Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Somatoform Disorders

Undifferentiated Somatoform Disorder

Undifferentiated Somatoform Disorder

Definition

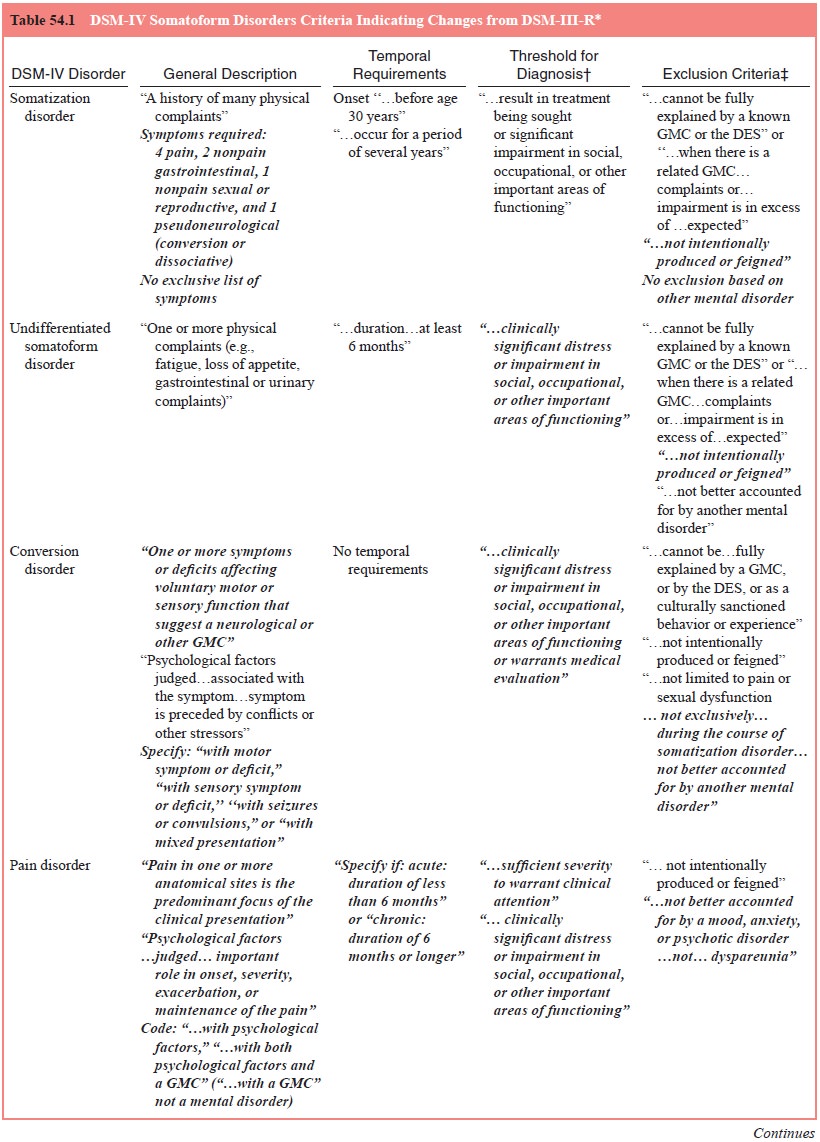

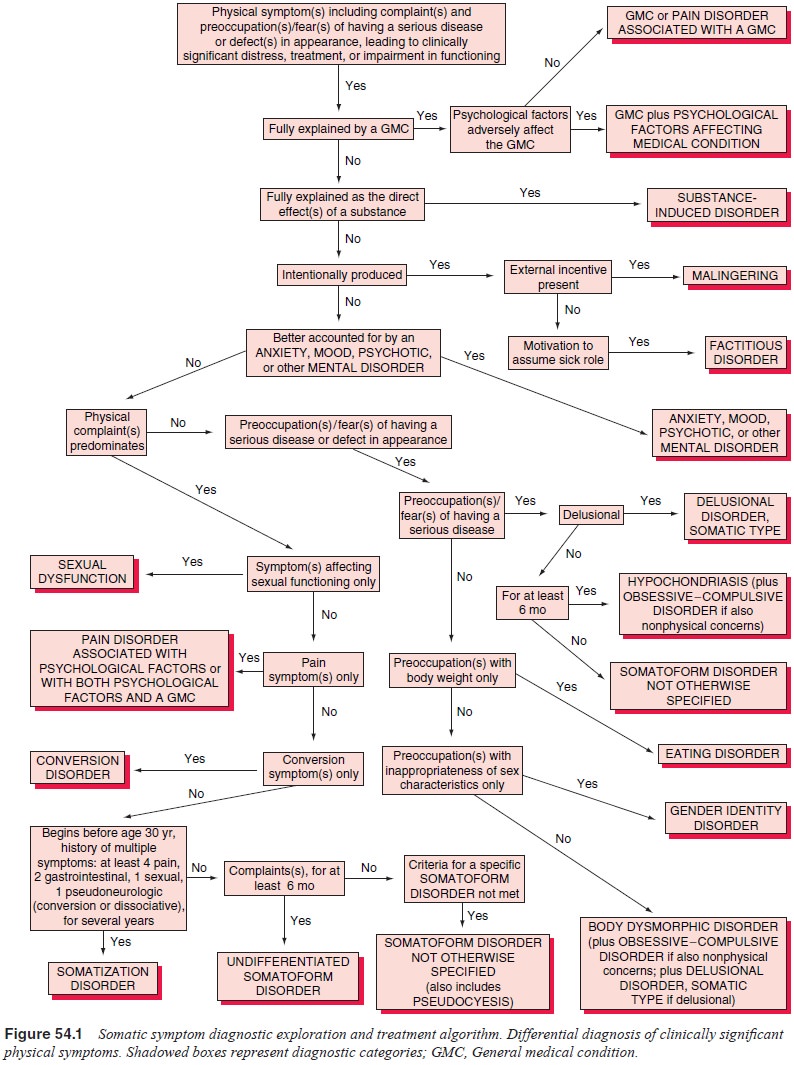

As defined in DSM-IV, this category includes disturbances of at least 6

months’ duration, with one or more unintentional, clini-cally significant,

medically unexplained physical complaints (see Table 54.1). In a sense, it is a

residual category, subsuming syn-dromes with somatic complaints that do not

meet criteria for any of the “differentiated” somatoform disorders yet are not

better accounted for by any other mental disorder. On the other hand, it is a

less residual category than somatoform disorder NOS, in that the disturbance

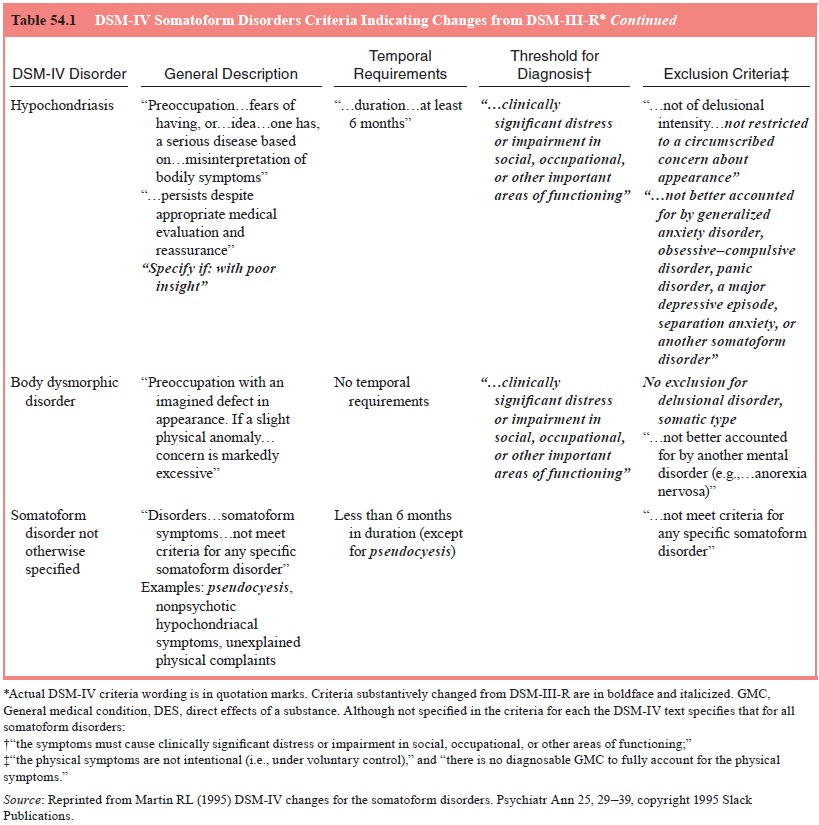

must last at least 6 months (see Figure 54.1). Vir-tually any unintentional,

medically unexplained physical symp-toms causing clinically significant

distress or impairment can be considered. In effect, this category serves to

capture syndromes that resemble somatization disorder but do not meet full

criteria.

Epidemiology

Some have argued that undifferentiated somatoform disorder is the most

common somatoform disorder. Escobar and coworkers (1991), using an abridged

somatization disorder construct requir-ing six somatic symptoms for women and

four for men, reported that 11% of nonHispanic US whites and Hispanics, 15% of

US blacks and 20% of Puerto Ricans in Puerto Rico fulfilled criteria. A

preponderance of women was evident in all groups except the Puerto Rican sample

(see Table 54.1). According to Escobar, such an abridged somatoform syndrome is

100 times more prevalent than a full somatoform syndrome

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

In comparison to when the full criteria for the well-validated

so-matization disorder are met, exclusion of an as yet undiscovered general

medical or substance-induced explanation for physical symptoms is far less

certain when the less stringent criteria for undifferentiated somatoform

disorder are met. Thus, the diagno-sis of undifferentiated somatoform disorder

should remain tenta-tive, and new symptoms should be carefully investigated.

Because undifferentiated somatoform disorder represents somewhat of a

residual category, the major diagnostic process, once occult general medical

conditions and substance-induced explanations have been considered, is one of

exclusion. As shown in Figure 54.1, whether the somatic symptoms are

intentionally produced as in malingering and factitious disorder must be

ad-dressed. Here, motivation for external rewards (for malingering) and a

pervasive intent to assume the sick role (for factitious dis-order) must be

assessed. The next consideration is whether the somatic symptoms are the

manifestation of another psychiatric disorder. Anxiety and mood disorders

commonly present with somatic symptoms; high rates of anxiety and major

depressive disorders are reported in patients with somatic complaints

at-tending family medicine clinics. Of course, undifferentiated somatoform

disorder could be diagnosed in addition to one of these disorders, so long as

the symptoms are not accounted for by the other psychiatric disorder. Crucial

in this determination is whether the symptoms are present during periods in

which the anxiety or mood disorders are not actively present.

Next, other somatoform disorders must be considered. In general,

undifferentiated somatoform disorders are characterized by unexplained somatic

complaints; the most common accord-ing to Escobar and coworkers (Escobar et al., 1989) are female reproductive

symptoms, excessive gas, abdominal pain, chest pain, joint pain, palpitations

and fainting, rather than preoccupa-tions or fears as in hypochondriasis or

body dysmorphic disor-der. However, a patient with some manifestations of these

two disorders but not meeting full criteria could conceivably receive a

diagnosis of undifferentiated somatoform disorder. An exam-ple is a patient with

recurrent yet shifting hypochondriacal con-cerns that do respond to medical

reassurance. If symptoms are restricted to those affecting the domains of

sexual dysfunction, pain, or pseudoneurological symptoms, and the specific

criteria for a sexual dysfunction, pain disorder and/or conversion disor-der

are met, the specific disorder or disorders should be diag-nosed. If other

types of symptoms or symptoms of more than one of these disorders have been

present for at least 6 months, yet criteria for somatization disorder are not

met, undifferentiated somatoform disorder should be diagnosed. By definition,

undif-ferentiated somatoform disorder requires a duration of 6 months. If this

criterion is not met, a diagnosis of somatoform disorder NOS should be considered.

Patients

with an apparent undifferentiated somatoform disorder should be carefully

evaluated for somatization disorder. Typically, patients with somatization

disorder are inconsistent his-torians, at one evaluation reporting a large

number of symptoms fulfilling criteria for the full syndrome, at another time

endorsing fewer symptoms. In addition, with follow-up, additional symp-toms may

become evident, and criteria for somatization disorder will be satisfied.

Patients with multiple somatic complaints not diagnosed with somatization

disorder because of a reported onset later than 30 years of age may be

inaccurately reporting a later age at onset. If the late age at onset is

accurate, the patient should be carefully scrutinized for an occult general

medical disorder.

In addition to the range of symptoms specified in the other somatoform

disorders, patients complaining primarily of fatigue (chronic fatigue

syndrome), bowel problems (irritable bowel syn-drome), or multiple muscle

aches/weakness (fibromylagia) can be considered for undifferentiated somatoform

disorder. Substantial controversy exists regarding the etiology of such

syndromes. Even if an explanation on the basis of a known pathophysiological

mechanism cannot be established, many argue that the syndromes should be

considered general medical conditions. However, for the time being, these

syndromes could be considered in a highly tentative manner under the

undifferentiated somatoform disorder rubric. Careful reconsideration of the

psychiatric label should be undertaken at regular intervals if the symptoms

persist. The psy-chiatrist should remain ever vigilant to the emergence of

another general medical or psychiatric condition. When patients are di-agnosed

with chronic fatigue syndrome, careful evaluation pro-cedures are recommended.

Course, Natural History and Prognosis

As shown in Table 54.1, it appears that the course and prognosis of

undifferentiated somatoform disorder are highly variable. This is not

surprising, because the definition of this disorder allows a great deal of

heterogeneity.

Treatment

In view of the broad inclusion and minimal exclusion criteria for

undifferentiated somatoform disorder, it is difficult to make treat-ment

recommendations beyond the generic guidelines outlined for the somatoform

disorders in general. More definitive recom-mendations await a more extensive

empirical database. A sub-stantial proportion of patients with undifferentiated

somatoform disorders improve or recover with no formal therapy. However,

appropriate psychotherapy and pharmacological intervention may accelerate the

process.

Some recommendations for patients with symptoms of headache,

fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndrome, condi-tions that some would include

under undifferentiated somatoform disorder. Generally recommended are brief

psychotherapy of a supportive and educative nature. As with somatization

disorder, the physician–patient relationship is of great importance. Judi-cious

use of pharmacotherapy may also be of benefit, particularly if the somatoform

syndrome is intertwined with an anxiety or depressive syndrome. Here, usual

antianxiety and antidepressant medications are recommended. Patients with

unexplained pains may benefit from pain management strategies as outlined in

the pain disorder section.

Related Topics