Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Somatoform Disorders

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Definition

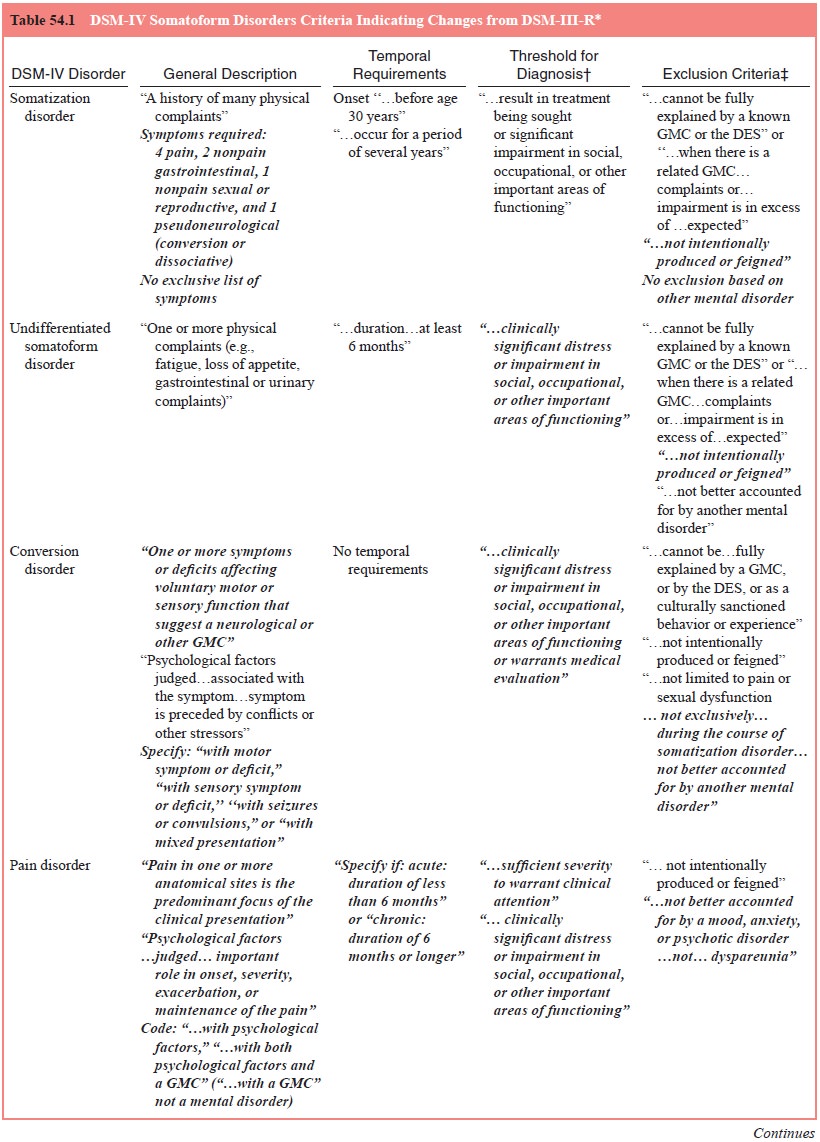

The essential feature of this disorder is preoccupation with an imagined

defect in appearance or a markedly excessive concern with a minor anomaly (see

Table 54.1). In body dysmorphic dis-order, a person could be preoccupied with

an imagined defect while she or he actually had some other anomaly and was not

normal appearing. To exclude conditions with trivial or minor symptoms, the

preoccupation must cause clinically significant distress or impairment. By

definition, body dysmorphic disorder is not diagnosed if symptoms are limited

to preoccupation with body weight, as in anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa,

or to perceived inappropriateness of sex characteristics, as in gender identity

disorder.

Preoccupations most often involve the nose, ears, face, or sexual

organs. Common complaints include a diversity of imag-ined flaws of the face or

head, including defects in the hair (e.g., too much or too little), skin (e.g.,

blemishes), and shape or sym-metry of the face or facial features (e.g., nose

is too large and deformed). However, any body part may be the focus, including

genitals, breasts, buttocks, extremities, shoulders and even over-all body

size.

Body dysmorphic disorder has been well described in the European and

Japanese literature, generally designated dys-morphophobia, often under the

rubric of the monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychoses. Until recently, it had

been virtually ignored in the US literature as well as clinically.

The definition of the disorder was reexamined for DSM-IV on several

counts, but especially as to its relationship to other psychiatric disorders

(Phillips and Hollander, 1996). After much deliberation, it was determined that

body dysmorphic disorder, although often comorbid with anxiety and mood

disorders, was sufficiently discrete to be maintained as a separate disorder.

As discussed in the differential diagnosis section, it can be distin-guished

from depressive disorders and from most anxiety dis-orders, although it

resembles obsessive–compulsive disorder in phenomenology, course and even

response to treatment. It was also decided to keep it with the somatoform

disorders grouping, although it does not share much with the other disorders in

this grouping (with the exception of hypochondriasis), beyond the fact that

affected patients are generally referred to psychiatrists from other physicians

and that they also present with medically unexplained physical complaints

(defects in appearance in body dysmorphic disorder).

As De Leon and colleagues (1989) pointed out, it is ex-tremely difficult

to determine whether a dysmorphic concern is delusional as in that with body

dysmorphic disorder, for a continuum exists from clearly nondelusional

preoccupations to unequivocal delusions such that defining a discrete boundary

between the two ends of the spectrum would be artificial. Fur-thermore,

individual patients seem to move back and forth along this continuum. Support

for rejecting the exclusion is prelimi-nary evidence that dysmorphic

preoccupations may respond to the same pharmacotherapy (SSRIs), regardless of

whether the concerns are delusional. Perhaps as a reflection of the state of

knowledge at this point, both body dysmorphic disorder and de-lusional

disorder, somatic type, can be diagnosed on the basis of the same symptoms, in

the same individual, at the same time. Thus, the definition of body dysmorphic

disorder differs from hypochondriasis, which is not diagnosed if

hypochondriacal concerns are determined to be delusional.

Epidemiology

Knowledge of such parameters is still incomplete. In general, patients

with body dysmorphic disorder first present to nonpsy-chiatrists such as

plastic surgeons, dermatologists and internists because of the nature of their

complaints and are not seen psy-chiatrically until they are referred (De Leon et al., 1989). Many resist or refuse

referral because they do not see their problem as psychiatric; thus, study of

psychiatric clinic populations may un-derestimate the prevalence of the

disorder. It has been estimated that 2% of patients seeking corrective cosmetic

surgery suffer from this disorder. Although women outnumber men in this

pop-ulation, it is not known whether this sex distribution holds true in the

general population.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

A number of sociological, psychological and neurobiological theories

have been proposed. Body dysmorphic disorder has been explained, at least in

part, as an exaggerated incorporation of societal ideals of physical perfection

and acceptance of cos-metic plastic surgery to attain such goals. A high

frequency of insecure, sensitive, obsessional, schizoid, anxious, narcissistic,

introverted and hypochondriacal personality traits in body dys-morphic patients

have been described (Phillips, 1991). Various psychodynamic mechanisms and

symbolic meanings of dysmor-phic symptoms have been suggested (Phillips, 1991),

going back to Freud’s case of the Wolfman who had dysmorphic preoccupa-tions

regarding his nose.

Some interesting neurobiological possibilities have emerged,

particularly concerning observations that hypochon-driasis, body dysmorphic

disorder and a number of other con-ditions involving compelling repetitive

thoughts or behaviors may respond preferentially to SSRIs, not to other

antidepressant drugs. An obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders grouping, the

pathological process of which is mediated by serotoninergic dysregulation, has

been suggested. As further evidence, symp-toms of body dysmorphic disorder as

well as those of obsessive– compulsive disorder may be aggravated by the

partial serotonin agonist m-chlorophenylpiperazine.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The preoccupations of body dysmorphic disorder must first be

differentiated from usual concerns with grooming and appear- ance. Attention to

appearance and grooming is universal and socially sanctioned. However,

diagnosis of body dysmorphic disorder requires that the preoccupation cause

clinically sig-nificant distress or impairment. In addition, in body

dysmor-phic disorder, concerns focus on an imaginary or exaggerated defect,

often of something, such as a small blemish, that would warrant scant attention

even if it were present. Persons with histrionic personality disorder may be

vain and excessively concerned with appearance. However, the focus in this

disor-der is on maintaining a good or even exceptional appearance, rather than

preoccupation with a defect. Such concerns are probably unrelated to body

dysmorphic disorder. In addition, by nature, the preoccupations in body

dysmorphic disorder are essentially unamenable to reassurance from friends or

fam-ily or consultation with physicians, cosmetologists, or other

professionals.

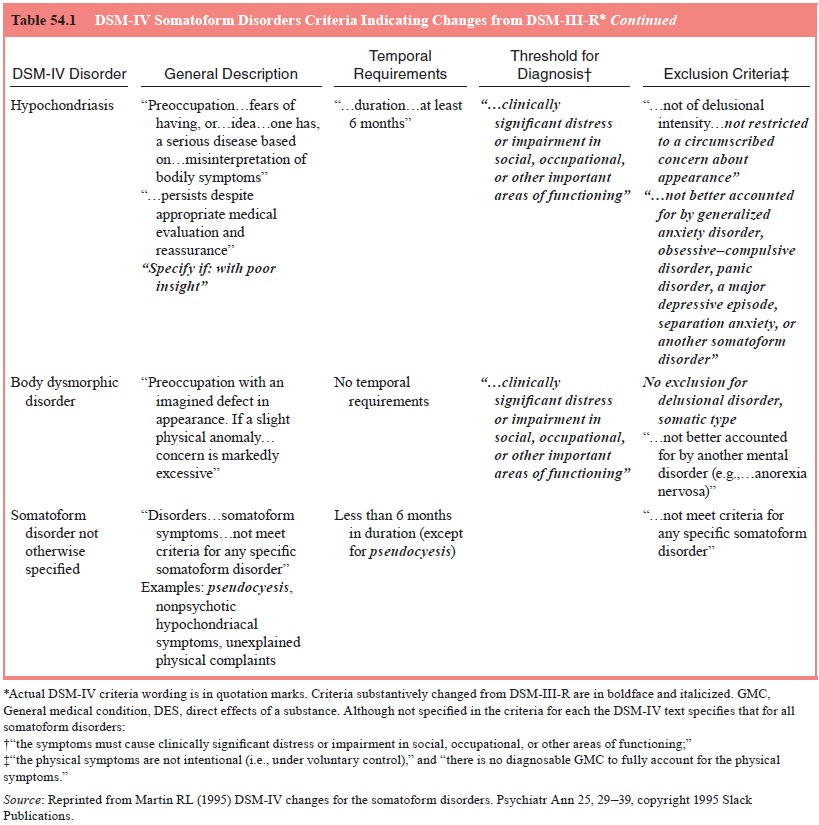

Next, the possibility of an explanation by a general medi-cal condition

must be considered (see Figure 54.1). As mentioned, patients with this disorder

often first present to plastic surgeons, oral surgeons and others, seeking

correction of defects. By the time a mental health professional is consulted,

it has generally been ascertained that there is no physical basis for the

degree of concern. As with other syndromes involving somatic preoccupa-tions

(or delusions), such as olfactory reference syndrome and delusional parasitosis

(both included under delusional disorder, somatic type), occult medical

disorders, such as an endocrine dis-turbance or a brain tumor, must be

excluded.

In terms of explanation on the basis of another psychi-atric disorder,

there is little likelihood that symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder will be

intentionally produced as in ma-lingering or factitious disorder. Unlike in

other somatoform disorders, such as pain, conversion and somatization disor-ders,

preoccupation with appearance predominates. Somatic preoccupations may occur as

part of an anxiety or mood disor-der. However, these preoccupations are

generally not the pre-dominant focus and lack the specificity of dysmorphic

symp-toms. Because patients with body dysmorphic disorder often become

isolative, social phobia may be suspected. However, in social phobia, the

person may feel self-conscious gener-ally but will not focus on a specific

imagined defect. Indeed, the two conditions may coexist, warranting both

diagnoses. Diagnostic problems may present with the mood-congruent ruminations

of major depression, which sometimes involve concern with an unattractive

appearance in association with poor self-esteem. Such preoccupations generally

lack the fo-cus on a particular body part that is seen in body dysmorphic

disorder. On the other hand, patients with body dysmorphic disorder commonly

have dysphoric affects described by them variously as anxiety or depression. In

some cases, these affects can be subsumed under body dysmorphic disorder; but

in other instances, comorbid diagnoses of anxiety or mood disorders are

warranted.

Differentiation from schizophrenia must also be made. At times, a

dysmorphic concern will seem so unusual that such a psychosis may be

considered. Furthermore, patients with this disorder may show ideas of

reference in regard to defects in their appearance, which may lead to the

consideration of schizophre-nia. However, other bizarre delusions, particularly

of persecu-tion or grandiosity, and prominent hallucinations are not seen in

body dysmorphic disorder. From the other perspective, schizo-phrenia with

somatic delusions generally lacks the focus on a particular body part and

defect. Also in schizophrenia, bizarre interpretations and explanations for

symptoms are often present, such as “this blemish was a sign from Jesus that I

am to pro-tect the world from Satan”. Other signs of schizophrenia, such as

hallucinations and disorganization of thought, are also absent in body dysmorphic

disorder. As previously mentioned, the preoc-cupations in body dysmorphic

disorder appear to be on a con-tinuum from full insight to delusional intensity

whereby the pa-tient cannot even consider the possibility that the

preoccupation is groundless. In such instances, both body dysmorphic disorder

and delusional disorder, somatic type, are to be diagnosed.

Body dysmorphic disorder is not to be diagnosed if the con-cern with

appearance is better accounted for by another psychiat-ric disorder. Anorexia nervosa,

in which there is dissatisfaction with body shape and size, is specifically

mentioned in the crite-ria as an example of such an exclusion. Although not

specifically mentioned in DSM-IV, if a preoccupation is limited to discomfort

or a sense of inappropriateness of one’s primary and secondary sex

characteristics, coupled with a strong and persistent cross-gender

identification, body dysmorphic disorder is not diagnosed.

The preoccupations of body dysmorphic disorder may resemble obsessions

and ruminations as seen in obsessive– compulsive disorder. Unlike the

obsessions of obsessive–com-pulsive disorder, the preoccupations of body

dysmorphic disor-der focus on concerns with appearance. Compulsions are limited

to checking and investigating the perceived physical defect and attempting to

obtain reassurance from others regarding it. Still, the phenomenology is

similar, and the two disorders are often comorbid. If additional obsessions and

compulsions not related to the defect are present, obsessive–compulsive

disorder can be diagnosed in addition to body dysmorphic disorder.

Course, Natural History and Prognosis

Age at onset appears to peak in adolescence or early adulthood. Body

dysmorphic disorder is generally a chronic condition, with a waxing and waning

of intensity but rarely full remission. In a lifetime, multiple preoccupations

are typical; in one study, the average was four (Phillips et al., 1993). In some, the same preoc-cupation remains unchanged.

In others, new perceived defects are added to the original ones. In others

still, symptoms remit, only to be replaced by others. The disorder is often

highly in-capacitating, with many patients showing marked impairment in social

and occupational activities. Perhaps a third becomes housebound. Most attribute

their limitations to embarrassment concerning their perceived defect, but the

attention and time-consuming nature of the preoccupations and attempts to

inves-tigate and rectify defects also contribute. The extent to which patients

with body dysmorphic disorder receive surgery or medi-cal treatments is

unknown. Superimposed depressive episodes are common, as are suicidal ideation

and suicide attempts. Actual suicide risk is unknown.

In view of the nature of the defects with which patients are preoccupied,

it is not surprising that they are found most com-monly among patients seeking

cosmetic surgery. Preoccupations persist despite reassurance that there is no

defect to correct surgi-cally. Surgery or other corrective procedures rarely if

ever lead to satisfaction and may even lead to greater distress with the

per-ception of new defects attributed to the surgery.

Treatment

First, the generic goals and treatments as outlined for the so-matoform

disorders overall should be instituted. These are beneficial in interrupting an

unending procession of repeated evaluations and the possibility of needless

surgery, which may lead to additional perceptions that surgery has resulted in

fur-ther disfigurement.

Traditional insight-oriented therapies have not generally proved to be

effective. Results with traditional behavioral tech-niques, such as systematic

desensitization and exposure therapy, have been mixed. At least without

amelioration with effective pharmacotherapy, the preoccupations do not

extinguish as would be expected with phobias. A cognitive–behavioral approach

similar to what was recommended for hypochondriasis may be more effective. This

includes response prevention techniques whereby the patient is not permitted

repetitively to check the perceived defect in mirrors. In addition, patients

are advised not to seek reassurance from family and friends, and these persons

are instructed not to respond to such inquiries. Some patients adopt such

behaviors spontaneously, avoiding mirrors and other reflecting surfaces,

refusing even to allude to their perceived de-fects to others. Such

“self-techniques” may be encouraged and refined.

Biological treatments have long been used but until re-cently were of

limited benefit to patients with body dysmorphic disorder. Approaches have

included electroconvulsive therapy, tricyclic and MAOI antidepressants, and

neuroleptics, particu-larly pimozide. In most reports of positive response to

tricyclic or MAOI antidepressant drugs, it is unclear whether response was

truly in terms of the dysmorphic syndrome or simply represented improvement in

comorbid depressive or anxiety syndromes. Re-sponse to neuroleptic treatment

has been suggested as a diagnos-tic test to distinguish body dysmorphic

disorder from delusional disorder, somatic type. The delusional syndromes often

respond to neuroleptics; body dysmorphic disorders, even when the body

preoccupations are psychotic, generally do not. Pimozide has been singled out

as a neuroleptic with specific effectiveness for somatic delusions, but this

specificity does not appear to apply to body dysmorphic disorder.

An exception to this uninspiring picture is the observa-tion of a

possible preferential response to antidepressant drugs with serotonin reuptake

blocking effects, such as clomipramine, or SSRIs, such as fluoxetine and

fluvoxamine (Hollander et al., 1992).

Phillips and coworkers (1993) reported that more than 50% of patients with body

dysmorphic disorder showed a partial or complete remission with either

clomipramine or fluoxetine, a response not predicted on the basis of coexisting

major depres-sive or obsessive–compulsive disorder. As with hypochondria-sis,

effectiveness is generally achieved at levels recommended for

obsessive–compulsive disorder rather than for depression (e.g., 60–80 mg rather

than 20–40 mg/day of fluoxetine). The SSRIs appear to ameliorate delusional as

well as nondelusional dysmorphic preoccupations. Successful augmentation of

clomi-pramine or SSRI therapy has been suggested with buspirone, another drug with

serotoninergic effects. Neuroleptics, particu-larly pimozide, may also be

helpful adjuncts, particularly if de-lusions of reference are present. Little

seems to be gained with the addition of anticonvulsants, or benzodiazepines to

the SSRI therapy.

As yet, rigorous studies have not been conducted, but anecdotal

observations and open-label studies show promise for effective treatment with

SSRIs and other serotoninergic agents for this, until now, therapeutically

exasperating disor-der. If such approaches fulfill their initial promise,

integratedapproaches using pharmacotherapy and other modalities such as

cognitive–behavioral therapy may provide effective treat-ment options.

Related Topics