Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Musculoskeletal Trauma

Pelvis - Fracture

PELVIS

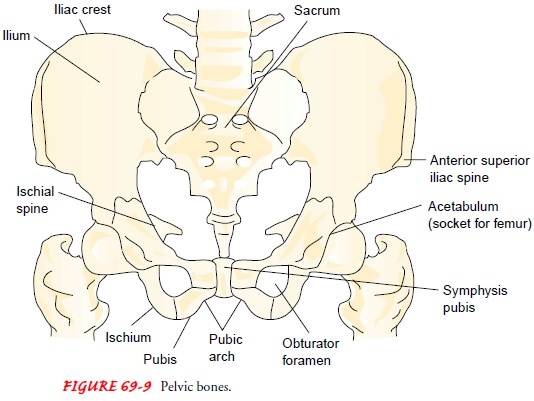

The sacrum, ilium,

pubis, and ischium bones form the pelvic bone, a fused, stable, bony ring in

adults (Fig. 69-9). Falls, motor vehicle crashes, and crush injuries can cause

pelvic fractures. Pel-vic fractures are serious because at least two thirds of

affected patients have significant and multiple injuries. Management of severe,

life-threatening pelvic fractures is coordinated with the trauma team.

Hemorrhage and thoracic, intra-abdominal, and cranial injuries have priority

over treatment of fractures. There is a high mortality rate associated with

pelvic fractures, related to hemorrhage, pulmonary complications, fat emboli,

intravascular coagulation, thromboembolic complications, and infection.

Pelvic fracture symptoms

include ecchymosis; tenderness over the symphysis pubis, anterior iliac spines,

iliac crest, sacrum, or coccyx; local swelling; numbness or tingling of pubis,

genitals, and proximal thighs; and inability to bear weight without

dis-comfort. Computed tomography of the pelvis helps to determinethe extent of

injury by demonstrating sacroiliac joint disruption, soft tissue trauma, pelvic

hematoma, and fractures. Neurovascular assessment of the lower extremities is

completed to detect injury to pelvic blood vessels and nerves.

Hemorrhage and shock are

two of the most serious consequen-ces that may occur. Bleeding arises from the

cancellous surfaces of the fracture fragments, from laceration of veins and

arteries by bone fragments, and possibly from a torn iliac artery. The

peripheral pulses of both lower extremities are palpated; absence of pulses may

indicate a torn iliac artery or one of its branches. Peritoneal lavage may be

performed to detect intra-abdominal hemorrhage. The patient is handled gently

to minimize further bleeding and shock.

The nurse assesses for injuries to the bladder, rectum,

intes-tines, other abdominal organs, and pelvic vessels and nerves. To assess

for urinary tract injury, the patient’s urine is examined for blood. A voiding

cystourethrogram and an intravenous urogram may be performed. Laceration of the

urethra is suspected in males with anterior fracture of the pelvis and blood at

the urethral me-atus. (Females rarely experience a lacerated urethra.) A

catheter should not be inserted until the status of the urethra is known.

Abdominal pain and signs of peritonitis suggest injury to the in-testines or

abdominal bleeding. Paralytic ileus may accompany pelvic fractures.

Numerous classification

systems have been used to describe pelvic fractures in relation to anatomy,

stability, and mechanism of injury. Some fractures of the pelvis do not disrupt

the pelvic ring; others disrupt the ring, which may be rotationally or

verti-cally unstable. The severity of pelvic fractures varies. Long-term

complications of pelvic fractures include malunion, nonunion, residual gait

disturbances, and back pain from ligament injury.

Stable Pelvic Fractures

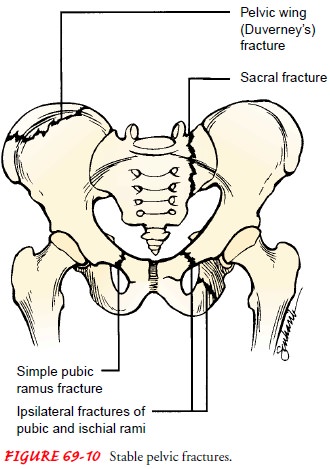

Stable fractures of the

pelvis (Fig. 69-10) include fracture of a single pubic or ischial ramus,

fracture of ipsilateral pubic and ischial rami, fracture of the pelvic wing of

ilium (ie, Duverney’s fracture), and fracture of the sacrum or coccyx. Also, if

injury results in only a slight widening of the pubic symphysis or the anterior

sacroiliac joint and the pelvic ligaments are intact, the disrupted pubic sym-physis

is likely to heal spontaneously with conservative manage-ment. Most fractures

of the pelvis heal rapidly because the pelvic bones are mostly cancellous bone,

which has a rich blood supply.

Stable pelvic fractures are treated with a few days of

bed rest and symptom management until the pain and discomfort are con-trolled.

The patient on bed rest is at risk for complications from immobility, including

constipation, venous stasis, and pulmonary complications. Fluids, dietary

fiber, ankle and leg exercises, elastic compression stockings to aid venous

return, log rolling, coughing and deep breathing, and skin care reduce the risk

for complica-tions and increase the patient’s comfort. The patient with a

frac-tured sacrum is at risk for paralytic ileus, and bowel sounds should be

monitored.

The patient with fracture of the coccyx experiences pain

on sitting and with defecation. Sitz baths may be prescribed to re-lieve pain,

and stool softeners may be given to prevent the need to strain on defecation.

As pain resolves, activity is gradually resumed with the use of ambulatory aids

(eg, crutches, walker) for protected weight bearing. Early mobilization reduces

problems related to immobility.

Unstable Pelvic Fractures

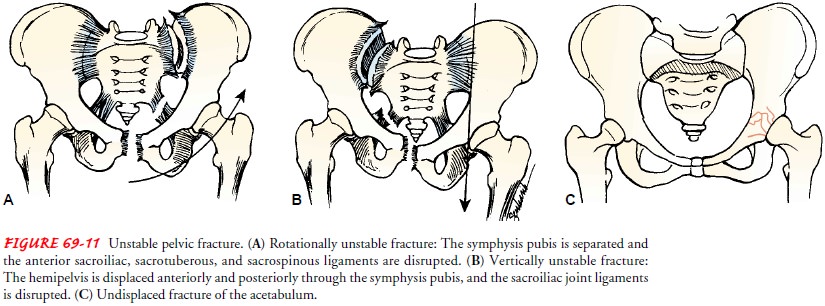

Unstable fractures of

the pelvis (Fig. 69-11) may result in rotational instability (eg, the open book

type, in which a separation occurs at the symphysis pubis with some sacral

ligament disruption), vertical instability (eg, the vertical shear type, with

superior–inferior dis-placement), or a combination of both. Lateral or

anterior–posterior compression of the pelvis produces rotationally unstable

pelvic frac-tures. Vertically unstable pelvic fractures occur when force is exerted

on the pelvis vertically, as when the person falls from a height onto extended

legs or is struck from above by a falling object. Vertical shear pelvic

fractures involve the anterior and posterior pelvic ring with vertical

displacement, usually through the sacroiliac joint. There is generally complete

disruption of the posterior sacroiliac, sacrospinous, and sacrotuberous

ligaments. Vertical displacement of the hemipelvis is usually evident.

Treatment of unstable pelvic fractures generally involves

ex-ternal fixation or open reduction and internal fixation. This pro-motes

hemostasis, hemodynamic stability, comfort, and early mobilization.

Acetabulum

Fractures of the

acetabulum are seen after motor vehicle crashes in which the femur is jammed

into the dashboard. Treatment depends on the pattern of fracture. Stable,

nondisplaced fractures and frac-tures that involve minimal articular weight

bearing may be managed with traction and protective (toe touch) weight bearing.

Displaced and unstable acetabular fractures are treated with open reduction,

joint débridement, and internal fixation or arthroplasty. Internal fixation

permits early non–weight-bearing ambulation and ROM exercise. Complications

seen with acetabular fractures include nerve palsy, heterotopic ossification,

and posttraumatic arthritis.

Related Topics