Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Anesthesia for Thoracic Surgery

Anesthesia for Tracheal Resection

Anesthesia for Tracheal Resection

Preoperative Considerations

Tracheal resection is most commonly

performed for tracheal stenosis, tumors, or, less commonly, con-genital

abnormalities. Tracheal stenosis can result from penetrating or blunt trauma,

as well as trachealintubation and tracheostomy. Squamous cell and adenoid

cystic carcinomas account for the major-ity of tumors. Compromise of the

tracheal lumen results in progressive dyspnea. Wheezing or stridor may be

evident only with exertion. The dyspnea may be worse when the patient is lying

down, with progressive airway obstruction. Hemoptysis can also complicate

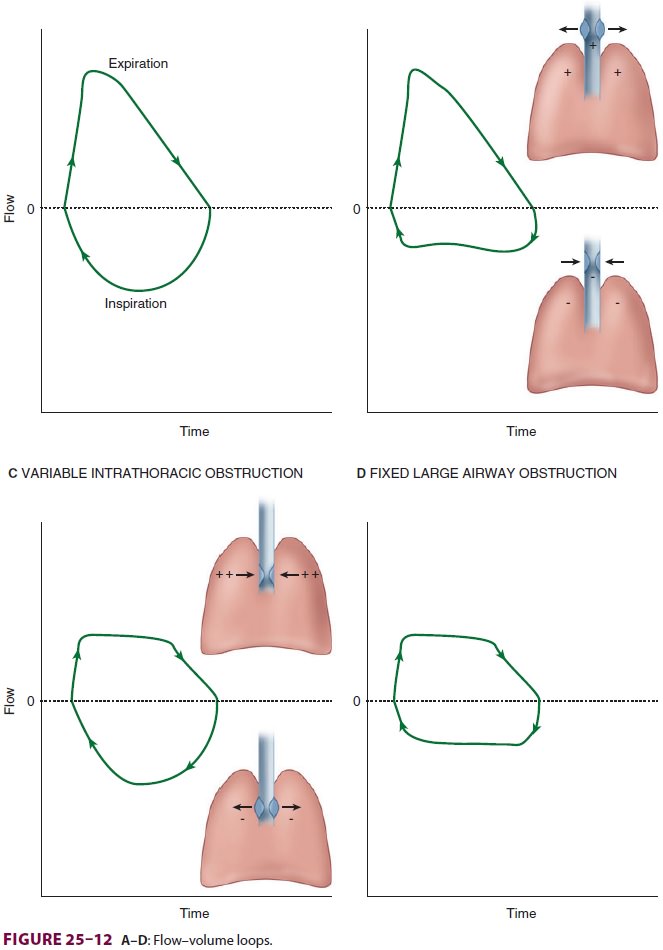

tracheal tumors. CT is valuable in localizing the lesion. Measurement of flow–volumeloops

confirms the location of the obstruction and aids the clinician in evaluating the severity of the lesion (Figure25–12).

Anesthetic Considerations

Little premedication is given, as most

patients pre-senting for tracheal resection have moderate to severe airway

obstruction. Use of an anticholinergic agent to dry secretions is controversial

because of the theoretical risk of inspissation. Monitoring should include

direct arterial pressure measurements.

An inhalation induction (in 100% oxygen)

is carried out in patients with severe obstruction. Sevoflurane is preferred

because it is the potent anesthetic that is least irritating to the airway.

Spontaneous ventilation is maintained throughout induction. NMBs are generally

avoided because of the potential for complete airway obstruction follow-ing

neuromuscular blockade. Laryngoscopy is per-formed only when the patient is

judged to be under deep anesthesia. Intravenous lidocaine (1–2 mg/kg) can deepen the anesthesia without

depressing respi-rations. The surgeon may then perform rigid bron-choscopy to

evaluate and possibly dilate the lesion. Following bronchoscopy, the patient is

intubated with a tracheal tube small enough to be passed distal to the

obstruction whenever possible.

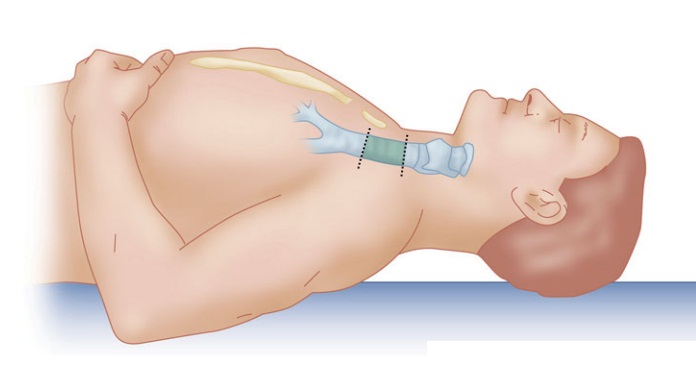

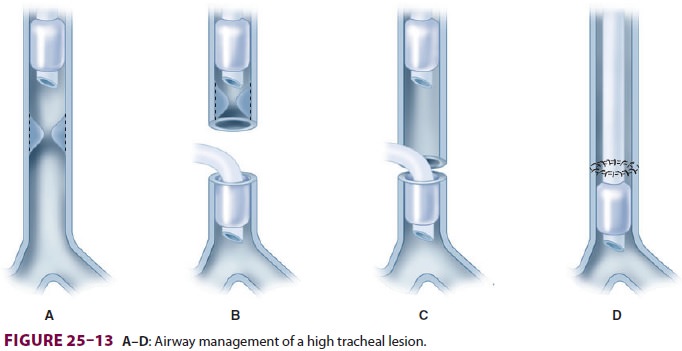

A collar incision is utilized for high

tracheal lesions. The surgeon divides the trachea in the neck and advances a

sterile armored tube into the distal trachea, passing off a sterile connecting

breathing circuit to the anesthesiologist for ventilation during the resection.

Following the resection and comple-tion of the posterior part of the

reanastomosis, the armored tube is removed, and the original tracheal tube is

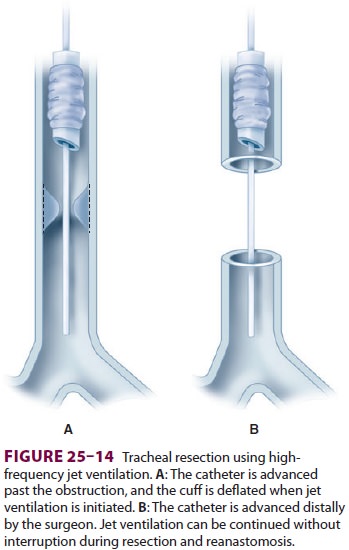

advanced distally, past the anastomosis (Figure25–13). Alternatively, high-frequency jet

ventilation may be employed during the anastomosis

by passing the jet cannula past the

obstruction and into the distal trachea ( Figure25–14). Return of spontaneous ventilation and

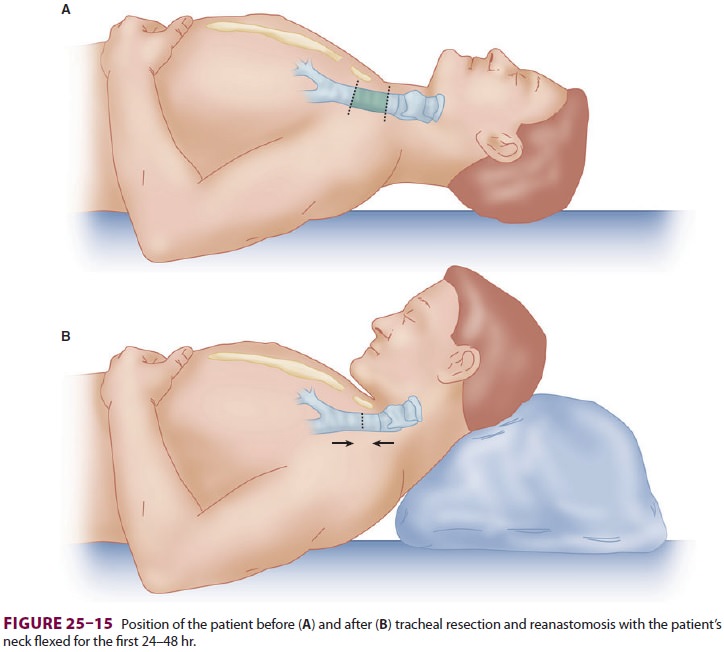

early extubation at the end of the procedure are desirable. Patients should be

positioned with the neck flexed immediately after the operation to minimize

tension on the suture line (Figure25–15).

Surgical management of low tracheal

lesions requires a median sternotomy or right posterior thoracotomy. Anesthetic

management is similar, but more regularly requires more complicated tech-niques,

such as high-frequency ventilation or even cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) in

complex congen-ital cases.

Related Topics