Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Anesthesia for Thoracic Surgery

Anesthesia for Lung Resection: Preoperative Considerations

Anesthesia for Lung Resection

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Lung resections are usually carried out

for the diag-nosis and treatment of pulmonary tumors, and, less commonly, for

complications of necrotizing pulmo-nary infections and bronchiectasis.

1. Tumors

Pulmonary tumors can be either benign or

malig-nant, and, with the widespread use of bronchoscopic sampling, the

diagnosis is usually available prior to surgery. Hamartomas account for 90% of

benign pulmonary tumors; they are usually peripheral pul-monary lesions and

represent disorganized normal pulmonary tissue. Bronchial adenomas are usually

central pulmonary lesions that are typically benign, but occasionally may be

locally invasive and rarely metastasize. These tumors include pulmonary

car-cinoids, cylindromas, and mucoepidermoid adeno-mas. They often obstruct the

bronchial lumen and cause recurrent pneumonia distal to the obstruction in the

same area. Primary pulmonary carcinoids may secrete multiple hormones,

including adrenocortico-tropic hormone (ACTH) and arginine vasopressin;

however, manifestations of the carcinoid syndrome are uncommon and are more

likely with metastases.Malignant pulmonary tumors are divided into small

(“oat”) cell and non–small cell carcinomas.The latter group includes squamous

cell (epider-moid) tumors, adenocarcinomas, and large cell (anaplastic) carcinomas.

All types are more com-monly encountered in smokers, but more “never smokers”

die of lung cancer each year in the United States than the total number of

people who die of ovarian cancer. Epidermoid and small cell carcino-mas usually

present as central masses with bronchial lesions; adenocarcinoma and large cell

carcinomas are more typically peripheral lesions that often involve the pleura.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms may include cough, hemoptysis,

wheez-ing, weight loss, productive sputum, dyspnea, or fever. Pleuritic chest

pain or pleural effusion sug-gests pleural extension. Involvement of

mediastinal structures is suggested by hoarseness that results from compression

of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, Horner’s syndrome caused by involvement of

the sympathetic chain, an elevated hemidiaphragm caused by compression of the

phrenic nerve, dys-phagia caused by compression of the esophagus, or the

superior vena cava syndrome caused by compression or invasion of the superior

vena cava. Pericardial effusion or cardiomegaly suggests car-diac involvement.

Extension of apical (superior sulcus) tumors can result in either shoulder or

arm pain, or both, because of involvement of the C7–T2 roots of the brachial

plexus (Pancoast syndrome). Distant metastases most commonly involve the brain,

bone, liver, and adrenal glands.

Treatment

Surgery is the treatment of choice to

reduce the tumor burden in nonmetastatic lung cancer. Various chemotherapy and radiation

treatments are likewise employed, but there is wide variation among tis-sue

types in their sensitivity to chemotherapy and radiation.

Resectability & Operability

Resectability is determined by the

anatomic stage of the tumor, whereas operability is dependent on the

interaction between the extent of the procedure required for cure and the

physiological status of the patient. Anatomic staging is accomplished using

chest radiography, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI), bronchoscopy, and (sometimes) mediastinoscopy. The extent of the surgery

should maximize the chances for a cure but still allow for adequate residual

pulmonary function postoperatively. Lobectomy via a posterior thora-cotomy,

through the fifth or sixth intercostal space, or thorough video assisted

thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), is the procedure of choice for most lesions.

Segmental or wedge resections may be performed in patients with small

peripheral lesions and poor pul-monary reserve. Pneumonectomy is necessary for

curative treatment of lesions involving the left or right main bronchus or when

the tumor extends toward the hilum. A sleeve resection may be employed for

patients with proximal lesions and limited pulmonary reserve as an alternative

to pneumonectomy; in such instances, the involved lobar bronchus, together with

part of the right or left main bronchus, is resected, and the distal bronchus

is reanastomosed to the proximal bronchus or the trachea. Sleeve pneumonectomy

may be considered for tumors involving the trachea.

The incidence of pulmonary complications

after thoracotomy and lung resection is about 30% and is related not only to

the amount of lung tis-sue resected, but also to the disruption of chest wall

mechanics due to the thoracotomy. Postoperative pulmonary dysfunction seems to

be less after VATS than “open”

thoracotomy. The mortality rate for pneumonectomy is generally more than twice

that of for a lobectomy. Mortality is greater for right-sided than left-sided

pneumonectomy, possibly because of greater loss of lung tissue.

Evaluation for Lung Resection

A comprehensive preoperative pulmonary

assess-ment is necessary to assess the operative risk, minimize perioperative

complications, and achieve better outcomes. Preoperative assessment of

respi-ratory function includes determinations of respira-tory mechanics, gas

exchange, and cardiorespiratory interaction.Respiratory mechanics are assessed

by pulmo-nary function tests. Of these parameters, the most useful is the

predicted postoperative forced expira-tory volume in one sec (FEV1), which is calculated as follows:

Postoperative FEV1 = preoperative FEV1 × (1 – the percentage of functional lung tissue

removed divided by 100)

Removal of extensively diseased lung

(nonven-tilated but perfused) does not necessarily adversely affect pulmonary

function and may actually improve oxygenation. Mortality and morbidity are

signifi-cantly increased if postoperative FEV1 is less than 40% of normative FEV1, and patients with predicted postoperative FEV1 of less than 30% may need post-operative mechanical

ventilatory support.Gas exchange will sometimes be characterized by diffusion

lung capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO). DLCO correlates with the total

function-ing surface area of the alveolar–capillary interface. Predictive

postoperative DLCO can be calculated in the same fashion as postoperative FEV1. A predicted postoperative DLCO of less than 40%

also corre-lates with increased postoperative respiratory and cardiac

complications. Adequacy of gas exchange is more commonly assessed by

arterialblood gas data such as Pao2 >60 mm Hg and· a Pa·co2 <45 mm Hg.

Ventilation-perfusion(V/Q)scintigraphy

pro-vides the relative contribution of each lobe to over-all pulmonary function

and may further refine the assessment of predicted postoperative lung function,

in patients where pneumonectomy is the indicated surgical procedure and there

is concern whether a single lung will be adequate to support life.

Patients considered at greater risk of

periop-erative complications based on standard spirometry testing and

calculation of postoperative function should undergo exercise testing for

evaluation of

cardiopulmonary interaction. Stair

climbing is the easiest way to assess exercise capacity and cardio-pulmonary

reserve. Patients capable of climbing two or three flights of stairs have

decreased mortal-ity and morbidity. On the other hand, the ability to climb

less than two flights of stairs is associated with increased perioperative

risk. The gold standard for evaluating cardiopulmonary interaction is by

labo-ratory exercise testing and measurement of maximal minute oxygen consumption.

A V˙o2>20 mL/kg is not associated with a significant increase in

peri-operative mortality or morbidity, whereas a minute consumption of less

than 10 mL/kg is associated

with an increased perioperative risk.

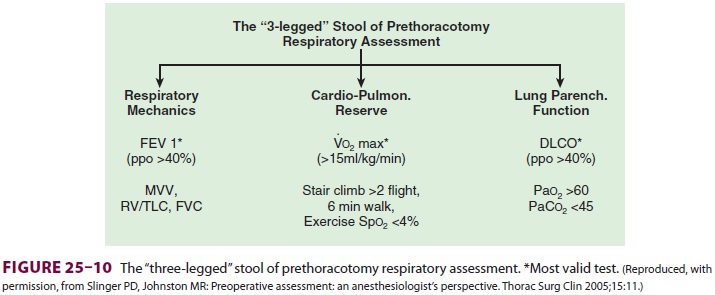

A combination of tests to evaluate the

three components of the respiratory function (ie, respira-tory mechanics, gas

exchange, and cardiopulmonary interaction) has been summarized in the so-called

“three-legged” stool of respiratory assessment (Figure25–10).

2. Infection

Pulmonary infections may present as a

solitary nod-ule or cavitary lesion (necrotizing pneumonitis). An exploratory

thoracotomy may be carried out to exclude malignancy and diagnose the

infectious agent. Lung resection is also indicated for cavitary lesions that

are refractory to antibiotic treatment, are associated with refractory empyema,

or result inmassive hemoptysis. Responsible organisms include both bacteria and

fungi.

3. Bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis is a permanent dilation

of bronchi. It is usually the end result of severe or recurrent inflammation

and obstruction of bronchi. Causes include a variety of viral, bacterial, and

fungal patho-gens, as well as inhalation of toxic gases, aspiration of gastric

acid, and defective mucociliary clearance (cystic fibrosis and disorders of ciliary

dysfunction). Bronchial muscle and elastic tissue are typically replaced by

very vascular fibrous tissue. The lat-ter predisposes to bouts of hemoptysis.

Pulmonary resection is usually indicated for massive hemopty-sis when

conservative measures have failed and the disease is localized. Patients with

diffuse bronchiec-tasis have a chronic obstructive ventilatory defect.

Related Topics