia

in head injury is for events preceding the incident and the incident itself,

lead-ing some physicians to consider these patients as having facti-tious

disorders or being malingerers. The eventual duration of the amnesia is related

to the degree of memory recovery that occurs in the first few days after the

injury. Amnesia after head injury has become a popular plot device in novels

and motion pictures, many of which are depictions that erroneously suggest that

a sec-ond blow to the head is curative

Differential Diagnosis

Amnestic disorders must be differentiated from the

less disrup-tive changes in memory that occur in normal aging, the memory

impairment that is accompanied by other cognitive deficits in dementia, the

amnesia that might occur with clouded conscious-ness in delirium, the

stress-induced impairment in recall seen in dissociative disorders, and the

inconsistent amnestic deficits seen in factitious disorder and malingering.

Treatment

As in delirium and dementia, the primary goal in

the amnestic dis-orders is to discover and treat the underlying cause. Because

some of these causes of amnestic disorder are associated with dangerous

self-damaging behavior (e.g., suicide attempts by hanging, carbon monoxide

poisoning, deliberate motor vehicle accidents, self-in-flicted gunshot wounds

to the head and chronic alcohol abuse), some form of psychiatric involvement is

often necessary. In the hospital, continuous reorientation by means of verbal

redirection, clocks and calendars can allay the patient’s fears. Supportive

indi-vidual psychotherapy and family counseling are beneficial.

Related Topics