Chapter: Pharmaceutical Drug Analysis: Errors In Pharmaceutical Analysis and Statistical Validation

Classification of Errors in Pharmaceutical Analysis

CLASSIFICATION OF ERRORS

The numerous uncertainties usually encountered in a

chemical analysis give rise to a host of ‘errors’ that may be broadly categorised

into two heads, namely :

(i) Determinate

(systematic) Errors, and

(ii)

Indeterminate (random) Errors.

It is pertinent to mention here that it becomes rather

difficult at times to place a particular ‘error’ into one of the above

mentioned categories ; however, the classification may prove to be beneficial

with regard to study of the various analytical errors that crop up in the

course of routine analysis.

1. DETERMINATE (SYSTEMATIC) ERRORS

These are errors that possess a definite value together

with a reasonable assignable cause; however, in principle these avoidable

errors may be measured and accounted for coveniently. The most important errors

belonging to this particular class are :

(a) Personal Errors : They are exclusively

caused due to ‘personal equation’ of an analyst and have no bearing whatsoever

either on the prescribed procedure or methodology involved.

(b) Instrumental Errors : These are

invariably caused due to faulty and uncalibrated instruments, such as : pH

meters, single pan electric balances, uv-spectrophotometers, potentiometers

etc.

(c) Reagent Errors : The errors that are

solely introduced by virtue of the individual reagents, for instance :

impurities inherently present in reagents ; high temperature volatalization of

platinum (Pt) ; unwanted introduction of ‘foreign substances’ caused by the

action of reagents on either porcelain or glass apparatus.

(d) Constant Errors : They are observed to

be rather independent of the magnitude of the measured amount ; and turn out to

be relatively less significant as the magnitude enhances.

Example : Assuming a constant

equivalence—point error of 0.10 ml is introduced in a series of titrations,

hence for a specific titration needing only 10.0 ml of titrant shall represent

a relative error of 1% and only 0.2% for a corresponding 50 ml of titrant

consumed.

(e) Proportional Errors : The absolute

value of this kind of error changes with the size of the sample in such a

fashion that the relative error remains constant. It is usually incorporated by

a material that directly interferes in an analytical procedure.

Example : Estimation of ‘chlorate’—an

oxidant by iodometric determination. In this particular instance two things may happen, namely :

(i) Presence of

‘Bromate’—another oxidizing agent would give rise to positively higher results,

and hence, it must be duly corrected for, and

(ii) Absolute

error might increase while dealing with large samples, whereas the relative

error would remain more or less constant if the sample is perfectly homogenous,

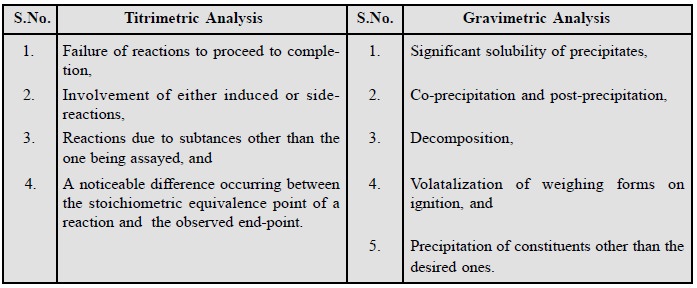

(f) Errors due to Methodology : Both

improper (incorrect) sampling and incompleteness of a reaction often lead to

serious errors. A few typical examples invariably encountered in titrimetric

and gravimetric analysis are cited below :

(g) Additive Errors : It has been observed

that the additive errors are independent of the quantum of the substances

actually present in the assay.

Examples : (i) Errors caused due to weights, and

(ii) Loss in

weight of a crucible in which a precipitate is incenerated.

Detection of this error is ascertained by taking samples

of different weights.

2. INDETERMINATE (RANDOM) ERRORS

As the name suggests, indeterminate errors cannot be

pin-pointed to any specific well-defined reasons. They are usually manifested

due to the minute variations which take place inadvertently in several

successive measurements performed by the same analyst, using utmost care, under

almost identical experimental parameters. These errors are mostly random in

nature and ultimately give rise to high as well as low results with equal

probability. They can neither be corrected nor eliminated, and therefore, form

the ‘ultimate limitation’ on the specific measurements. It has been observed that

by performing repeated measurement of the

same variable, the subsequent statistical treatment of the results would have a

positive impact of ‘reducing their importance’ to a considerable

extent.

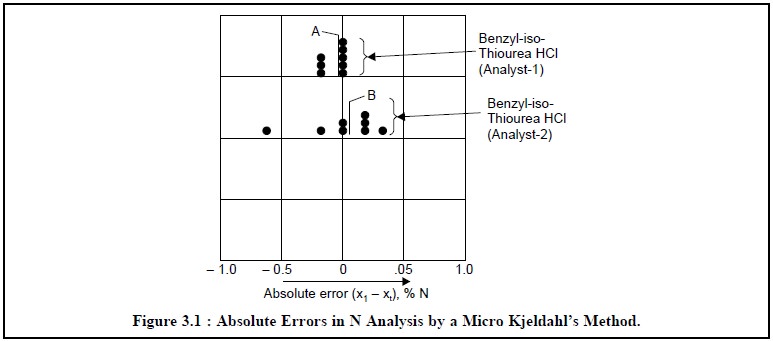

Example : Figure 3.1, represents the

absolute errors in nitrogen analysis by means of micro Kjeldahl’s Method*. Here, each vertical line

labelled ( x’1 – xt)

designates the absolute deviation of the mean of the set from the true value. In Figure 3.1, A represents ( x’1 – xt) the absolute error obtained by ‘analyst-1’ for the assay of benzyl-iso-thioureahydrochloride,

whereas B represents ( x’2

– xt) the absolute error

obtained by ‘analyst-2’ for the

assay of the same compound.

Thus, it is evident from Figure 3.1, that the broad

spread of individual errors centres around the mean values (x’n – x ) thereby affording a direct indication of indeterminate type

uncertainties. Hence, larger indeterminate errors seem to be linked with the

performance of ‘analyst-2’ than with

that of ‘analyst-1’.

![]()

Salient Features of Indeterminate Errors

The various salient features of indeterminate errors are

enumerated below :

1)

Repeated mesurement of the same variable several times

and subsequent refinement to the extent where it is simply a coincidence if the

corresponding replicates eventually agree to the last digit,

2)

Both unpredictable and imperceptible factors are

unavoidably incorporated in the results what generally appear to be ‘random fluctuations’ in the measured

quantity,

3)

Recognition of specific definite variables which are

beyond anyone’s control lying very close to the performance limit of an

instrument, such as : temperature variations, noise as well as drift from an

electronic circuit, and vibrations caused to a building by heavy

vehicular-traffic,

4)

A variation that may be regarded as random by a slipshod

analyst may at the same time prove to be quite evident and manageable by a

careful observer, and

5)

The average of a number of fine observations having

random scatter is definitely more accurate, precise and, hence, more cogent than

coarse data that appear to agree perfectly.

3. ACCURACY

In connexion with the scientific data the two

terminologies ‘accuracy’ and ‘precision’ are invariably practised

synonymously, but there exists a clear distinction between them as discussed

below :

In usual practice an accurate result is the one which

matches very nearly with true value of a measured amount. The comparison is

normally done with regard to the ‘error’;

and the accuracy is inversely propor-tional to it i.e., the greater the accuracy, the smaller is the error. ‘Absolute error’ is the difference

between the experimental value and

the true value.

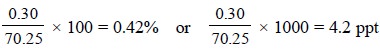

Example : An analyst determines a value

of 70.55% cineole in a fresh sample of Eucalyptus Oil that actually contains

70.25%, the absolute error is given by :

70.55 – 70.25 = 0.30%

The error thus obtained is invariably stated with regard

to the actual size of the measured quantity i.e.,

either in percent (%) or in parts per thousand (ppt). Therefore, the relative

error is given by :

4. PRECISION

It may be defined as—‘the

agreement amongst a cluster of experimental results ; however, it does not imply anything with respect to their

relation to the ‘true value’ ’. Precision designates ‘reproducibility’ of a measurement, whereas accuracy the

correctness of a measurement. Precision invariably forms an integral part of

accuracy, but ironically a high degree of precision may not necessarily suggest

accuracy.

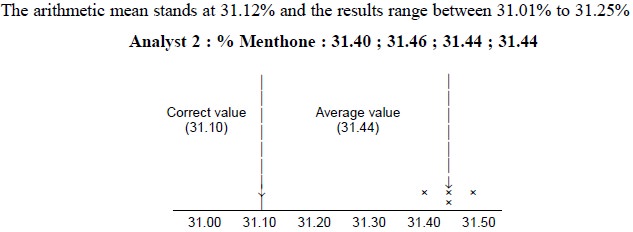

Example : A sample of pure Peppermint

Oil is known to contain 30.10 ± 0.03 per cent of Menthone. The results obtained by

two Analysts-1 and 2 employing the same sample of peppermint oil and making use

of the same analytical reagents and procedure are as stated below :

The arithmetic mean is 31.44% and the results vary

between 31.40% to 31.46%

The ultimate results of the analysis put forward by the

Analysts-1 and 2 may be summarized as under :

(i) The results

achieved by Analyst-1 are fairly accurate i.e.,

in close proximity to the correct result ; however, the precision stands at an

inferior level to the results obtained by Analyst-2. The results accomplished

by Analyst-2 are indeed extremely precise but fail in accuracy,

(ii) The

results of Analyst-1 lie on either sides of the average value as shown by two

‘cross-signs’ on each side which might have been caused due to ‘random errors’

discussed earlier. It is quite evi-dent that there exists a constant

(determinate) error in the results obtained by the Analyst-2, and

(iii) In case,

Analyst-3 had performed the estimations on the very same day in quick

succession i.e., one after the other,

this type of analysis could be termed as ‘repeatable analysis’. If the

estimations had been carried out on two separate days altogether, thereby

facing different laboratory conditions then the results so obtained would be

known as ‘reproducible analysis’.

In short, there exists a marked and pronounced

distinction between a within-run precision (i.e.,

repeatability) and an in-between-run

precision (i.e., reproducibility).

5. MINIMISING SYSTEMATIC ERRORS

Systematic errors may be reduced substantially and

significantly by adopting one of the following procedures rigidly, such as :

(i) Calibration of Instruments, Apparatus and

Applying Necessary Corections

Most of the instruments, commonly used in an analytical

laboratory, such as : UV-Spectrophoto-meter, IR-Spectrophotometer, single—pan

electric balance, pH-meter, turbidimeter and nephelometer, polarimeter,

refractometer and the like must be calibrated duly, before use so as to

eliminate any possible errors. In the same manner all apparatus, namely :

pipettes, burettes, volu-metric flasks, thermometers, weights etc., must be

calibrated duly, and the necessary corrections incorporated to the original

measurements

In some specific instances where an error just cannot be

avoided it may be convenient to enforce an appropriate correction for the

effect that it ultimately causes ; for instance : the inherent impu-rity

present in a weighed precipitate can be estimated first and then deducted duly

from its weight.

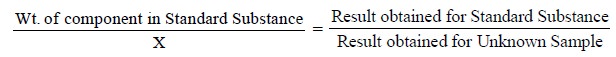

(ii) Performing a Parallel Control Determination

It essentially comprises of performing an altogether

separate estimation under almost identical experimental parameters with a

quantity of a standard substance that consists of exactly the same weight of

the component as is present in the unknown sample. Thus, the weight of the

component present in the unknown sample may be calculated with the help of the

following expression :

where, X = Weight of the component present in the Unknown

Sample.

Note : A good number of

Standard Samples, including primary standards, such as : arsenic trioxide,

benzoic acid, potassium hydrogen phthalate, sodium oxalate, are available as :

BPCRS = British Pharmacopoeia

Chemical Reference Substance,

EPCRS = European Pharmacopoeia

Chemical Reference Substance,

CRM = BCS—Certified Reference

Materials,

ECRM = EURONORM—Certified

Reference Materials.

(iii) Blank Determination :

In order to ascertain the effect of the impurities

present in the reagents employed and reaction vessels used ; besides

establishing exactly the extent to which an excess of standard solution

required to locate the exact end-point under the prevailing experimental

parameters of the unknown sample—a blank determination is an absolute

necessity. It may be accomplished by performing a separate parallel estimation,

without using the sample at all, and under identical experimental parmeters as

employed in the actual analysis of the given sample.

Note : Always avoid using an

appreciably large blank correction which gives rise to a vague and uncertain

‘exact value’ thereby minimising the precision of the analysis.

(iv) Cross-checking Results by Different Methods

of Analysis

In certain specific cases tha accuracy of a result may be

cross-checked by performing another analysis of the same substance by an

altogether radically different method.

Examples :

(a) HCl-Solution : It may be assayed either

by titration with a standard solution of a strong alkali (NaOH), or by

precipitation and weighing as AgCl ; and

(b) Fe3+ : It may be assayed

either by gravimetric method as Fe(III) hydroxide after getting rid of the

interfering elements and igniting the precipitate to Fe(III) oxide, or by

titrimetric method i.e., first

reducing to the Fe(II) state and then titrating with a suitable oxidizing

agent, for instance Ce(IV) sulphate,

K2Cr2O7. In short, the results thus obtained

by the two fundamen-tally different techniques must be concordant thereby

justifying and ascertaining the fact that the values obtained are fairly small

limits of error.

(v) Method of Standard Addition

Here, a small known quantity of the component under

estimation is added to the sample, which is subsequently subjected to analysis

for the total amount of component present. The actual differ-ence in the

quantity of components present in samples with or without the added component

ultimately gives the recovery of the quantum added component. A good

satisfactory recovery builds up the confidence in the accuracy of the method of

analysis.

Note : The method of ‘standard

addition’ is particularly useful to physicochemical techniques

of analysis, for instance :

spectrophotometry, turbidimetry.

(vi) Method of Internal Standards

The specific method is of immense value both in

chromatographic as well as spectroscopic determinations. Here, a fixed quantity

of a reference substance (i.e., the

‘internal standard’) is added to a series of known concentrations of the

material to be assayed.

A graph is plotted between the concentration values and

the ratios obtained from the physical value (i.e., peak area of absorption) of the ‘internal standard’ and the series of known concentra-tions,

thereby producing a straight line. Any unknown concentration may be determined

effec-tively by adding the same amount of ‘internal

standard’ and locating exactly where the ratio obtained falls on the

concentration scale.

Related Topics