Chapter: The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology: Fishes as social animals: reproduction

Alternative mating systems and tactics - Fishes as social animals

Alternative mating systems and tactics

The literature on social and reproductive behavior in fishes has increasingly focused on the variety of tactics that fishes use, both among and within species. That interspecific differences should arise is not surprising given the different ecologies and evolutionary histories of different lineages. Intraspecific variation is more puzzling, since we tend to think in terms of species characteristics and “species-typical” behavior.

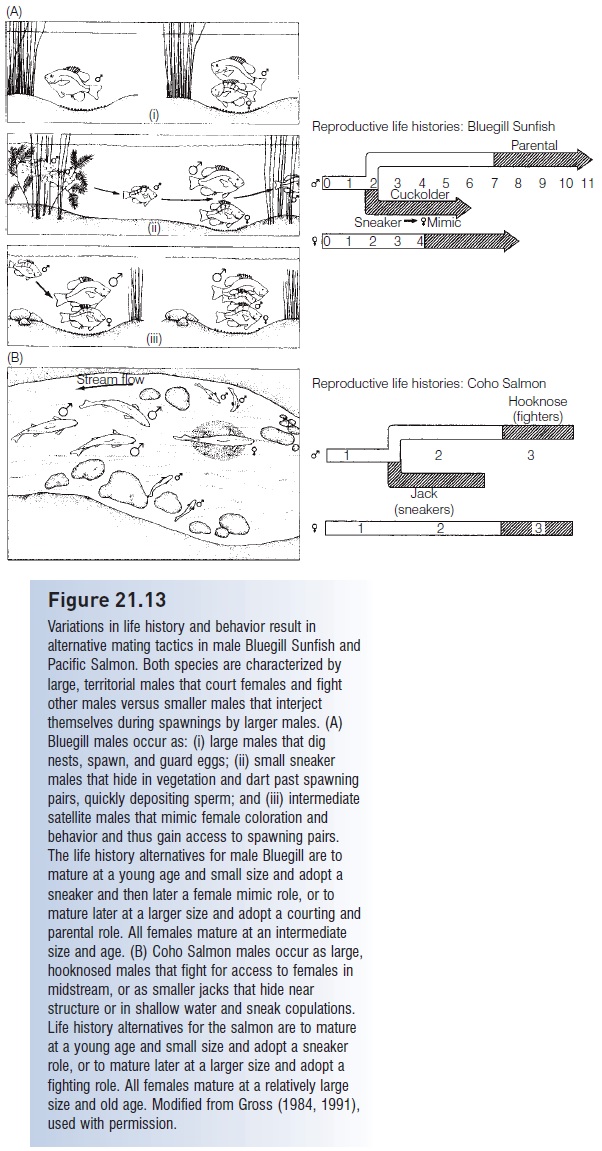

In addition to initial and terminal males in sex-changing wrasses, small alternative males also exist among gonochoristic fishes such as minnows, salmons, midshipmen, sticklebacks, livebearers, topminnows, sunfishes, cichlids, wrasses, blennies, and gobies (Taborsky 1994) (Fig. 21.13). In the Bluegill Sunfish, Lepomis macrochirus, larger, older parental males (17 cm long, 8.5 years old) construct nests, court females, and then guard the eggs that they fertilize. Two

Satellite males are intermediate in size and age (9 cm, 4 years old); they mimic female coloration and behavior and hence gain access to a nest, interposing themselves between the parental male and the female during spawning. Smaller, sneaker males (7 cm, 3 years old) lurk in nearby vegetation and dart through nests during spawnings, depositing sperm literally on the run. These three options arise from two discrete alternative life histories: parental males that delay maturation, grow large, and begin spawning when they are older than 7 years old versus cuckolder males that mature as small 2-year-olds, acting first as sneakers and then later (when they achieve the size of reproductive females) as satellite males. Cuckoldry becomes a viable alternative only when parental males are abundant because parental males provide the breeding opportunity (Gross 1984).

Pacific salmons of the genus Oncorhynchus demonstrate an analogous pattern (Fig. 21.13). Male Coho Salmon, O. kisutch, occur as two types in spawning streams. Large (52 cm long, 2.5 years old), colorful hooknose males court the females that have dug linear nests (redds) in the gravel bottom. Breeding success is directly related to male size and proximity to females; larger fish fi ght successfully to be closest and thereby spawn most. A second group of males, called jacks, are smaller and younger (34 cm long, 1.5 years old). These males hide in nearby stream debris and dash onto the redd as the hooknoses are spawning with females. Intermediate-size fish are relatively rare, probably because they are too small to fi ght successfully and too large to hide successfully. Again, sneaking provides a spawning opportunity for small males that otherwise could not compete with large males for access to females (Gross 1984).

In both examples, it is still unknown whether the alternative tactics are brought about by genetic or environmental influences or a combination of the two. Are cuckolders and jacks genetically programmed to behave as such, do they develop in response to immediate environmental conditions – including the density of larger, parental or hooknose fish – or do genes and environment combine to determine proportions of males? A combination of influences is indicated by the salmon data. Jacks develop from fish that grow faster when young. Clearcutting around

Figure 21.13

Variations in life history and behavior result in alternative mating tactics in male Bluegill Sunfish and Pacific Salmon. Both species are characterized by large, territorial males that court females and fight other males versus smaller males that interject themselves during spawnings by larger males. (A) Bluegill males occur as: (i) large males that dig nests, spawn, and guard eggs; (ii) small sneaker males that hide in vegetation and dart past spawning pairs, quickly depositing sperm; and (iii) intermediate satellite males that mimic female coloration and behavior and thus gain access to spawning pairs. The life history alternatives for male Bluegill are to mature at a young age and small size and adopt a sneaker and then later a female mimic role, or to mature later at a larger size and adopt a courting and parental role. All females mature at an intermediate size and age. (B) Coho Salmon males occur as large, hooknosed males that fight for access to females in midstream, or as smaller jacks that hide near structure or in shallow water and sneak copulations. Life history alternatives for the salmon are to mature at a young age and small size and adopt a sneaker role, or to mature later at a larger size and adopt a fighting role. All females mature at a relatively large size and old age. Modified from Gross (1984, 1991), used with permission.

Alternative mating tactics representing variations on the above patterns exist in other fishes (e.g., Fallfish Minnows, cichlids, Peacock Wrasses, blennies, gobies; Ross 1983; Van den Berghe 1988; Barlow 1991; Magnhagen 1992; Henson & Warner 1997; Taborsky 2001; Neat et al. 2003). Why fishes are so labile in mating and life history patterns is problematic. In many instances, the existence of one pattern creates the conditions that favor the development of the other: sneakers depend on territorial males to provide them with breeding opportunities. However, sneaking is negatively frequency dependent in that, because of competition, the advantages of sneaking decrease as the density of sneakers increases. Alternatively, no single strategy may confer a consistently greater selective advantage over others, so each is favored at different times and is consequently maintained at least at low frequencies in a population. Finally, differing reproductive modes may represent nothing more than alternative, equally adaptive responses to similar environmental forces (Fischer & Petersen 1987).

Related Topics