Chapter: Modern Medical Toxicology: Substance Abuse: Substances of Dependence and Abuse

Cocaine: Diagnosis, Treatment - Substances of Dependence and Abuse

Diagnosis

·

Blood or plasma cocaine levels are not clinically useful,

although they may be advisable to be done in medico-legal cases. Qualitative

urine tests using kits may be helpful in clinical diagnosis (by utilising

chromatography, radioim-munoassay, enzyme immunoassay, fluorescence

polarisa-tion immunoassay, and enzyme-multiplied immunoassay technique).

Cocaine metabolites can be identified in the urine and provide a method for

qualitatively identifying suspected cocaine poisoning or abuse.

Benzoylecgonine, the major metabolite of cocaine, can usually be detected in

urine for 48 to 72 hours after cocaine use.

·

Other diagnostic clues—

o Hair analysis: Cocaine benzoylecgonine and ecgo-nine methylester can be

analysed in hair samples by GC-MS and RIA. This can be done in adults, as well

as in any infant whose mother was a cocaine user. It must be noted that

external contamination of hair can occur from crack smoke, but that can be

washed off, whereas systemic exposure is not affected by washing the hair.![]()

o ECG: Non-Q-wave myocardial infarction, with the pres-ence of a

T-wave infarct ECG pattern is often seen in cocaine users. During acute cocaine

use abnormalities are more prevalent, and the QT interval is prolonged.

Two-dimensional echocardiography may be useful in detecting the presence of new

regional wall-motion abnormalities in patients experiencing cocaine-induced

chest pain.

o Troponin levels may be more useful

in evaluating potential myocardial injury than creatinine kinase.

o Acid-base abnormalities: Arterial blood gases incocaine

abusers show a pH varying from 7.35 to 7.5. Alkalosis (pH > 7.45) is caused

by hyperventilation, and is manifested by tachypnoea and low PaCO2.

About one third of patients show evidence of acidosis which may be the result

of hypoventilation secondary to depressed mental status or chest trauma.

Metabolic acidosis is not uncommon, and usually results from convulsions,

agitation, or trauma.

o Estimate serum creatine kinase for

evidence of rhab-domyolysis. Monitor renal function and urine output in

patients with elevated CPK.

o X-ray: Body packer syndrome can bediagnosed by plain films of the

abdomen in the supine and upright positions. However, false negatives have been

reported. Radiography may not detect cellophane-wrapped packets or crack vials.

Even false-negative abdominal CT scans have been reported. It is therefore

advisable to perform a contrast study of the bowel with follow-up X-rays 5

hours after the oral ingestion of a water-soluble contrast compound such as

meglumine amidotrizoate (50 ml). Daily views are performed there-after until

negative views coincide with the passage of two drug packet-free stools.

Treatment

Acute Poisoning

Activated

charcoal adsorbs cocaine in vitro under both acidic and alkaline conditions,

and can be administered in cases of ingestion.

a. Hyperthermia:

––

Minimise physical activity and sedate with benzo-diazepines.

––

Ice baths, packs, cool water with fans, etc. –– Oxygen D50W

(as necessary).

––

Diazepam 5 mg IV or lorazepam 2–4 mg IV titrated to effect.

––

Paracetamol 2000 mg (in the form of 500 mg rectal suppositories).

–– Severe, intractable cases may respond to dantrolene (1 mg/kg) every 6 hours. Alternatively, bromocrip-tine can be administered orally in a nasogastric tube.

b. Anxiety and agitation:

––

Diazepam 5–10 mg IV, or lorazepam 2–4 mg IV titrated to effect.

–– Physical restraints.

––

Antipsychotics such as haloperidol or droperidol, and phenothiazines are not

recommended since they can induce malignant hyperthermia and convul-sions.

c.

Convulsions:

––

Diazepam 5–10 mg IV, or lorazepam 2–4 mg IV titrated to effect.

–– Phenobarbitone 25–50 mg/min up to 10–20

mg/kg. –– If seizures are not controlled

by the above measures, consider continuous infusion of midazolam (0.2 mg/ kg

slow bolus, or 0.75 to 10 mcg/kg/min as infu-sion), or propofol (1 to 2 mg/kg,

followed by 2 to 10 mg/kg/hr) or pentobarbitone (10 to 15 mg/kg at a rate of 50

mg/min, followed by 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/hr).

––

Intractable convulsions may require neuromuscular paralysis with intubation and

mechanical

ventila-tion.

d. Cerebrovascular accidents:

Neurosurgical consultation is mandatory.

e. Hypertension: It is usually

short-lived and often followed by significant hypotension. Mild hypertension

generally responds to sedation with benzodiazepines. For severe hypertension—

––

Without tachycardia:

-- Phentolamine 0.02 to 0.1 mg/kg IV

-- Nifedipine 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg IV

--

Nitroprusside 2 to 10 mcg/kg/min IV

–– With tachycardia: If the above

measures are not effective, the following may be used—

-- Labetolol 10 to 20 mg IV,

repeated every 10 minutes (max: 300 mg).

-- Nitroglycerine IV titrated to

effect. –– With chest pain—

--

Nitroglycerine drip.

-- Oxygen by nasal cannula (5

L/min). -- Monitor cardiac status.

-- If systolic BP is higher than 120

mmHg, admin-ister nitroglycerine sublingually (up to 3 tablets or 3 sprays of

0.4 mg each).

-- If pain does not respond to

nitroglycerine, use morphine (2 mg IV titrated to pain relief).

--

Obtain ECG.

--

If chest pain is strongly suggestive of a myocar-dial infarction,

consider thrombolytic therapy.

-- Diazepam 5 mg IV, or lorazepam

2–4 mg IV titrated to effect can prevent excess production of catecholamines by

the CNS.

--

Mechanical reperfusion (angioplasty).

f. Arrhythmias:

–– Sinus tachycardia: -- Observation

-- Oxygen

--

D50W (as necessary)

--Diazepam 5–10 mg IV, or lorazepam

2–4 mg IV titrated to effect (if indicated).

–– Supraventricular tachycardia: --

Observation

--

Oxygen

--

D50W ( as neccesary)

-- Diltiazem 20 mg IV, or verapamil

5 mg IV -- Adenosine 6–12 mg IV for AV node re-entry -- Cardioversion (if

necessary).

–– Ventricular arrhythmias: Obtain

an ECG, institute continuous cardiac monitoring and administer oxygen. Evaluate

for hypoxia, acidosis, and electrolyte disorders (particularly hypokalaemia,

hypocalcaemia, and hypomagnesaemia).

--

Oxygen

--

D50W (as necessary)

-- Hypertonic sodium bicarbonate:

Sodium bicarbonate may be useful in the treatment of QRS widening and

ventricular arrhythmias associated with acute cocaine use. A reason-able

starting dose is 1 to 2 mEq/kg repeated as needed. Monitor arterial blood

gases, maintain pH 7.45 to 7.55.

-- Diazepam 5 mg IV, or lorazepam

2–4 mg IV. -- Lignocaine 1.5 mg/kg IV bolus, followed by 2 mg/min infusion.

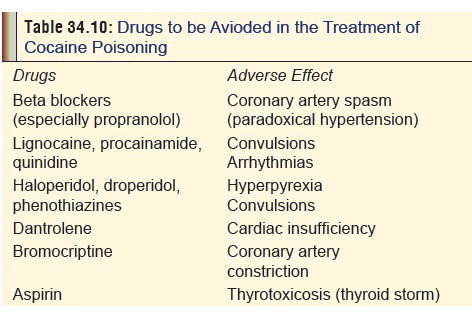

Watch out for adverse effects (Table

34.10). Procainamide may also be used with caution.

--

Defibrillation (if haemodynamically unstable).

g. Myocardial infarction: Acute

myocardial infarction due to cocaine toxicity must be treated on the same lines

as myocardial infarction in non-cocaine users, except for the use of beta

blockers. The following measures are recommended:

–– IV line –– Oxygen

–– Aspirin to inhibit platelet

aggregation. Watch out for increased thyroxine levels.

–– For systolic BP higher than 100

mmHg, administer sublingual nitroglycerine or nifedipine 10 mg orally, or

phentolamine 1 to 5 mg IV (followed by a drip of 10 mg in 1 litre of D5W

at 10 ml/min).

--For life-threatening arrhythmias,

use of type IA antiarrhythmic agents may be considered (with caution).

--Thrombolytic therapy may be

necessary if myocardial infarction is not amenable to relief by nitrates,

calcium channel blockers, or phentolamine. Caution about the use of

throm-bolytics in cocaine-associated acute myocar-dial infarction (AMI) is

generally advocated. Thrombolytics should be avoided in patients with

cocaine-induced myocardial infarction and uncontrolled hypertension, because of

the increased risk of intracranial haemorrhage. However, some investigators

feel that the risk is often exaggerated.

h. Aortic dissection: The

hypertension that precipitated aortic dissection must be controlled immediately

with nitroprusside and calcium channel blockers.

i. Pulmonary oedema:

––

Frusemide 20–40 mg IV.

–– Morphine sulfate 2 mg IV titrated

to pain relief. –– Nitroglycerine drip titrated to blood pressure or

respiratory status.

–– Phentolamine or nitroprusside (if

necessary). –– Incubate and ventilate.

––

Monitor fluids with pulmonary artery catheter.

j. Rhabdomyolysis: Early aggressive

fluid replacement is the mainstay of therapy and may help prevent renal

insufficiency. Diuretics such as mannitol or furosemide may be needed to

maintain urine output. Urinary alka-linisation is not routinely recommended.

––

Cardiac monitoring.

––

Serial potassium determinations.

–– Serial serum creatine kinase and

urine myoglobin studies.

–– IV hydration (urine output must

be maintained at 3 ml/kg/hr).

–– Dopamine (3 mcg/kg/day) and

frusemide (60 mg three times a day) may reduce renal vascular resist-ance and

help in reducing the number of haemodi-alysis required to reverse oliguria.

k. Acidosis: Correction of acidaemia

through supportive care measures such as hyperventilation, sedation, active

cooling, and sodium bicarbonate infusion can have beneficial effects on

conduction defects.

l. Elimination enhancement measures:

Cocaine is rapidly metabolised. Forced diuresis, urine acidifica-tion,

dialysis, and haemoperfusion are ineffective in significantly altering

elimination. Increasing the level of butyrylcholinesterase in the blood (which

metabolises cocaine to inactive compounds) could help in rapidly inactivating

cocaine in acute intoxications.

Chronic Poisoning

A number of psychological and

pharmacological approaches to the treatment of cocaine dependence have been

tried with varying degrees of success. A combined approach judiciously tailored

to the needs of individual patients offers the best hope of preventing

relapses.![]()

a. Psychotherapy: This involves

cognitive-behavioural, psychodynamic, and general supportive techniques.

One example of a

cognitive-behavioural method uses contingency contracting, in which it is

agreed in advance that for a specified period of time (e.g. 3 months), if the

patient uses cocaine (as detected by supervised urine testing), the therapist

will initiate action that will result in serious adverse consequences for the

patient, such as informing the employer.

b. Group psychotherapy:

–– Interpersonal group therapy

focuses on relation-ships, and uses the group interactions to illustrate the

interpersonal causes of individual distress, and to offer alternative

behaviours.

–– Modified dynamic group therapy is

concerned with emphasising character as it manifests itself indi-vidually and

intrapsychically, and in the context of interpersonal relationships with a

focus on affect, self-esteem and self-care.

c. Group counselling: The most

widely used form of psychosocial treatment for cocaine dependence is group

counselling, in which the group is open-ended with rolling admissions; the

group leaders are drug counsellors, many of whom are recovering from addiction,

and the emphasis is on providing a supportive atmosphere, discussing problems

in recovery, and encouraging participation in multistep programmes.

d. Pharmacotherapy:

–– Several drugs have been tried to

help ameliorate the manifestations of cocaine withdrawal. Many of these

(fenfluramine, trazodone, neuroleptic agents, etc.) have either not

demonstrated clinical efficacy, or have produced serious side effects.

––

Bromocriptine has successfully reduced cocaine craving and decreased

withdrawal symptoms in several studies. Oral doses of 0.625 mg given 4 times

daily may produce a rapid decrease in psychiatric symptoms. When given in a

single dose of 1.25 mg, bromocriptine has been found to decrease cocaine

craving. In one study, the dosage suggested was 1.25 mg orally twice daily,

with titration up to 10 mg per day within the first 7 days.

Dose can be decreased in patients

experiencing adverse effects.

–– Amantadine, a dopamimetic agent, increases dopaminergic transmission and has been found to be useful in the treatment of early withdrawal symptoms and short-term abstinence. The usual dose recommended is 200 mg to 400 mg orally, daily, for up to 12 days. It is probably as effective as bromocriptine, and less toxic.

–– Tricyclic antidepressants may be useful for selected cocaine users with comorbid depression or intra-nasal use.

–– Initial studies with fluoxetine promised good results, but craving actually worsened in some patients. Several studies indicated better effi-cacy with carbamazepine for controlling craving. Carbamazepine at doses of 200 to 800 mg orally, 2 to 4 times daily has benefited some patients. Phenytoin also shows promise in helping to sustain abstinence from cocaine in some patients.

–– Recent approaches include the

employment of agents that selectively block or stimulate dopa-mine receptor

subtypes (e.g. selective D1 agonists), and drugs that can

selectively block the access of cocaine to the dopamine transporters, and yet

still permit the transporters to remove cocaine from the synapse.

–– Another approach is aimed at

preventing cocaine from reaching the brain by using antibodies to bind cocaine

in the blood stream (“cocaine vaccine”).

e. Acupuncture: Use of auricular

acupuncture to treat cocaine abuse has become popular of late, though

controlled studies of its efficacy have not shown convincing results. Herbal

teas are often consumed as part of the treatment. Unfortunately, drop-out rates

are generally high.

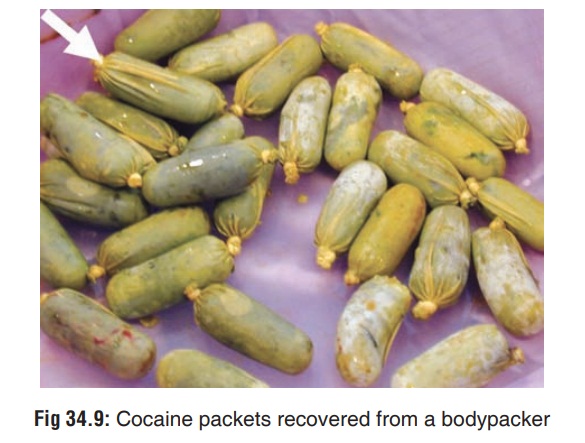

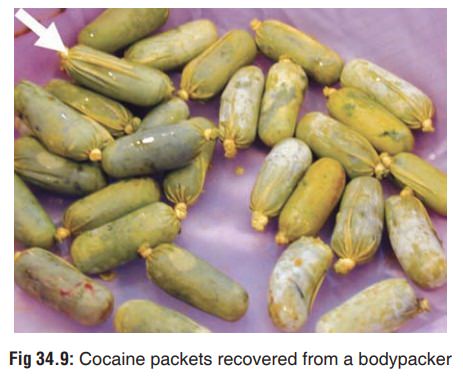

Bodypacker Syndrome

The practice of swallowing balloons,

condoms, or plastic packets filled with illegal drugs for the purpose of

smuggling is called “body packing”, (Fig

34.9) and the individual who does this is referred to as a “mule”. This

must be differentiated from “body stuffing” in which an individual who is on

the verge of being arrested for possession of illegal drugs, swallows his illicit

contraband to conceal the evidence. Leaking from these poorly wrapped packets

can produce cocaine toxicity. Sudden death due to massive overdose can occur in

either a bodypacker or a bodystuffer, if one or more of the ingested packages

burst within the gastrointestinal tract. Fatal cocaine poisoning has occurred

with the rupture of just a single package.

a. Diagnosis

b. Treatment:

–– Emesis, lavage, charcoal, as applicable.

–– Cathartic/whole bowel irrigation

to flush the pack-ages out of the intestines.

–– Symptomatic patients should be

considered a medical emergency, and be evaluated for surgical removal of the

packets.

–– Asymptomatic patients should be

monitored in an intensive care unit until the cocaine packs have been

eliminated. This must be confirmed by follow-up plain radiography and barium

swallows.

–– Bowel obstruction in asymptomatic

patients may necessitate surgery. Endoscopic removal has been successful in

some cases.

Autopsy Features

·

There are no specific findings at autopsy, except for nasal

septal ulceration and perforation if the deceased had been a long-term abuser

of cocaine. Histological study of nasal septal mucosa in such cases may reveal

characteristic changes including arteriolar thickening, increased perivas-cular

deposition of collagen and glycoprotein, and chronic inflammatory cellular

infiltration.

·

Histopathology of heart may demonstrate microfocal

lymphocytic infiltrates, acute coronary thrombosis, early coagulation necrosis

of myocardial fibres, and non-athero-sclerotic coronary obstruction due to

intimal proliferation.

·

Cocaine can be recovered by sampling from recent injec-tion

sites, or by swabs from the nasal mucosa. It can also be recovered from the

liver and especially brain, where cocaine may be found not only in

dopamine-rich areas such as caudate, putamen, and nucleus accumbens, but also

in other extra-striatal regions. Specimens obtained postmortem should be

preserved with sodium fluoride, refrigerated, and analysed quickly. Tissue

specimens should be frozen.

Forensic Issues

·

Cocaine has been abused for centuries, but its toxic proper-

ties have been studied extensively only in the last couple of decades. In the current drug subculture,

cocaine has become the “champagne drug”

because of its cost and relative scarcity. Cocaine is a “rich man’s drug” since

the poorer classes cannot afford to sustain a drug habit that costs thousands

of rupees every week. Therefore in India, cocaine abuse is restricted mainly to

the affluent classes of society. The prevalence and extent of the problem among

newer generation Indian film actors in recent times has become apparent with

the arrest of several filmstars for possession of cocaine. Several high profile

artists, socialites, and even politicians have been caught with cocaine

possession.

·

Cocaine has always been popular with musicians (espe- cially

jazz and rock), other artistes, and film personalities. There are innumerable

rock songs eulogising the drug directly or indirectly.

·

Today cocaine has made inroads into the general popula-tion,

especially adolescents. After the cocaine epidemic of the 1970s (“snorting

seventies”) in the West, there had been relative lull in the 1980s and early

1990s. A recent survey shows the cocaine resurgence of the 21st century has not

only affected Western countries, but even poorer countries such as India. In

fact a sizeable chunk of youth (including girls) from well-to-do families in

metropolitan cities such as

·

Mumbai, Delhi, and Bangalore have no qualms about drug

abuse, and even openly admit to using “party drugs” such as cocaine as a “cool”

mode of recreation. Since cocaine has a reputation of enhancing sexual

pleasure, such wide-spread abuse has also led to increased spread of sexually

transmitted diseases such as AIDS because of high-risk sexual practices among

the users.

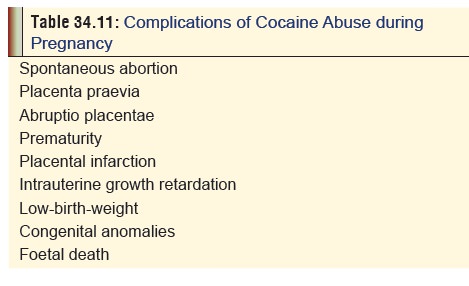

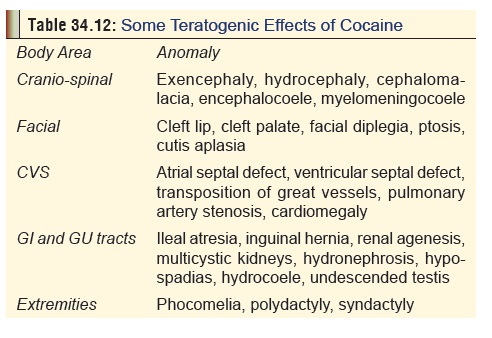

·

Cocaine abuse by pregnant mothers can lead to devastating

effects on the foetus and the new-born (Table

34.11). There is convincing evidence that cocaine is teratogenic and can

play an important role in the causation of several serious congenital anomalies

(Table 34.12).

·

Cocaine abuse is well known for its propensity to cause

sudden death not only due to its deleterious effects onhealth (cerebrovascular

accidents, myocardial infarction, malignant hyperthermia, renal failure), but

also due to its capacity to provoke the user to commit acts of aggression and

violence. Deaths due to massive overdose are especially common among those who

smuggle the drug within their bodies (“cocaine packers”).

· Cocaine toxicity has been reported in children receiving topical adrenaline and cocaine for local anaesthesia.

Related Topics