Chapter: Surgical Pathology Dissection : The Female Genital System

Uterus, Cervix and Vagina : Surgical Pathology Dissection

Uterus, Cervix and Vagina

Biopsies

Cervical

and vaginal biopsies consist of an epithe-lial surface and varying amounts of

underlying stroma. Usually, no grossly identifiable lesion can be seen. The

most important objectives are to orient the specimen so that perpendicular

sec-tions will be taken through the surface and to secure the specimen properly

to ensure that small pieces are not lost. These tasks can be accom-plished in

several ways. If the specimen is large enough (i.e., greater than 0.4 cm), the

tissue can be bisected perpendicular to the surface and marked with either

mercurochrome or tattoo powder to indicate the surface to be cut. If the

specimen is small, it can be secured between Gel-foam sponges, within fine-mesh

biopsy bags, or it can be wrapped in tissue paper. The gynecolo-gist may also

submit the biopsy oriented mucosal side up on a mounting surface such as filter

paper. In this case, instruct your histotechnologist to embed and cut the

biopsy specimen perpendic-ular to the mounting surface. All biopsy speci-mens

should be entirely submitted, and it is often useful to routinely request that

multiple levels be examined by the histology laboratory.

Endometrial

biopsies should be handled simi-larly to curettage specimens.

Curettings

Endocervical

and endometrial curettings consist of multiple small fragments of epithelium,

which are often admixed with blood and mucus. The surgeon may put the

curettings on Telfa pads or directly into fixative. Scrape the Telfa pad

care-fully on both sides, and filter the fluid of the speci-men container into

a tissue bag to obtain all tissue fragments. Record the aggregate dimension,

and note the percentage of tissue versus the percent-age of blood and mucus.

The entire specimen should be submitted either wrapped in tissue paper or

within a fine-mesh biopsy bag. Even if no tissue is visible, the blood and

mucus should still be submitted for histologic evalua-tion, as they may contain

entrapped small epithe-lial fragments. Multiple levels are often useful in

evaluating these specimens. For endometrial specimens, if the tissue obtained

is not repre-sentative of functioning endometrium (e.g., endocervix, lower

uterine segment, or surface endometrial epithelium only), this fact should be

specified. If endometrial cancer is identified, estimate the percentage of the

specimen in-volved by tumor.

Cervix

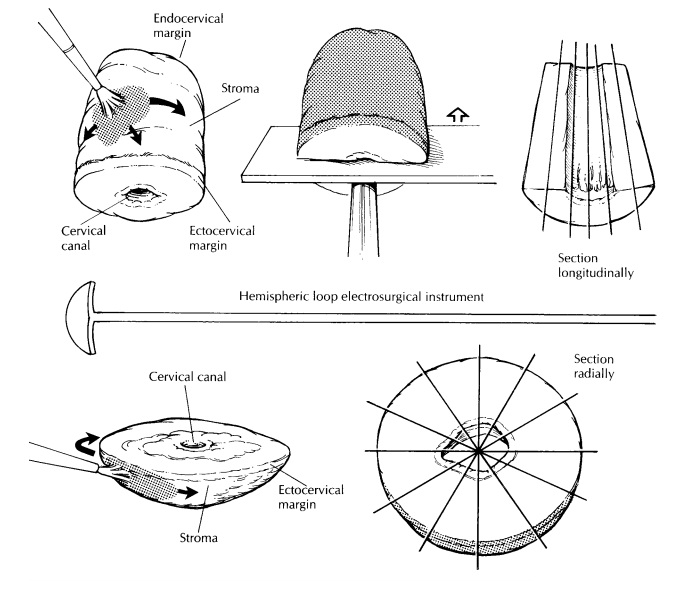

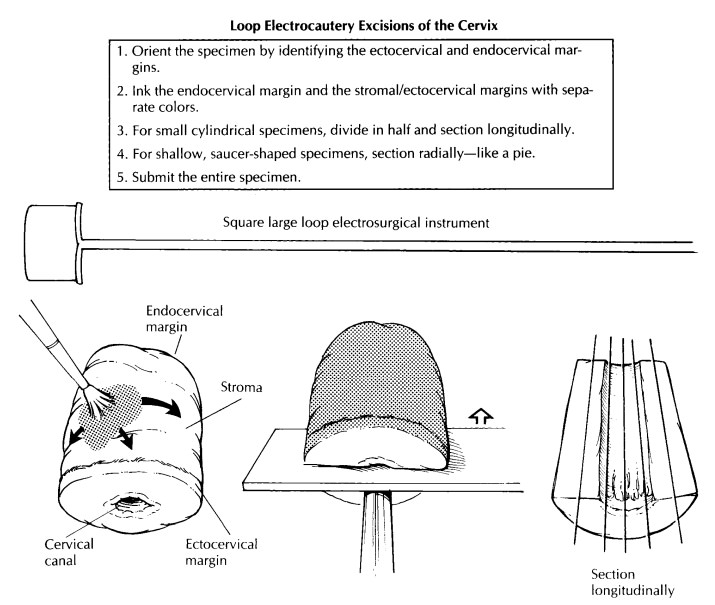

Loop Electrocautery Excisions

The loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) and large loop excision of the transforma-tion zone (LLETZ) are electrocautery excisions of the cervical transformation zone that excise less tissue than the traditional cone biopsy. Their use is increasing in the treatment of squamous intraepithelial lesions. Depending on the type of loop used and on the depth of the excision, the specimen may be large enough to allow one to orient, open, and process it like a conventional cone biopsy, as described later.

However, many of these specimens arrive in the

surgical pathol-ogy laboratory already fixed in formalin and/or in several

pieces. The endocervical margin will sometimes be submitted separately, and an

overall orientation may or may not be provided. If multiple fragments are

submitted, identify the mucosal surface, and try to distinguish the smooth,

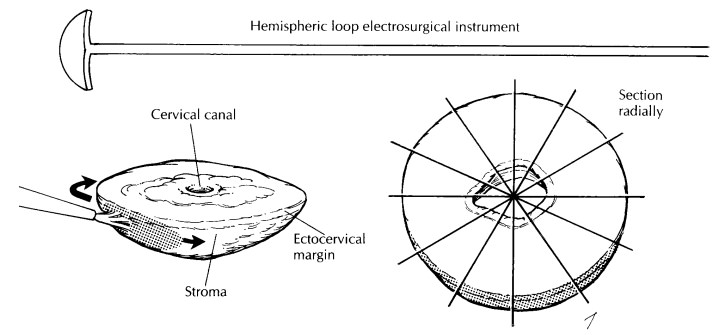

gray squamous mucosa from the ru-gated, mucoid, tan endocervical mucosa. Divide

the fragments into strips with sections perpen-dicular to the squamocolumnar

junction. For shallow, saucer-shaped specimens, divide the specimen radially as

illustrated. This is similar to slicing a pie. For small conical specimens that

are already well fixed, divide the specimen into anterior and posterior halves,

and section each half longitudinally as shown. Conceptually, cut-ting the biopsy

this way is similar to the handling of the perpendicular sections of the distal

urethral margins in a radical prostatectomy specimen. Note that in contrast to

large cone biopsies, not all sections will demonstrate the cervical canal

mucosa. Although cautery artifact may make the limits of resection of these

specimens difficult to evaluate, it is always best to ink the mucosal margins

and exposed stroma for histologic evaluation.

Cone Biopsy

A cervical cone biopsy is a conical excision of the cervical canal performed with either a laser or a surgical blade (cold knife excision). The wider part of the cone is the outer ectocervix, and the tapered end is the endocervical margin. Mea-sure the length of the cone biopsy corresponding to the endocervical canal, the diameter at the ectocervical margin, and the diameter at the en-docervical margin. By convention, the ectocervix is described as a clock face with the most superior midpoint of the anterior lip designated as 12 o’clock. This point is usually marked with a stitch by the gynecologist. After orienting the cone biopsy as if viewed in situ, ink the exposed fibrous stroma and the ectocervical mucosal margin. Use a different color to ink the endocervical mucosal margin. Make a longitudinal incision through the outer stroma to the inner canal at the 3-o’clock position, and open the specimen so that the inner mucosal surface is exposed. The convention of incising the cervix at either 3 or 9 o’clock is based on the fact that most cervical lesions arise on the anterior and posterior surfaces, rather than laterally. Pin the specimen to either a wax or cork board with the epithelial surface upward, using pins placed through the stroma on both sides. Examine the mucosal surface, and look for any lesions, especially along the squamocolumnar junction.

![]()

After

fixation, cut serial full-thickness sections perpendicular to the mucosal

surface in the plane of the endocervical canal. Use the endocervical apex as a

pivot, and angle the cuts to provide a continuous line from the endocervical

mucosa to the ectocervical mucosa. These cuts will en-compass the

squamocolumnar junction and will demonstrate the extent of the transformation

zone. The sections should be 0.2 to 0.3 cm wide and will end up being slightly

wedge-shaped. All sections should be submitted sequentially and designated as

to their clock-face orientation. As with other biopsies, multiple levels are

often routinely requested.

Important Issues to Address in Your Surgical Pathology Report on the Cervix

· What

procedure was performed, and what structures/organs are present?

· What

grade of squamous intraepithelial lesion is identified?

· Is

adenocarcinoma in situ present?

· Is the

lesion focal, multifocal, or extensive? State the percentage or quadrants of

tissue involved.

· Are the

resection margins involved (endocer-vical, ectocervical or stromal)?

· Is

evidence of invasion present? If so, what is the depth of invasion from the

base of the epithe-lium, either surface or glandular, from which it arises (in

millimeters)? What is the horizontal spread (in millimeters)? Is there any

evidence of capillary–lymphatic space invasion?

· If no

precursor lesion or invasive tumor is iden-tified, what is the adequacy of the

specimen (i.e., state the presence or absence of the squamoco-lumnar junction)?

Related Topics