Chapter: Medicine and surgery: Haematology and clinical Immunology

Malaria

Malaria

Definition

Malaria is an infection caused by one of the four species of the genus Plasmodium.

Incidence

Worldwide there are 300–500 million cases of malaria per year with a mortality rate of up to 1%. In the United Kingdom there are 1500–2000 cases per year, most of which are caused by Plasmodium falciparum. The incidence in the United Kingdom is rising.

Geography

Endemic malaria is found in parts of Asia, Africa, Central and South America, Oceania and certain Caribbean islands. In the United Kingdom, travellers to these areas who do not take adequate precautions are at greatest risk.

Aetiology

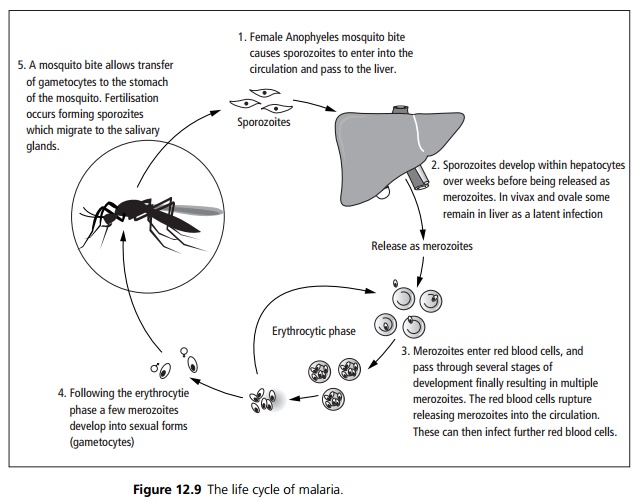

Four species of Plasmodium affect humans: P. falciparum, P. malariae, P. ovale and P. vivax. Transmission occurs predominantly by the bite of the female Anopheles mosquito although transmission may occur by blood transfusion or transplacentally. The life cycle of malaria is shown in Fig. 12.9.

Pathophysiology

Parasites consume red cell proteins, glucose and haemoglobin. They affect the red cell membrane making the cell less deformable and ultimately causing cell lysis. Falciparum induces cell surface adhesion molecules on red cells causing adhesion to small vessels and uninfected red cells. This leads to occlusion within the microcirculation and organ dysfunction. Resistance to malaria is conferred by genetic variation:

· The Duffy red cell antigen is necessary for invasion by P. vivax. Many Africans do not express this antigen and have a relative resistance.

· The sickle cell gene reduces mortality in P. falciparum infections.

· α thalassaemia increases susceptibility to P. vivax reducing subsequent P. falciparum infection.

· β thalassaemia reduces parasite multiplication due to the persistence of fetal haemoglobin which is resistant to digestion by malaria.

Symptoms are associated with the asexual stages. In the gametocyte stage there is genetic recombination causing antigenic variation.

Clinical features

Most patients have a history of recent travel to an endemic area. Patients develop symptoms including cough, fatigue, malaise, spiking fever and rigors, arthralgia and myalgia. The classical description of paroxysmal chills and shivering followed by a spike of high temperature is only seen in the minority of patients. Other symptoms include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and headache. Examination may reveal tachycardia, pyrexia, hypotension, pallor and in chronic cases splenomegaly. There should be a high index of suspicion for malaria in any patient presenting with symptoms following travel to endemic areas.

Complications

P. falciparum is potentially life threatening due to cerebral malaria (progressive headache, neck stiffness, convulsions and coma), severe anaemia (red cell lysis and reduced erythropoesis), hypoglycaemia, hepatic and renal failure. It may also lead to severe intravascular haemolysis causing dark brown/black urine (blackwater fever) particularly after treatment with quinine.

Investigations

Diagnosis is by identification of parasites on thick and thin blood films. Although the first specimen is positive in 95% of cases at least three negative samples are required to exclude the diagnosis. The thick film is more sensitive for diagnosis and the thin film is used to differentiate the parasites and quantify the percentage of parasite infected cells. Other diagnostic tests include ELISA antigen detection and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests. Other investigations should include a full blood count, U&E, liver function tests, clotting, urine and blood cultures. If there are signs of neurological involvement a CT scan of the head should be performed but should not delay treatment.

Management

If causative species is not known, or if the infection is mixed, initial treatment should be as for P. falciparum.

P. falciparum is treated by oral quinine, mefloquine, Malarone (proguanil and atovaquone), or Riamet (artemether with lumefantrine). If the patient is unable to swallow, is vomiting or has impaired consciousness intravenous quinine is used. Falciparum malaria can progess rapidly in unprotected individuals. Treatment should be considered in patients with features of severe malaria even if the initial blood tests are negative. Other supportive treatments include monitoring for, and correction of hypoglycaemia, blood transfusion for severe anaemia. In severe cases intensive care may be required.

Benign malaria (P. vivax P. ovale or P. malariae) is treated with chloroquine although some P. vivax is developing resistance. P. malariae and ovale require subsequent treatment with primaquine to eradicate latent parasites in the liver (after exclusion of G6PD deficiency).

Chemoprophylaxis is dependent on the area that is to be visited and specialist advice should be sought. In general where there is no chloroquine resistance weekly chloroquine is used. In areas of chloroquine resistance a combination of chloroquine and proguanil may be used. Alternative regimes include mefloquine, Maloprim (dapsone and pyrimethamine) or doxycycline. Prophylaxis should begin prior to entering an endemic area (in order to detect establish tolerance) and should continue for 4 weeks after leaving the endemic areas. Mosquito repellent nets and sprays, and protective clothing should also be used.

Related Topics