Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Somatoform Disorders

Hypochondriasis

Hypochondriasis

Definition

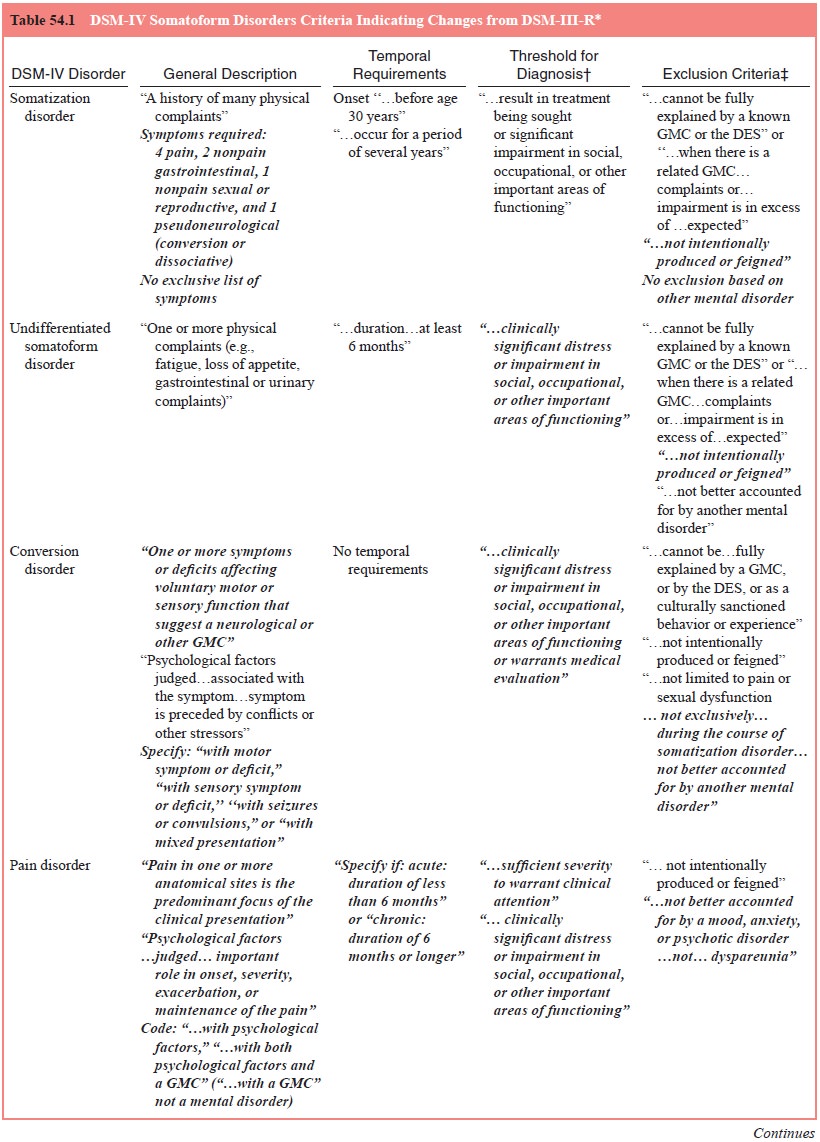

The essential feature in hypochondriasis is preoccupation with fears or

the idea of having a serious disease based on the “mis-interpretation of bodily

symptoms”. (see Table 54.1). This is in contrast to somatization disorder,

conversion disorder and pain disorder, in which the symptoms themselves are the

predominant focus. There was some debate in the development of DSM-IV as to

whether it was necessary that a body complaint be present. On the basis of

empirical data, however, it was determined that this requirement was a valid

one and helped to distinguish the “disease conviction” of hypochondriasis from

“disease fear” as in phobic disorder. Bodily symptoms may be interpreted

broadly to include misinterpretation of normal body functions. In hypo-chondriasis,

the preoccupation persists despite reassurance from physicians and the

accumulation of evidence to the contrary. As in the other somatoform disorders,

symptoms must result in clinically significant distress or impairment in

important areas of functioning. The duration must be at least 6 months.

Hypochon-driasis is not diagnosed if the hypochondriacal concerns are bet-ter

accounted for by another psychiatric disorder, such as major depressive

episodes or various psychotic disorders with somatic delusions.

Throughout the modern period, there has been contro-versy as to whether

hypochondriasis represented an independent, discrete disease entity. Some

maintain that hypochondriasis is virtually always secondary to another

psychiatric disorder, usu-ally depression. A number of studies suggested that

of the many patients with hypochondriacal complaints, few meet criteria for the

full diagnosis. Moreover, the lack of bimodality to the com-plaints suggests a

continuum rather than a discrete entity.

In the development of DSM-IV, owing to observations that the disease

conviction resembled disease phobia or the incorrigi-ble ideas of

obsessive–compulsive disorder, placement of hypo-chondriasis with the anxiety

disorders was considered. Similarly, a case can be made that disease conviction

is on a continuum with somatic delusions of disease, suggesting inclusion with

the delu-sional disorders. In the end, such considerations were resolved by

keeping hypochondriasis with the somatoform disorders, de-fining it in terms of

an idea that one already has a particular ill-ness rather than fears of

acquiring one to distinguish it from a disease phobia, and by excluding cases

in which the idea was of delusional proportions to differentiate

hypochondriasis from delusional disorder, somatic type.

Epidemiology

Some degree of preoccupation with disease is apparently com-mon. As

reviewed by Kellner (1991), 10 to 20% of “normal” and 45% of “neurotic” persons

have intermittent unfounded worries about illness, with 9% of patients doubting

reassurances given by physicians. Kellner also estimated that 50% of all

patients attend-ing physicians’ offices “suffer either primary hypochondriacal

symptoms or have minor somatic disorders with hypochondriacal

overlay”. How these relate to hypochondriasis as a disorder is difficult to

assess because these estimates do not appear to dis-tinguish between a focus on

the symptoms themselves (as in somatization disorder) and preoccupation with

the implications of the symptoms (as in hypochondriasis). The Epidemiological

Catchment Area study (Robins et al., 1984) did not consider hy-pochondriasis. A 1965

study reported prevalence figures ranging from 3 to 13% in different cultures,

but it is not clear whether this represents a syndrome comparable to the current

definition or just hypochondriacal symptoms. As already noted, many pa-tients

manifest some hypochondriacal symptoms as part of other psychiatric disorders,

and others have transient hypochondriacal symptoms in response to stresses such

as serious physical illness yet never fulfill the inclusion criteria for DSM-IV

hypochondria-sis. Assessment of the incidence and prevalence of

hypochondria-sis undoubtedly requires study of general or primary care rather

than psychiatric populations, because patients with hypochon-driasis are

convinced that they suffer from some physical illness. To date, study of such

populations suggests that 4 to 9% of pa-tients in general medical settings

suffer from hypochondriasis.

It does appear that hypochondriasis is equally common in males and

females.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Until recently, psychoanalytic hypotheses of etiology predomi-nated.

Freud hypothesized that hypochondriasis represented “the return of object

libido onto the ego with cathexis of the body” (Viederman, 1985). Subsequently,

the cathexis to the body hy-pothesis was elaborated on to include

interpretations involving disturbed object relations – displacement of

repressed hostility to the body to communicate anger indirectly to others.

Dynamic mechanisms involving masochism, guilt, conflicted dependency needs and

a need to suffer and be loved at the same time have also been suggested

(Stoudemire, 1988). The presence of such “narcissistic” mechanisms has been

suggested as the reason that patients with hypochondriasis were “unanalyzable”.

Other psy-chological theories involve defense against feelings of low

self-esteem and inadequacy, perceptual and cognitive abnormalities, and operant

conditioning involving reinforcement for assump-tion of the sick role.

Biological theories have been suggested as well. Hypo-chondriacal ideas

have been attributed to a hypervigilance to insult, including overperception of

physical problems. This has been posited in particular in reference to

hypochondriasis as an aspect of depression or anxiety disorders.

Hypochondriasis has been included by some in the posited obsessive–compulsive

spectrum disorders along with obsessive–compulsive and body dysmorphic

disorders, anorexia nervosa, Tourette’s disorder, tri-chotillomania, pathological

gambling and other impulsive disor-ders. All these disorders involve repetitive

thoughts or behaviors that patients are unable to delay or inhibit without

great difficulty. Evidence for this clustering includes observations of

clinical im-provement with SSRIs such as fluoxetine even in nondepressed

patients with hypochondriasis, body dysmorphic disorder, obses-sive–compulsive

disorder and anorexia nervosa. Because such a response is not evident with

nonSSRI antidepressants, some type of common serotonin dysregulation is

suggested for these disorders.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

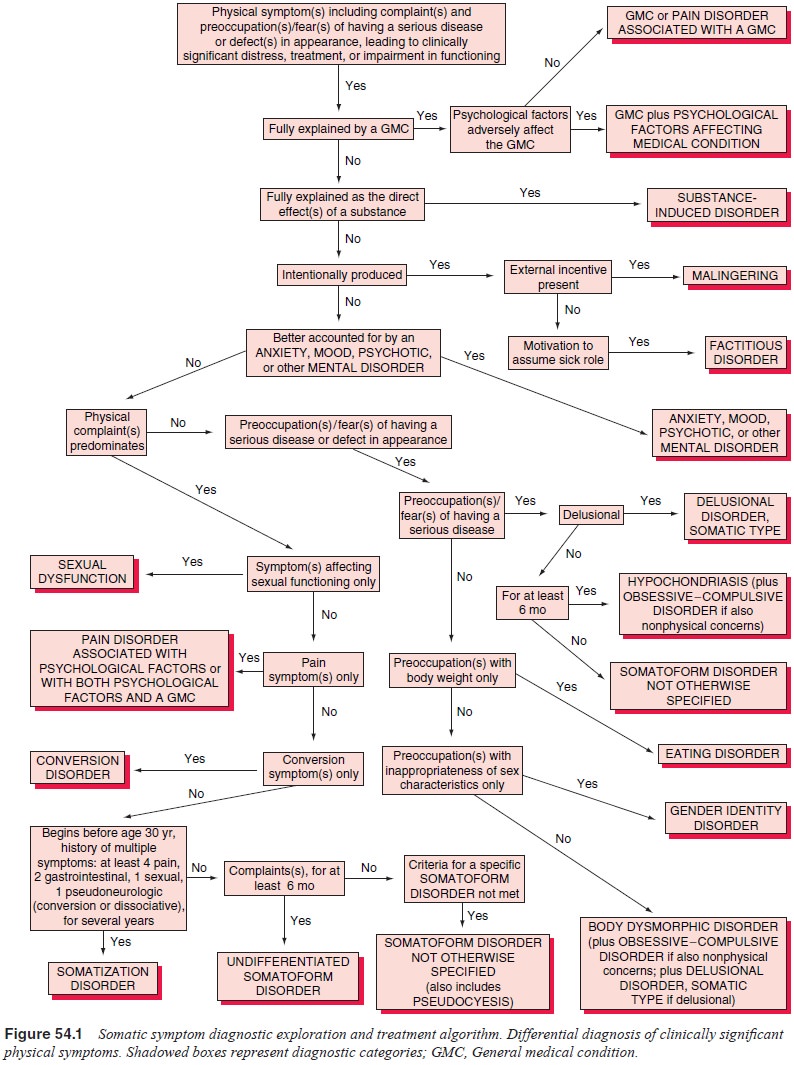

As shown in Figure 54.1, the first step in approaching patients with

distressing or impairing preoccupation with or fears of having a serious

disease is to exclude the possibility of explanation on the basis of a general

medical condition. Fears that may seem excessive may also occur in patients

with general medical conditions with vague and subjective symptoms early in

their disease course. These include neurological diseases, such as myasthenia

gravis and multiple scle-rosis; endocrine diseases; systemic diseases that

affect several organ systems, such as systemic lupus erythematosus; and occult

malignant neoplasms. The disease conviction of hypochondriasis may actually be

less amenable to medical reassurance than the fears of patients, with general

medical illnesses, who may at least temporally accept such encouragement.

Hypochondriacal complaints are not often in-tentionally produced such that

differentiation from malingering and factitious disorder is seldom a problem.

Exclusion is made if the preoccupation is better accounted for by

another psychiatric disorder. DSM-IV lists generalized anxiety disorder,

obsessive–compulsive disorder, panic disorder, a major depressive episode,

separation anxiety, or another so-matoform disorder as candidates. Chronology

will be of utmost importance in such discriminations. Hypochondriacal concerns

occurring exclusively during episodes of another disturbance, such as an

anxiety or depressive disorder, do not warrant an ad-ditional diagnosis of

hypochondriasis. The presence of other psy-chiatric symptoms will also be

helpful. For example, a patient with hypochondriacal complaints as part of a

major depressive episode will show other symptoms of depression, such as sleep

and appetite disturbance, feelings of worthlessness and self-reproach, although

depressed elderly patients may deny sadness or other expressions of depressed

mood. A confounding factor is that patients with hypochondriasis often have

comorbid anxiety or depressive syndromes. Again, characterizing the symptoms by

chronology will be useful. Treatment trials may also have diag-nostic

significance. Depressed patients who are hypochondriacal may respond to nonSSRI

antidepressant medications or elec-troconvulsive therapy (often necessary to

reverse a depressive state of sufficient severity to lead to such profound

symptoms), with resolution of the hypochondriacal as well as the depressive

symptoms.

Hypochondriasis is differentiated from other somatoform disorders such

as pain, conversion and somatization disorders by its predominant feature of

preoccupation with and fears of having an underlying illness based on the

misinterpretation of body symptoms, rather than the physical symptoms

themselves. Patients with these other somatoform disorders at times are

con-cerned with the possibility of underlying illness, but this will gen-erally

be overshadowed by a focus on the symptoms themselves.

The next consideration is whether the belief is of delu-sional

proportions. Patients with hypochondriasis, although preoccupied, generally

acknowledge the possibility that their concerns are unfounded. Delusional

patients do not. Somatic de-lusions of serious illness are seen in some cases

of schizophrenia and in delusional disorder, somatic type. In general, patients

with schizophrenia that have such delusions also show other signs of

schizophrenia, such as disorganized speech, peculiarities of thought and

behavior, hallucinations and other delusions. Belief that an underlying illness

is being caused by some bizarre proc-ess may also be seen (e.g., “I’m trying

not to defecate because it will cause my brain to turn to jelly”).

Schizophrenic patients may also show improvement with neuroleptic treatment, at

least in the “active” symptoms of their illness, under which somatic delusions

are included.

Differentiation

from delusional disorder, somatic type, may be more difficult. It is often a

thin line between preoccupation and fear that is a conviction

and that which is a delusion. Often, the distinction is made on the basis of

whether the patient can consider the possibility that the conviction is

erroneous. Yet, patients with hypochondriasis vary in the extent to which they

can do this. DSM-IV acknowledges this by its inclusion of the specifier with

poor insight. In the past, some argued that differ-entiation could be made on

the basis of response to neuroleptics, especially pimozide; patients with

delusional disorder, but not hypochondriasis, respond.

If it is concluded that the preoccupations are not delusional, the next

consideration is whether the duration requirement of 6 months has been met (see

Figure 54.1). Syndromes of less than 6 months’ duration are diagnosed under

either somatoform dis-order NOS or adjustment disorder if the symptoms are an

abnor-mal response to a stressful life event. The reason to make such a

distinction is to distinguish hypochondriasis from transient syn-dromes, the

longitudinal course of which have been shown to be more variable, suggesting

heterogeneity.

Other diagnostic considerations include whether the pre-occupations or

fears are restricted to preoccupations with being overweight, as in anorexia

nervosa; with the inappropriateness of one’s sex characteristics, as in a

gender identity disorder; or with defects in appearance, as in body dysmorphic

disorder. The pre-occupations of hypochondriasis resemble the obsessions, and

the health checking and efforts to obtain reassurance resemble the compulsions

of obsessive–compulsive disorder. However, if such manifestations are health

centered only, obsessive–compulsive disorder is not diagnosed. If, on the other

hand, nonhealth related obsessions and compulsions are present, obsessive–compulsive

disorder may be diagnosed in addition to hypochondriasis.

Course, Natural History and Prognosis

Data are conflicting, but it appears that the most common age at onset

is in early adulthood. Available data suggest that approxi-mately 25% of patients

with a diagnosis of hypochondriasis do poorly, 65% show a chronic but

fluctuating course and 10% re-cover. This pertains to the full syndrome. A much

more variable course is seen in patients with just some hypochondriacal

con-cerns. It appears that acute onset, absence of a personality disor-der and

absence of secondary gain are favorable prognostically.

Treatment

Until recently, it appeared that patients with hypochondriasis as a

primary condition benefited, but only modestly, from psychiatric intervention.

Patients referred early for psychiatric evaluation and treatment showed a

slightly better prognosis than those continu-ing with only medical evaluations

and treatments. Of course, the first step in treatment is getting the patient

to a psychiatrist. Pa-tients with hypochondriasis generally present initially

to nonpsy-chiatric physicians and are often reluctant to see a psychiatrist.

Referral should be done sensitively, with the referring physician stressing to

the patient that his or her distress is real and that psy-chiatric evaluation

will be a supplement to, not a replacement for, continued medical care.

Initially, the generic techniques outlined for the somato-form disorders

in general should be followed. However, it has not been demonstrated that a

specific psychotherapy for hypo-chondriasis is available. Dynamic psychotherapy

is of minimal effectiveness; supportive–educative psychotherapy is only

some-what helpful, and primarily for those with syndromes of less than 3 years’

duration; and cognitive–behavioral therapy, especially response prevention of

checking rituals and reassurance seeking, is of only moderate effectiveness at

best. All of these techniques seem to lack definitive effects on

hypochondriasis itself.

Until recently, this could also be said of pharmacological approaches.

Pharmacotherapy of comorbid depressive or anxiety syndromes was often

effective, and control of such syndromes aided in general management, yet

hypochondriasis itself was not ameliorated. Although controlled trials are

lacking, anecdotal and open-label studies suggest that serotoninergic agents

such as clomipramine and the SSRI fluoxetine may be effective in amel-iorating

hypochondriasis. Similar effects are expected from the other SSRIs. Response to

fluoxetine has been reported with doses recommended for obsessive–compulsive

disorder, rather than usual antidepressant doses (i.e., 60–80 mg rather than

20–40 mg/ day). Such pharmacotherapy is best combined with the generic

psychotherapy recommendations for somatoform disorders, as well as with

cognitive–behavioral techniques to disrupt the coun-terproductive checking and

reassurance-seeking behaviors.

Related Topics