Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Somatoform Disorders

Somatization disorder: Course, Natural History and Prognosis

Course, Natural History and Prognosis

Somatization disorder is rare in children younger than 9 years of age.

Characteristic symptoms of somatization disorder usually begin during

adolescence, and the criteria are met by the mid-twenties. Somatization

disorder is a chronic illness characterized by fluctuations in the frequency

and diversity of symptoms. Full remissions occur rarely, if ever. Whereas the

most active sympto-matic phase is in early adulthood, aging does not appear to

lead to total remission. Pribor and colleagues (1994) found that women with

somatization disorder older than 55 years did not differ from younger

somatization patients in the number of somatic symp-toms. Longitudinal

follow-up studies have confirmed that 80 to 90% of patients initially diagnosed

with somatization disorder will maintain a consistent clinical picture and be

rediagnosed similarly after 6 to 8 years. Women with somatization disorder seen

in psychiatric settings are at increased risk for attempted suicide, although

such attempts are usually unsuccessful and may reflect manipulative gestures

more than intent to die. It is not clear whether such risk is true for patients

with somatization disorder seen only in general medical settings.

Treatment

First, a “management” rather than a “curative” strategy is rec-ommended

for somatization disorder. With the current absence of an identified definitive

treatment, a modest, practical, em-pirical approach should be taken. This

should include efforts to minimize distress and functional impairments

associated with the multiple somatic complaints; to avoid unwarranted

diagnos-tic and therapeutic procedures and medications; and to prevent

potential complications including chronic invalidism and drug dependence.

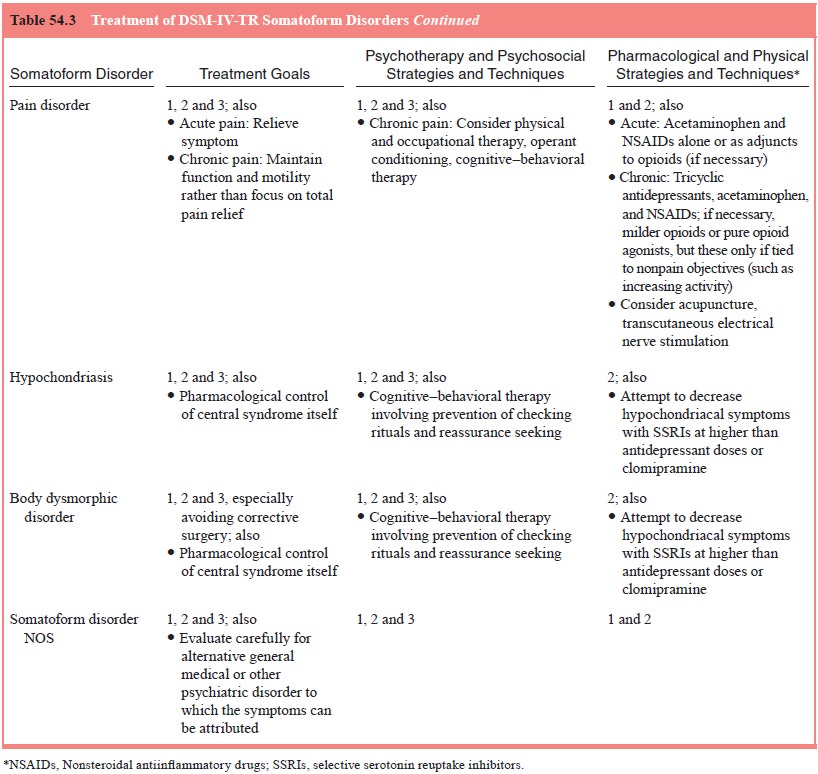

In such regard, the general recommendations outlined for somatoform

disorders should be followed (see Table 54.3). The patient should be encouraged

to see a single physician with an understanding of and, preferably, experience

in treating somatization disorder. This helps limit the number of unneces-sary

evaluations and treatments. Most clinicians advocate rou-tine, brief,

supportive office visits scheduled at regular intervals to provide reassurance

and prevent patients from “needing to develop” symptoms to obtain care and

attention. This “medical” management can well be provided by a primary care

physician, perhaps with consultation with a psychiatrist. The study by Smith

and colleagues (1986) demonstrated that such a regimen led to markedly

decreased health care costs, with no apparent decre-ments in health or

satisfaction of patients.

The foundations of treatment for this disorder are: 1) es-tablishment of

a strong physician–patient relationship or bond; 2) education of the patient

regarding the nature of the psychiatric condition; and 3) provision of support

and reassurance.

The first component, establishing a strong therapeutic bond, is

important in the treatment of somatization disorder. Without it, it will be

difficult for the patient to overcome skepti-cism deriving from past experience

with many physicians and other therapists who “never seemed to help”. In

addition, trust must be strong enough to withstand the stress of withholding

unwarranted diagnostic and therapeutic procedures that the pa-tient may feel

are indicated. The cornerstone of establishing a therapeutic relationship is

laid when the psychiatrist indicates an understanding of the patient’s pain and

suffering, legitimizing the symptoms as real. This demonstrates a willingness

to provide direct compassionate assistance. A full investigation of the

medi-cal and psychosocial histories, including extensive record review, will

illustrate to patients the willingness of the psychiatrist to gain the fullest

understanding of them and their plight. This also provides another opportunity

to evaluate for the presence of an underlying medical disorder and to obtain a

fuller picture of psychosocial difficulties that may relate temporally to

somatic symptoms.

Only after the diagnosis has been clearly established and the

therapeutic alliance is firmly in place can the psychiatrist confidently limit

diagnostic evaluations and therapies to those performed on the basis of

objective findings as opposed to merely subjective complaints. Of course, the

psychiatrist should remain aware that patients with somatization disorder are

still at risk for development of general medical illnesses so that a vigilant

per-spective should always be maintained.

The second component is education. This involves advis-ing patients that

they suffer from a “medically sanctioned ill-ness”, that is, a condition

recognized by the medical community and one about which a good deal is known.

Ultimately, it may be possible to introduce the concept of somatization

disorder, which can be described in a positive light (i.e., the patient does

not have a progressive, deteriorating, or potentially fatal medical disorder,

and the patient is not “going crazy” but has a condition by which many symptoms

will be experienced). A realistic discussion of prognosis and treatment options

can then follow.

The third component is reassurance. Patients with soma-tization disorder

often have control and insecurity issues, which often come to the forefront

when they perceive that a particular physical complaint is not being adequately

addressed. Explicit reassurance should be given that the appropriate inquiries

and investigations are being performed and that the possibility of an

underlying physical disorder as the explanation for symptoms is being

reasonably considered.

In time, it may be appropriate gradually to shift emphasis away from

somatic symptoms to consideration of personal and interpersonal issues. In some

patients, it may be appropriate toposit a causal theory between somatic

symptoms and “stress”, that is, that there may be a temporal association

between symp-toms and personal, interpersonal and even occupational prob-lems.

In patients for whom such “insight” is difficult, behavioral techniques may be

useful.

Even following such therapeutic guidelines, patients with somatization

disorder are often difficult to treat. Attention-seek-ing behavior, demands and

manipulation are common, necessi-tating firm limits and careful attention to

boundary issues. This, again, is a management rather than a curative approach.

Thus, such behaviors should generally be dealt with directively rather than

interpreted to the patient.

Pharmacological and Other Somatic Treatments

No effective somatic treatments for somatization disorder itself have

been identified.

Patients with somatization disorder may complain of anxi-ety and

depression, suggesting readily treatable comorbid psy-chiatric disorders. As

previously discussed, it is often difficult to distinguish actual comorbid

conditions from aspects of somato-form disorder itself. Pharmacological

interventions are likely to be helpful in the former but not in the latter. At

times, such discrimination will be impossible, and an empirical trial of such

treatments may be indicated. Patients with somatization disor-der are often

inconsistent and erratic in their use of medications. They will often report

unusual side effects that may not be ex-plained pharmacologically. This makes

evaluation of treatment response difficult. In addition, drug dependence and

suicide ges-tures and attempts are not uncommon.

Related Topics