Chapter: Surgical Pathology Dissection : The Female Genital System

Ovary and Fallopian Tube : Surgical Pathology Dissection

Ovary and Fallopian Tube

Ovarian Biopsies and Wedge Resections

Biopsies

and wedge resections of the ovary are infrequently performed procedures that

are used primarily for the evaluation of infertility. Biop-sies should be

measured, briefly described as to color and texture, and submitted in their

entirety. Wedge resections should also be weighed and evaluated for capsule

thickening, ‘‘powder burns’’ of endometriosis, subcortical cysts, and yellow

stromal nodularity indicating hyperthe-cosis. Sections should be taken

perpendicular to the ovarian surface to demonstrate the rela-tionship of the

capsule, cortex, and medulla.

Salpingectomies

Fallopian

tubes can be removed in part or in total. Partial salpingectomies are commonly

performed for tubal sterilization. Total salpingectomies are performed for

ectopic pregnancies, in conjunc-tion with an oophorectomy, or as part of a

hyster-ectomy specimen. Salpingectomies for primary neoplasms of the fallopian

tube are uncommon.

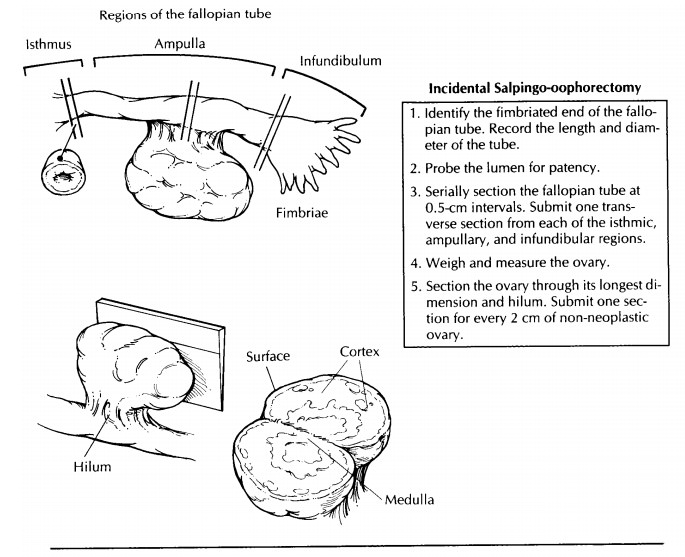

The

evaluation of the incidental salpingectomy specimen is straightforward. The

gross appear-ance of the tube is usually unremarkable. Record the length,

diameter, and color of the tube. De-scribe any features in relationship to the

different portions of the fallopian tube. The intramural portion lies within

the uterus and is not seen in separate salpingectomies. The isthmic portion is

the first 2 to 3 cm external to the uterus. The ampullary portion is the next 5

to 8 cm, and the infundibulum starts where the tube begins to widen and

encompasses the fimbriated end. The patency of the lumen may be tested with a

blunt-tipped probe. Serially section the fallopian tube at 0.5-cm intervals,

and examine it for nodularity, cysts, or masses. Submit one transverse section

from each region.

Small

segments of intervening fallopian tube are usually submitted in tubal

sterilizaton pro-cedures. For legal purposes, a complete cross section of each fallopian tube must be

micro-scopically documented.

Salpingectomies

for ectopic pregnancy should be examined for signs of rupture. Serially section

the fallopian tube, and submit any tissue with the gross appearance of products

of conception. Be sure to include the adjacent wall. If no prod-ucts of

conception are grossly identified, submit several sections from the wall in

regions of hem-orrhage as well as several from the intraluminal clot. In

contrast to uterine products of conception, in which villi are seldom seen

within the blood clots, villi are often identified in the clots from ectopic

pregnancies. Sections of uninvolved fallo-pian tube should also be submitted to

look for evidence of tubal disease contributing to the occurrence of an ectopic

pregnancy (e.g., chronic salpingitis, endometriosis, or salpingitis isth-mica nodosa).

A

salpingectomy for tubal carcinoma should be evaluated in the same manner as an

incidental salpingectomy. In addition, the size, location, and extent of the

tumor should be documented. The maximum depth of tumor penetration can be

evaluated with full-thickness transverse sections of the tube. Margins include

the cut edge of the broad ligament and the proximal fallopian tube end, if not

submitted with the uterus. In the case of a fused tubo-ovarian mass, the

primary site is almost always assumed to be the ovary.

Ovarian Cystectomies and Oophorectomies

Ovarian

cystectomies and oophorectomies are evaluated in a similar manner.

Oophorectomies may be accompanied by the fallopian tube or may be part of a

total hysterectomy specimen. A portion of broad ligament may also be present as

the ovary attaches to the posterior surface of the broad ligament and lies

inferior to the fallo-pian tube.

Incidental

oophorectomies are easily handled. Record the weight and dimensions of the

ovary. Examine the outer surface for cysts, nodules, or adhesions. Bivalve the

ovary with a cut through its longest dimension and midhilum. Evaluate the

sectioned surface for any cysts or nodules, and designate their location as

either cortical, medullary, or hilar. Keep in mind that the ap-pearance of the

ovary will vary considerably with the age and the reproductive status of the

woman. The normal ovary in the reproductive years can measure up to 4 cm,

whereas an ovary this size in a postmenopausal woman warrants close evaluation.

Submit one section for every 2 cm of non-neoplastic ovary. If the ovary and

fallopian tube were removed as a prophylactic procedure in a woman with a

family history of ovarian or breast carcinoma, the entire ovary and fallopian

tube should be submitted.

Cystectomies

are usually performed for benign lesions or in women with ovarian masses who

wish to preserve their fertility. The most common indication is for the removal

of a dermoid cyst. After weighing and measuring the cyst, examine the external

surface for evidence of rupture. Place the cyst in a container, and carefully

make a small incision in the wall to allow its contents to be drained. Note the

color and consistency of the cyst fluid. Continue the incision with a pair of

scissors to expose the entire inner surface. The thick sebaceous fluid within a

dermoid cyst may have to be removed by rinsing briefly with hot water. Examine

the cyst lining, and look for any regions of granularity or papillary

projections. In dermoid cysts, look for Rokitansky’s tubercle, which appears as

a firm, nodular excrescence. This region and any other thickened areas should

be submitted in their entirety to look for evidence of immature elements.

Large, unilocular cysts with a smooth inner lining may be cut in strips and

submitted like placental membrane rolls to get a maximum view of the cyst wall.

Cystectomies for lesions other than unilocular smooth-walled cysts or dermoid

cysts should be handled as described next.

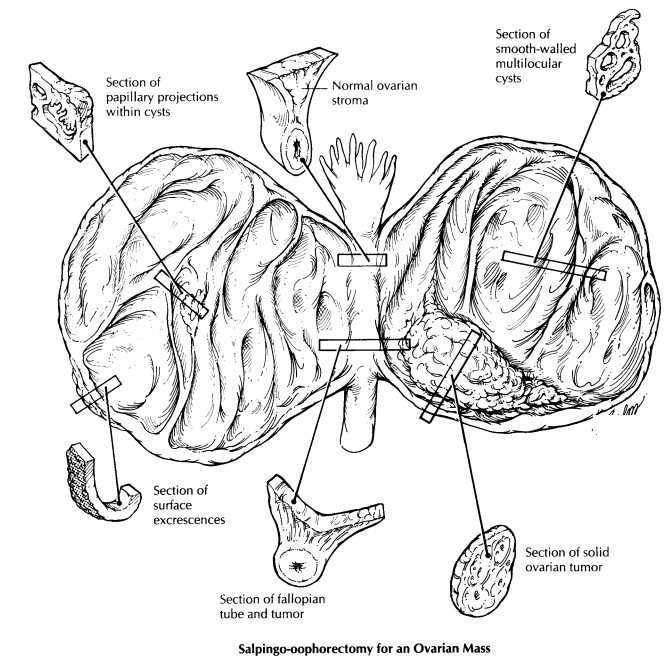

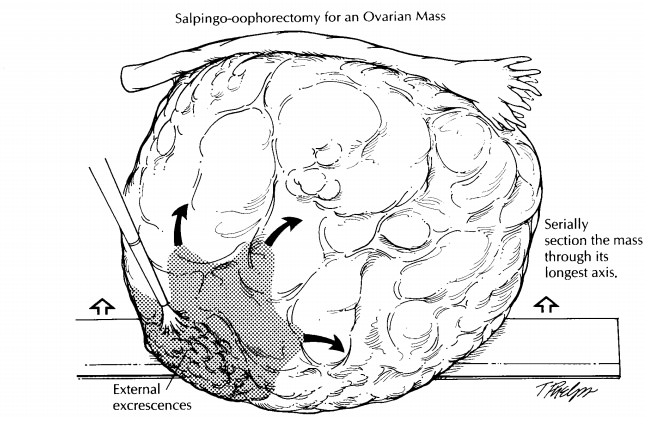

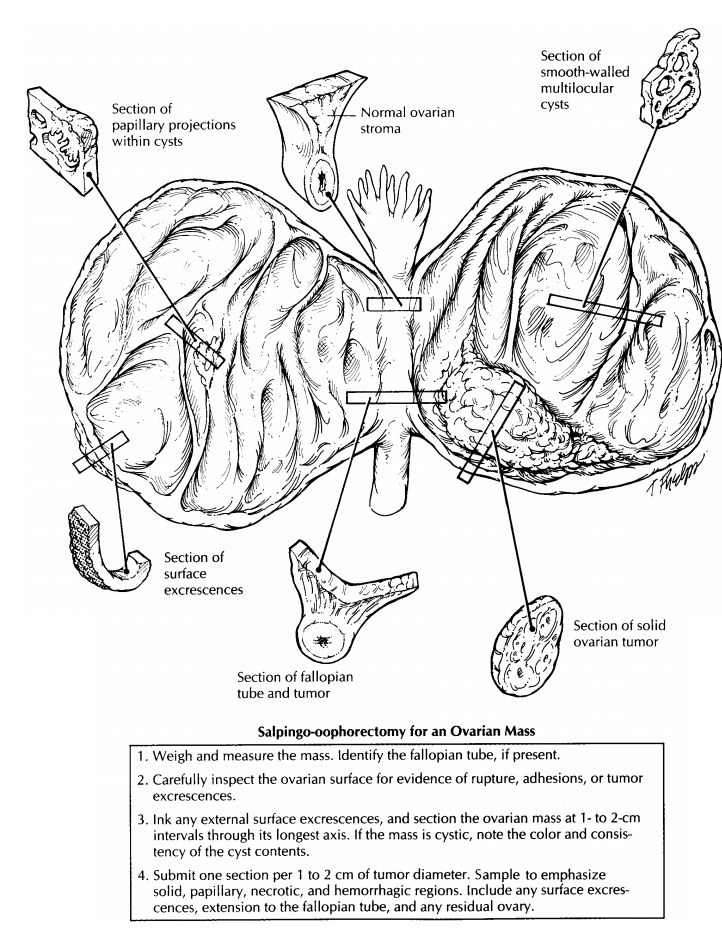

Oophorectomies

for ovarian tumors can be quite large and heavy. Often, the only recogniz-able

structure is the fallopian tube, which may be attenuated and stretched over the

ovarian sur-face. Begin by weighing and measuring the speci-men. Closely

examine the surface for evidence of rupture, adhesions, or nodular tumor excres-cences.

Ink these regions for orientation. Section the ovarian mass at 1-cm intervals

through its longest axis. If the mass is cystic, you may want to perform this

in a pan or on a work station that allows for easy drainage of fluid. Remem-ber

to document the color and consistency of the cyst fluid. Is the fluid serous,

mucinous, or hem-orrhagic? Note whether the mass is solid, cystic, or both. If

both, document the percentage of each region. Examine the surfaces of the cysts

for evi-dence of granularity, nodules, or papillary projec-tions. The thickness

of the cyst walls should also be recorded. Describe any regions of hemorrhage

or necrosis. Try to find any residual ovarian pa-renchyma. This is commonly

found in the region immediately adjacent to the fallopian tube. If a stromal or

steroid cell tumor is suspected, tis-sue should be saved frozen in case fat

stains are needed. Consider saving frozen tissue for any small, blue,

round-cell tumor, particularly if the tumor is in a pediatric patient or is predominantly

intra-abdominal. Photographs of the cut surface can aid in documentation of the

mass and for designating where sections were taken. At this point, it may be

helpful to fix the 1-cm slices in formalin before further manipulation.

Historically,

ovarian tumors are submitted with a minimum of one section per 1 to 2 cm of the

greatest tumor dimension. This rule is espe-cially useful in the case of

mucinous tumors, which tend to have only focal regions demonstrat-ing atypical

or frankly invasive elements. If the tumor is uniform throughout, as many

serous tumors are, fewer sections may be prudent. In general, sections should

be submitted from re-gions that are solid, hemorrhagic, or necrotic. Cysts that

show granular, nodular, or papillary excrescences should be thoroughly sampled.

Also be submitted in their entirety to look for evidence of immature elements.

Large, unilocular cysts with a smooth inner lining may be cut in strips and

submitted like placental membrane rolls to get a maximum view of the cyst wall.

Cystectomies for lesions other than unilocular smooth-walled cysts or dermoid

cysts should be handled as described next.

Oophorectomies

for ovarian tumors can be quite large and heavy. Often, the only recogniz-able

structure is the fallopian tube, which may be attenuated and stretched over the

ovarian sur-face. Begin by weighing and measuring the speci-men. Closely

examine the surface for evidence of rupture, adhesions, or nodular tumor

excres-cences. Ink these regions for orientation. Section the ovarian mass at

1-cm intervals through its longest axis. If the mass is cystic, you may want to

perform this in a pan or on a work station that allows for easy drainage of

fluid. Remem-ber to document the color and consistency of the cyst fluid. Is

the fluid serous, mucinous, or hem-orrhagic? Note whether the mass is solid,

cystic, or both. If both, document the percentage of each region. Examine the

surfaces of the cysts for evi-dence of granularity, nodules, or papillary

projec-tions. The thickness of the cyst walls should also be recorded. Describe

any regions of hemorrhage or necrosis. Try to find any residual ovarian

pa-renchyma. This is commonly found in the region immediately adjacent to the

fallopian tube. If a stromal or steroid cell tumor is suspected, tis-sue should

be saved frozen in case fat stains are needed. Consider saving frozen tissue

for any small, blue, round-cell tumor, particularly if the tumor is in a

pediatric patient or is predominantly intra-abdominal. Photographs of the cut

surface can aid in documentation of the mass and for designating where sections

were taken. At this point, it may be helpful to fix the 1-cm slices in formalin

before further manipulation.

Historically, ovarian tumors are submitted with a minimum of one section per 1 to 2 cm of the greatest tumor dimension. This rule is espe-cially useful in the case of mucinous tumors, which tend to have only focal regions demonstrat-ing atypical or frankly invasive elements. If the tumor is uniform throughout, as many serous tumors are, fewer sections may be prudent. In general, sections should be submitted from re-gions that are solid, hemorrhagic, or necrotic. Cysts that show granular, nodular, or papillary excrescences should be thoroughly sampled.

Also include

any regions that appear sieve-like or honeycombed. Multiple large unilocular

cysts may be more judiciously sampled. Sections that demonstrate the junction

between the ovary and adjacent fallopian tube, as well as any residual ovary,

should also be submitted.

Specimens for Ovarian Tumor Staging

The

staging procedure for an ovarian tumor can include an omentectomy, multiple

biopsies of the peritoneum, and lymph node dissections.

Omentectomy

specimens should be weighed, measured, and serially sectioned at 0.5-cm

inter-vals to look for gross tumor nodules. Measure the size of the gross tumor

and specifically indicate if it is 2 cm or less or more than 2 cm for staging

purposes. Palpate the fat for areas of induration or small miliary nodules. For

grossly visible tumor involvement, one to three representative sections should

be submitted for histology. If the tumor is not grossly visible, take multiple

sections from the firmest regions in the omental fat. Five representative

sections are usually suffi-cient, although some authorities recommend up to ten

sections.

Peritoneal

small biopsies should be routinely processed and submitted in their entirety. If

the tumor extensively involves the pelvic perito-neum, a cavitronic ultrasonic

surgical aspirator may be used to remove the implants. Tissue removed this way

can be handled like a curet-tage specimen.

A

predominant mass in the omentum or peri-toneum, with no ovarian involvement and

no tumor in the ovary invading to a depth of 5 mm or more, is generally

considered to be a primary peritoneal carcinoma.

Lymph

nodes are received separately and des-ignated by location. They can be handled

in a routine manner for evaluation of metastatic dis-ease.

Important Issues to Address in Your Surgical Pathology Report on Ovarian Tumors

· What

procedure was performed, and what structures/organs are present?

· Is a

neoplasm present? Is it of epithelial, sex-cord/stromal, germ cell, or

metastatic origin? Metastatic involvement is suggested by the presence of

multiple tumor nodules, surface implants, and vascular space involvement.

· What are

the size, histologic type, and grade of the neoplasm?

· Was the

ovarian capsule ruptured?

· Does the

tumor involve the ovarian capsule?

· Does the

tumor involve the adjacent fallopian tube or broad ligament?

· Is there

capillary–lymphatic space invasion?

· If

submitted, does the tumor involve the con-tralateral ovary and/or the serosa or

paren-chyma of the uterus? When identical tumors involve both the ovary and

endometrium, con-sider independent primary sites of origin.

· Does the

tumor involve the omentum? Is the tumor microscopic, 2 cm or less, or more than

2 cm? Consider a primary peritoneal origin if there is no or minimal ovarian

involvement.

· Does the

tumor involve any lymph nodes? In-clude the number of nodes involved and the

number of nodes examined at each specified site.

·

Do the soft tissue staging biopsies show tumor

implants? If so, specify whether they are inva-sive or noninvasive.

Related Topics