Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Somatoform Disorders

Conversion Disorder

Conversion Disorder

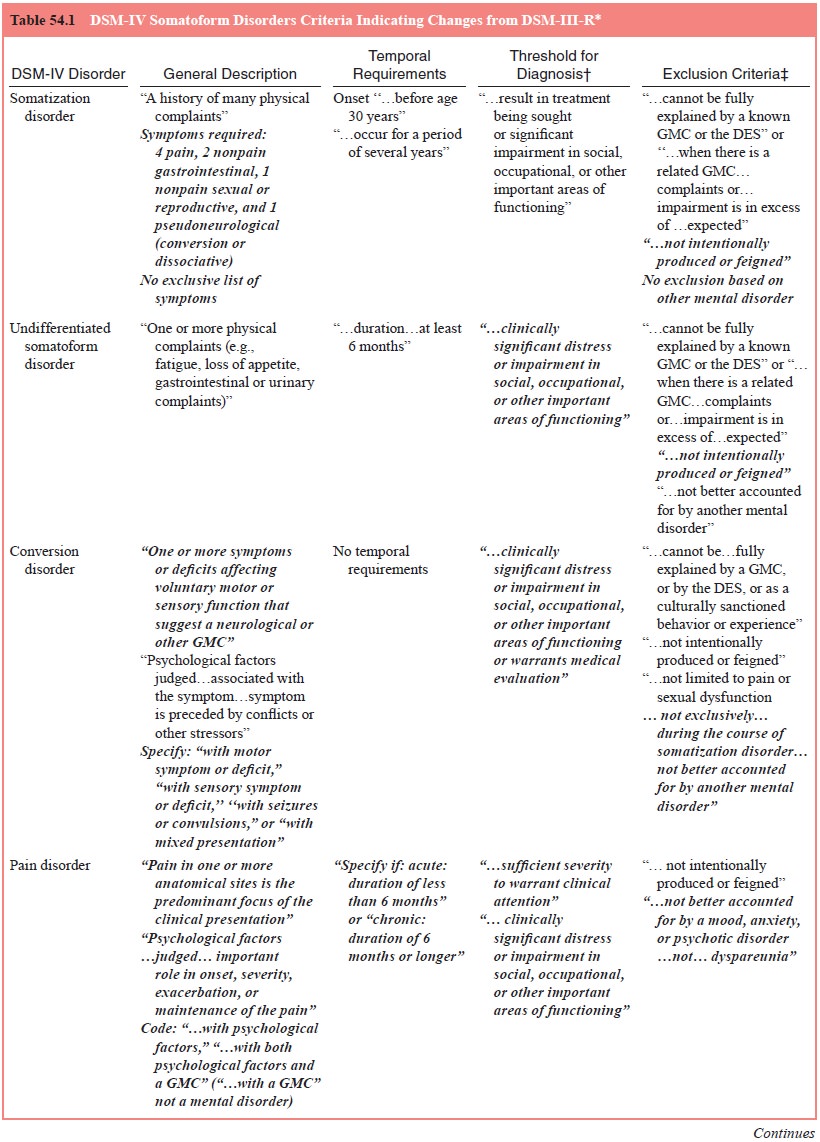

Definition

As defined in DSM-IV, conversion disorders are characterized by symptoms

or deficits affecting voluntary motor or sensory func-tion that suggest yet are

not fully explained by a neurological or other general medical condition or the

direct effects of a substance (see Table 54.1). The diagnosis is not made if

the presentation is explained as a culturally sanctioned behavior or

experience, such as bizarre behaviors resembling a seizure during a religious

cer-emony. Symptoms are not intentionally produced or feigned, that is, the

person does not consciously contrive a symptom for exter-nal rewards, as in

malingering, or for the intrapsychic rewards of assuming the sick role, as in

factitious disorder.

Four subtypes with specific examples of symptoms are de-fined: with

motor symptom or deficit (e.g., impaired coordination or balance, paralysis or

localized weakness, difficulty swallow-ing or lump in throat, aphonia and

urinary retention); with sen-sory symptom or deficit (e.g., loss of touch or

pain sensation, dou-ble vision, blindness, deafness and hallucinations); with

seizures or convulsions; and with mixed presentation (i.e., has symptoms of

more than one of the other subtypes). The list of examples is also contained

among the pseudoneurological symptoms listed in the diagnostic criteria for

somatization disorder. Although deter-mination is highly subjective and of

questionable reliability and validity, association with psychological factors

is required.

Whereas conversion symptoms are among the most dra-matic symptoms,

somatization disorder is characterized by mul-tiple unexplained symptoms in

many organ systems; in conver-sion disorder, even a single symptom affecting

voluntary motor or sensory function may suffice. Such nosological

inconsisten-cies have resulted in a great deal of confusion, both in research

and in clinical practice.

The relationship of conversion disorder to the dissociative disorders

warrants comment. Long recognized as related, they were subsumed as subtypes of

hysterical neurosis in DSM-II: conversion involving voluntary motor and sensory

functioning, and dissociation affecting memory and identity. DSM-IV-TR text

acknowledges the symptomatic, epidemiological and prob-able pathogenetic

similarities between conversion and dissocia-tive symptoms. Such symptoms have

been attributed to similar psychological mechanisms, and they often occur in

the same in-dividual, sometimes during the same episode of illness. DSM-IV-TR

does suggest that patients with conversion disorder be care-fully scrutinized

for dissociative symptoms.

Hallucinations are included among the sensory nervous symptoms in

DSM-IV. The concept of conversion hallucinations has a long tradition and its

inclusion as a conversion symptom was supported by the somatization disorder

field trial, in which one-third of a large sample of nonpsychotic women with

evi-dence of unexplained somatic complaints reported a history of

hallucinations. Among the 40% who had symptoms that met criteria for

somatization disorder, more than half reported hal-lucinations. Women with

other conversion symptoms were more likely to report hallucinations than were

those with no other conversion symptoms.

In general, conversion hallucinations (referred to by some as

pseudohallucinations) differ in several ways from those in psy-chotic

conditions. Conversion hallucinations typically occur in the absence of other

psychotic symptoms, insight that the halluci-nations are not real may be

retained, and they often involve more than one sensory modality, whereas

hallucinations in psychoses generally involve a single sensory modality,

usually auditory. Conversion hallucinations also often have a naive, fantastic,

or childish content, as if they are part of a fairy tale, and are de-scribed

eagerly, sometimes even provocatively, as an interesting story (e.g., “I was

driving downtown and a flying saucer flew over my car and I saw you [the

psychiatrist] in a window and I heard your voice calling to me”). They often

bear some understandable psychological purpose, although the patient may not be

aware of intent. In the example given, the “sighting” was reported at the time

that no further sessions were scheduled.

Epidemiology

Vastly different estimates of the incidence and prevalence of conversion

disorder have been reported. Much of this differencemay be attributable to

methodological differences from study to study, including the changing

definition of conversion disorder, ascertainment procedures and populations

studied. General pop-ulation estimates have generally been derived indirectly,

extrapo-lating from clinic or hospital samples.

Conversion symptoms themselves may be common; it was reported that 25%

of normal postpartum and medically ill women had a history of conversion

symptoms at some time dur-ing their life (Cloninger, 1993), yet in some

instances, there may have been no resulting clinically significant distress or

impair-ment. Lifetime prevalence rates of treated conversion symptoms in

general populations are much more modest, ranging from 11 to 500 per 100 000

(see Table 54.1). About 5 to 24% of psychiatric outpatients, 5 to 14% of

general hospital patients and 1 to 3% of outpatient psychiatric referrals reported

a history of conversion symptoms, although their current treatment was not

necessar-ily for conversion symptoms. A rate of nearly 4% of outpatient

neurological referrals and 1% of neurological admissions (Ziegler and Paul,

1954) involved conversion disorder. In virtually all studies, an excess (to the

extent of 2:1 to 10:1) of women reported conversion symptoms relative to men.

In part, this may relate to the simple fact that women seek medical evaluation

more often than men do, but it is unlikely that this fully accounts for the sex

difference. There is a predilection for lower socioeconomic status; less

educated, less psychologically sophisticated and ru-ral populations are

overrepresented. Consistent with this, higher rates (nearly 10%) of outpatient psychiatric

referrals are for con-version symptoms in “developing” countries. As countries

de-velop, there may be a declining incidence in time, which may relate to

increasing levels of education, and medical and psycho-logical sophistication.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The term conversion implies etiology because it is derived from hypothesized

mechanism of converting psychological conflicts into somatic symptoms, often

symbolically (e.g., repressed rage is converted into paralysis of an arm that

could be used to strike). A number of psychological factors have been promoted

as part of such an etiological process, but evidence for their essential

involvement is scanty at best. Theoretically, anxiety is reduced by keeping an

internal conflict or need out of awareness by sym-bolic expression of an

unconscious wish as a conversion symp-tom (primary gain). However, individuals

with active conversion symptoms often continue to show marked anxiety,

especially on psychological tests. Symbolism is infrequently evident, and its

evaluation involves highly inferential and unreliable judgments.

Overinterpretation of symbolism in persons with occult medi-cal disorder may

contribute to misdiagnosis. Secondary gain, whereby conversion symptoms allow

avoidance of noxious ac-tivities or the procurement of otherwise unavailable

support, may also occur in persons with medical conditions, who may take

advantage of such benefits.

Individuals with conversion disorder may show a lack of concern out of

keeping with the nature or implications of the symptom (the so-called la belle indifférence). However,

indifference to symptoms is not invariably present in conversion disorder and

is also seen in individuals with general medical con-ditions, on the basis of

denial or stoicism. Conversion symptoms may present in a dramatic or histrionic

fashion and may be highly suggestible. A dramatic presentation is also seen in

distressed individuals with medical conditions. Even symptoms based on an

underlying medical condition may respond to suggestion, at leasttemporarily. In

many instances, preexisting personality disorders (in particular histrionic

personality disorder) are evident and may predispose to conversion disorder.

Persons with conversion dis-order may often have a history of disturbed

sexuality many (one-third) report a history of sexual abuse, especially

incestuous.

If not directly etiological, many psychosocial factors have been

suggested as predisposing to conversion disorder. At a minimum, many persons

with conversion disorder are in cha-otic domestic and occupational situations.

As previously men-tioned, individuals from rural backgrounds and those who are

psychologically and medically unsophisticated appear to be pre-disposed, as are

those with existing neurological disorders. In the last case, a tendency to

conversion symptoms has been attrib-uted to “modeling”, that is, patients with

neurological disorders are likely to have observed in others, as well as in

themselves, various neurological symptoms, which they then may simulate as

conversion symptoms.

Available data suggest a genetic contribution. Conver-sion symptoms are

more frequent in relatives of individuals with conversion disorder. In a

nonblinded study, rates of conversion disorder were found to be elevated

tenfold in female (fivefold in male) relatives of patients with conversion

disorder. Nongenetic familial factors, particularly incestuous childhood sexual

abuse, may also be involved in some. Nearly one-third of individuals with

medically unexplained seizures reported childhood sex-ual abuse, compared with

less than 10% of those with complex partial epilepsy.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

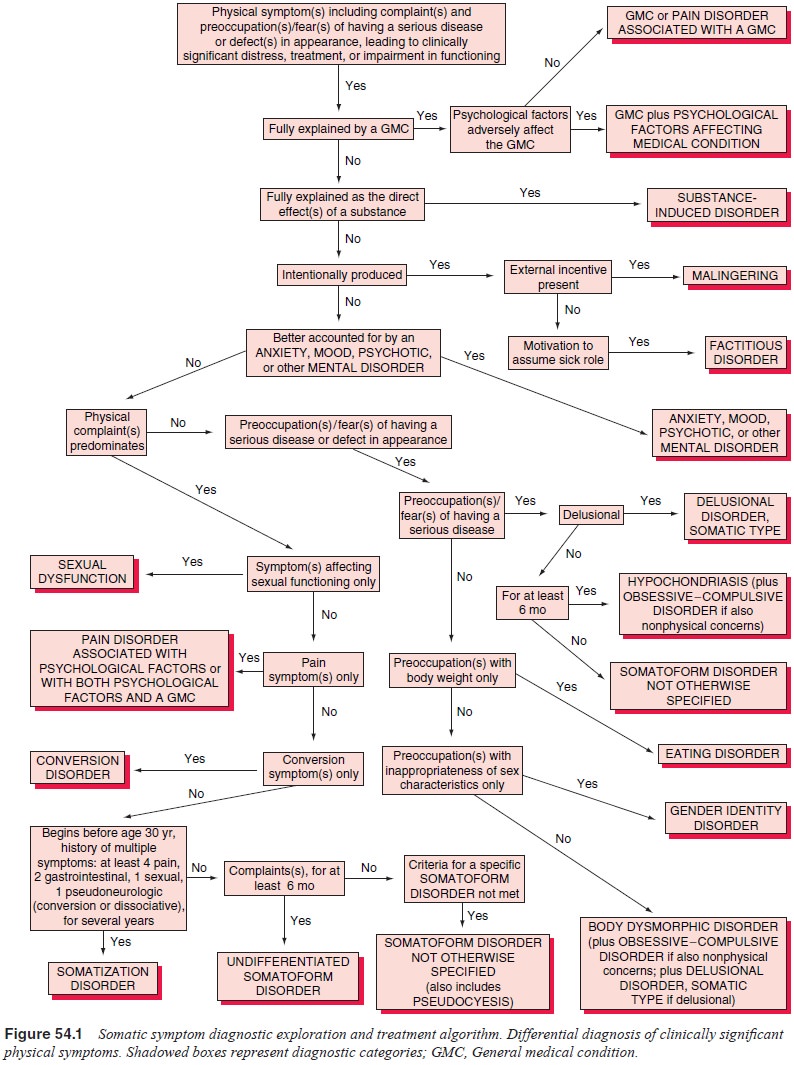

As shown in Figure 54.1, the first consideration is whether the

conversion symptoms are explained on the basis of a general medical condition.

Because conversion symptoms by definition affect voluntary motor or sensory

function (thus pseudoneuro-logical), neurological conditions are usually

suggested, but other general medical conditions may be implicated as well.

Neurolo-gists are generally first consulted by primary care physicians for

conversion symptoms; psychiatrists become involved only after neurological or

general medical conditions have been reasonably excluded. Nonetheless,

psychiatrists should have a good appre-ciation of the process of making such

exclusions. More than 13% of actual neurological cases are diagnosed as

functional before the elucidation of a neurological illness (Perkin, 1989).

Even after referral, vigilance for an emerging general medical condi-tion should

continue. A significant percentage – 21 to 50% – of patients diagnosed with

conversion symptoms are found to have neurological illness on follow-up.

Apparent

conversion symptoms mandate a thorough eval-uation for possible underlying

physical explanation. This evalua-tion must include a thorough medical history;

physical (especially neurological) examination; and radiographical, blood,

urine and other tests as clinically indicated. Reliance should not be placed on

determination of whether psychological factors explain the symptom. Such

determinations are unreliable except, perhaps, in cases in which there is a

clear and immediate temporal rela-tionship between a psychosocial stressor and

the symptom, or in cases in which similar situations led to conversion symptoms

in the past. A history of previous conversion or other unexplained symptoms,

particularly if somatization disorder is diagnosable, lessens the probability

that an occult medical condition will be identified. Although conversion

symptoms may occur at any age, symptoms are most often first manifested in late

adolescence or early adulthood. Conversion symptoms first occurring in middle age or later should increase suspicion of an occult physical illness.

Symptoms of many neurological illnesses may appear in-consistent with

known neurophysiological or neuropathological processes, suggesting conversion

and posing diagnostic prob-lems. These illnesses include multiple sclerosis, in

which blind-ness due to optic neuritis may initially present with normal fundi;

myasthenia gravis, periodic paralysis, myoglobinuric myopathy, polymyositis and

other acquired myopathies, in which marked weakness in the presence of normal

deep tendon reflexes may occur; and Guillain–Barré syndrome, in which early

extremity weakness may be inconsistent.

Complicating diagnosis is the fact that physical illness and conversion

or other apparent psychiatric overlay are not mutually exclusive. Patients with

physical illnesses that are incapacitating and frightening may appear to be

exaggerating symptoms. Also, patients with actual neurological illness will

also have “pseudo” symptoms. For example, patients with actual seizures may

have pseudoseizures as well. Considering these observations, psychia-trists

should avoid a rash and hasty diagnosis of conversion disor-der when faced with

symptoms that are difficult to interpret.

As with the other somatoform disorders, symptoms of conversion disorder

are not intentionally produced, in distinc-tion to malingering or factitious

disorder. To a large part, this determination is based on assessment of the

motivation for exter-nal rewards (as in malingering) or for the assumption of

the sick role (as in factitious disorder). The setting is often an important

consideration. For example, conversion-like symptoms are fre-quent in military

or forensic settings, in which obvious potential rewards make malingering a

serious consideration.

A diagnosis of conversion disorder should not be made if a conversion

symptom is fully accounted for by a mood disorder or by schizophrenia (e.g.,

disordered motility as part of a cata-tonic syndrome of a psychotic mood

disorder or schizophrenia). If the symptom is a hallucination, it must be

remembered that the descriptors differentiating conversion from psychotic

hallu-cinations should be seen only as rules of thumb. Differentiation should

be based on a comprehensive assessment of the illness. In the case of

hallucinations, post traumatic stress disorder and dis-sociative identity

disorder (multiple personality disorder) must also be excluded. If the

conversion symptom cannot be fully ac-counted for by the other psychiatric

illness, conversion disorder should be diagnosed in addition to the other

disorder if it meets criteria (e.g., an episode of unexplained blindness in a

patient with a major depressive episode). In hypochondriasis, neurologi-cal

illness may be feared (“I have strange feelings in my head; it must be a brain

tumor”), but the focus here is on preoccupation with fear of having the illness

rather than on the symptom itself as in conversion disorder.

By definition, if symptoms are limited to sexual dysfunc-tion or pain,

conversion disorder is not diagnosed. Criteria for so-matization disorder

require multiple symptoms in multiple organ systems and functions, including

symptoms affecting motor or sensory function (conversion symptoms) or memory or

identity (dissociative symptoms). Thus, it would be superfluous to make an

additional diagnosis of conversion disorder in the context of a somatization

disorder.

A last consideration is whether the symptom is a culturally sanctioned

behavior or experience. Conversion disorder should not be diagnosed if symptoms

are clearly sanctioned or even ex-pected, are appropriate to the sociocultural

context, and are not associated with distress or impairment. Seizure-like

episodes, such as those that occur in conjunction with certain religious

ceremonies, and culturally expected responses, such as women “swooning” in

response to excitement in Victorian times, qualify as examples of these

symptoms.

Course, Natural History and Prognosis

Age at onset is typically from late childhood to early adulthood. Onset

is rare before the age of 10 years and after 35 years, but cases with an onset

as late as the ninth decade have been reported. The likelihood of a

neurological or other medical condition is increased when the age at onset is

in middle or late life. Develop-ment is generally acute, but symptoms may

develop gradually as well. The course of individual conversion symptoms is

generally short; half to nearly all symptoms remit by the time of hospital

discharge. However, symptoms relapse within 1 year in one-fifth to one-fourth

of patients. Typically, one symptom is present in a single episode, but

multiple symptoms are generally involved longitudinally. Factors associated

with good prognosis include acute onset, clearly identifiable precipitants, a

short interval be-tween onset and institution of treatment, and good

intelligence. Conversion blindness, aphonia and paralysis are associated with

relatively good prognosis, whereas patients with seizures and tremor do more

poorly. Some patients diagnosed initially with conversion disorder will have a

presentation that meets criteria for somatization disorder when they are

observed longitudinally.

Individual conversion symptoms are generally self-limited and do not

lead to physical changes or disabilities. Rarely, physi-cal sequelae such as

atrophy may occur. Marital and occupational problems are not as frequent in

patients with conversion disorder as they are in those with somatization

disorder.

Treatment

Reports of the treatment of conversion disorder date from those of

Charcot, which generally involved symptom removal by sug-gestion or hypnosis.

Breuer and Freud, using such psychoana-lytic techniques as free association and

abreaction of repressed affects, had more ambitious objectives in their

treatment of Anna O, including the resolution of unconscious conflicts. To

date, whereas some recommend long-term, intensive, insight-oriented

psychodynamic psychotherapy in pursuit of such goals, most psychiatrists

advocate a more pragmatic approach, espe-cially for acute cases.

Therapeutic approaches vary according to whether the conversion symptom

is acute or chronic. Whichever the case, di-rect confrontation is not

recommended. Such a communication may cause a patient to feel even more

isolated. An undiscovered physical illness may also underlie the presentation.

In acute cases, the most frequent initial aim is removal of the symptom.

The pressure behind accomplishing this de-pends on the distress and disability

associated with the symptom (Ford, 1995). If the patient is not in great

distress and the need to regain function is not immediate, a conservative

approach of re-assurance, relaxation and suggestion is recommended. With this

technique, the patient is reassured that on the basis of evaluation the symptom

will disappear completely and, in fact, is already be-ginning to do so. The

patient can then be encouraged to ventilate about recent events and feelings,

without any causal relationships being suggested. This is in contrast to

attempts at abreaction, by which repressed material, particularly regarding a

painful experience or a conflict, is brought back to consciousness.

If symptoms do not resolve with such conservative ap-proaches, a number

of other techniques for symptom resolu-tion may be instituted. It does

appear that prompt resolution of conversion symptoms is important because the

duration of con-version symptoms is associated with a greater risk of

recurrence and chronic disability. The other techniques include narcoanalysis

(e.g., amobarbital interview), hypnosis and behavioral therapy. In

narcoanalysis, amobarbital or another sedative–hypnotic medi-cation such as

lorazepam is given intravenously to the point of drowsiness. Sometimes this is

followed by administration of a stimulant medication, such as methamphetamine.

The patient is then encouraged to discuss stressors and conflicts. This

tech-nique may be effective acutely, leading to at least temporary symptom

relief as well as expansion of the information known about the patient. This

technique has not been shown to be especially effective with more chronic

conversion symptoms. In hypnotherapy, symptoms may be removed with the

suggestion that the symptoms will gradually improve posthypnotically.

Infor-mation regarding stressors and conflicts may be explored as well. Formal

behavioral therapy, including relaxation training and even aversive therapy,

has been proposed and reported by some to be ef-fective. In addition, simply

manipulating the environment to inter-rupt reinforcement of the conversion

symptom is recommended.

Anecdotally, somatic treatments including phenothiazines, lithium and

electroconvulsive therapy have been reported effec-tive. However, in many

cases, this may be attributable to sim-ple suggestion. In other cases,

resolution of another psychiatric disorder, such as a psychotic disorder or a

mood disorder, may have led to the symptom’s removal. It should be evident from

the preceding discussion that in acute conversion disorders, it may be not the

particular technique but the influence of suggestion that is specifically

associated with symptom relief. It is likely that in various rituals, such as

exorcism and other religious ceremonies, immediate “cures” are based on

suggestion. Suggestion seems to play a major role in the resolution of “mass

hysteria”, in which a group of individuals who believe that they have been

exposed to some noxious influence such as a “toxin” or even a “spell”

expe-rience similar symptoms that do not appear to have any organic basis.

Often, the epidemic can be contained if affected individu-als are segregated.

Simple announcements that no such factor has been identified and that symptoms

experienced by the group have been linked to mass hysteria have been effective.

Thus far, this discussion has centered on acute treatment primarily for

symptom removal. Longer-term approaches include strategies previously discussed

for somatization disorder – a pragmatic, conservative approach involving

support and explo-ration of various conflict areas, particularly of

interpersonal re-lationships. A certain degree of insight may be attained, at

least in terms of appreciating relationships between various conflicts and

stressors and the development of symptoms. Others advocate long-term,

intensive, insight-oriented dynamic psychotherapy.

Related Topics