Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Somatoform Disorders

Pain Disorder

Pain Disorder

Definition

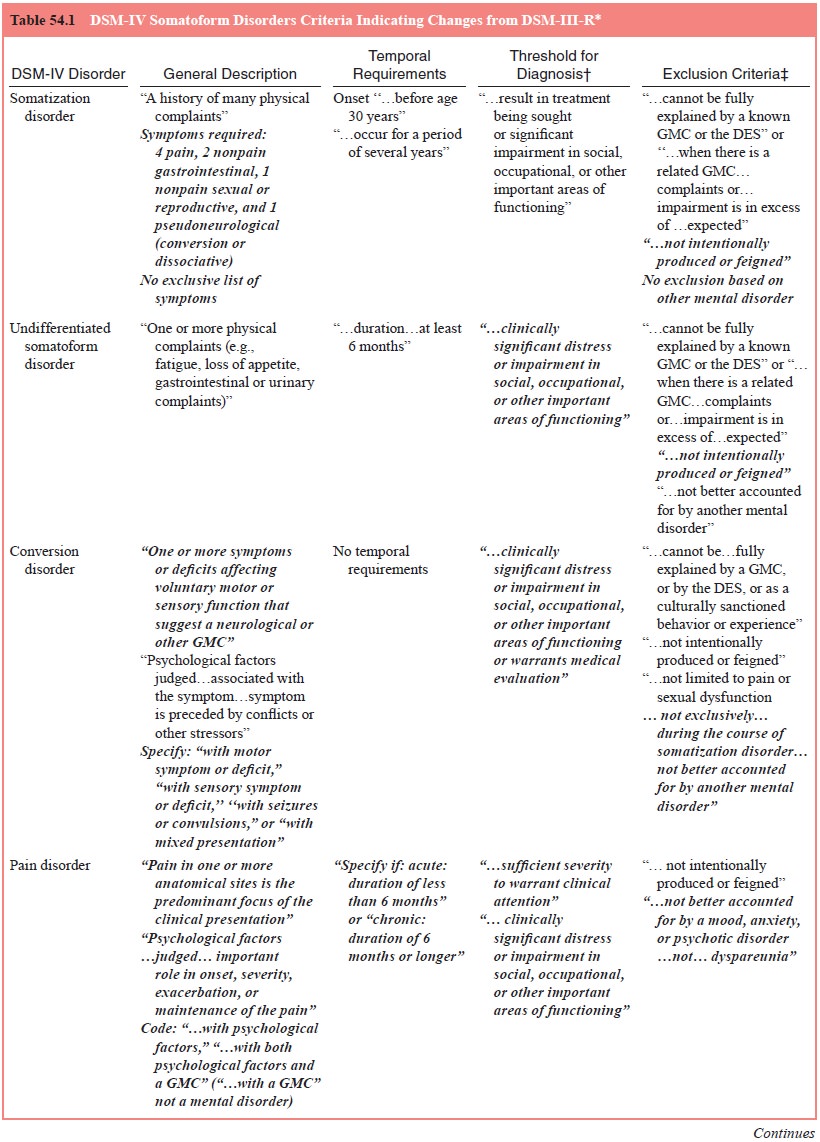

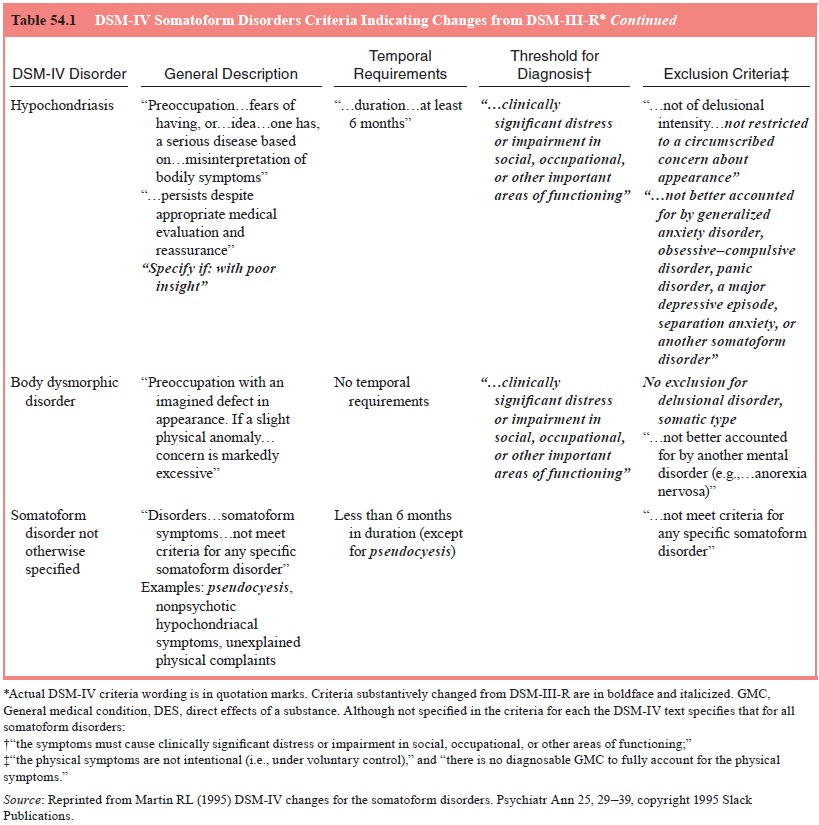

As defined in DSM-IV, the essential feature of pain disorder is pain

with which psychological factors “have an important role in the onset,

severity, exacerbation, or maintenance” (see Table 54.1). Pain disorder is

subtyped as pain disorder associated with psychological factors and pain

disorder associated with both psycho-logical factors and a general medical

condition. The third possibility, pain disorder associated with a general

medical condition, is not con-sidered to be a mental disorder, because the

requirement is not met that psychological factors play an important role. Thus,

the DSM-IV concept of pain disorder allows the psychiatrist greater specifi-city

in considering etiological factors and a more useful schema for differential

diagnosis. The focus is placed on the presence of psychological factors rather

than the exasperating determination of whether the pain is attributable to

organic disease.

In addition, DSM-IV requires that pain be the predominant focus of the

clinical presentation and that it cause clinically sig-nificant distress or

impairment. Specifiers of acute (duration of less than 6 months) and chronic

(duration of 6 months or longer) are provided.

Epidemiology

As to pain itself, some empirical studies suggest that it is com-mon.

Perhaps as indirect evidence of this is the proliferation of pain clinics

nationally. Of course, many patients attending these clinics fall into the category

of pain disorder associated with a general medical condition, but undoubtedly,

some also have in-volvement of psychological factors as required for a

diagnosis of pain disorder as a mental disorder. The same would apply to the 10

to 15% of adults in the USA in any given year who have work disability because

of back pain. Pain has been found to be a predominant symptom in 75% of

consecutive general medical patients, with 75% of these (thus 50% overall)

judged as hav-ing no identifiable physical cause. No apparent physical basis is

found in 40 to 50% of patients presenting with nonspecific ab-dominal pain. At

least half of such patients show major personal-ity problems in addition, with

such aberrations associated with poor outcome. Whereas primary care and other

nonpsychiatric physicians probably see most pain patients, 38% of psychiatric

inpatient admissions and 18% attending a psychiatric outpatient clinic report

pain as a significant problem.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

In considering the etiology of pain disorder, possible mecha-nisms of

pain itself must be considered. The definition of pain sanctioned by the

International Association for the Study of Pain Subcommittee on Taxonomy is “an

unpleasant sensory and emo-tional experience associated with actual or

potential tissue dam-age”. It goes on to acknowledge that pain is not simply

“activity induced in the nociceptor and nociceptive pathways by a noxious

stimulus” but “is always a psychological state…”. Thus, it accepts the

hypothesis that pain involves psychological as well as physi-cal factors.

Many theories of the etiology and pathophysiology of pain involving both

biological and psychological factors have been proposed. It is known that a

neuropathway descends from the cerebral cortex and medulla, which inhibits the

firing of pain transmission neurons when it is activated. This system is

appar-ently mediated by the endogenous opiate-like compounds, en-dorphins and

by serotonin. Indeed, metabolites of both of these neurotransmitters may be

reduced in the cerebrospinal fluid of chronic pain patients.

The gate

control theory links biological and psychological factors. It hypothesizes a

gate-like mechanism involving the dor-sal horn of the spinal cord by which

large A-beta fibers as well as small A-delta and C fibers carry impulses from

the periphery to the substantia gelatinosa and T-cells in the spinal cord.

Activation of the large fibers inhibits, whereas activation of the small fibers

facilitates transmission to the T-cells. In addition, impulses de-scending from

the brain, influenced by cognitive processes, may either inhibit or facilitate

transmission of pain impulses. Such a

mechanism may explain how psychological processes affect pain perception.

By definition, both pain disorder associated with psycho-logical factors

and pain disorder associated with both psychologi-cal factors and a general

medical condition involve psychological factors. In the case of the former, it

is presumed that there is little contribution from general medical conditions;

in the latter, both physical and psychological factors contribute. A plethora

of not necessarily mutually exclusive theories has been proposed to ex-plain

how this takes place.

Psychological constructs involving learning theories, both operant and

classical conditioning, may apply. In operant paradigms, pain-related

complaints are reinforced by increased attention, relief from obligations,

monetary compensation and the pleasurable effects of analgesics. In classical

conditioning, originally neutral settings such as a workplace or bedroom where

pain was experienced come to evoke pain-related behavior. So-cial and cultural

attitudes may also have effects. Patients with un-explained pain are more

likely than others to have close relatives with chronic pain. Although findings

have differed from study to study, ethnic differences may also have effects,

such as greater pain tolerance in Irish and Anglo-Saxon groups in comparison to

southern Mediterranean groups.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

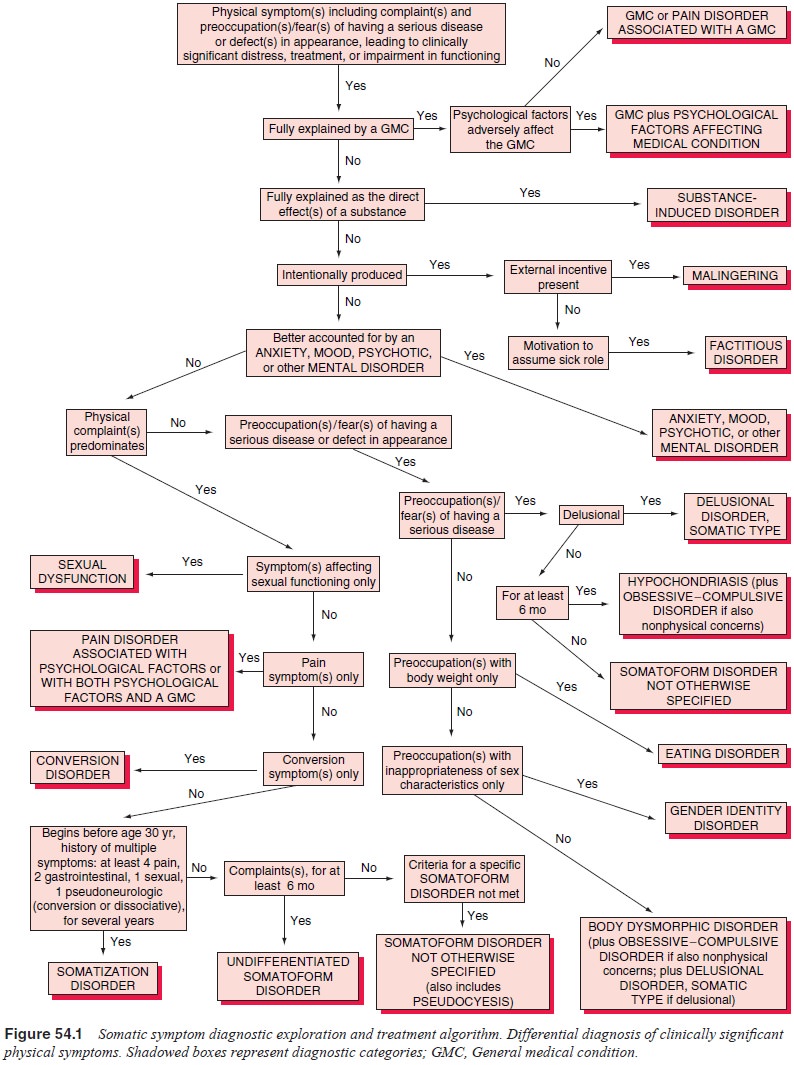

As shown in Figure 54.1, the diagnostic approach begins with assessment

of whether the presentation is fully explained by a general medical condition.

If not, it may be assumed that psycho-logical factors play a major role. If it

is judged that psychological factors do not play a major role, a diagnosis of

pain disorder asso-ciated with a general medical condition may apply. As

previously mentioned, this does not have a mental disorder code.

If psychological factors are involved, the first considera-tion is

whether the pain is feigned. If so, either malingering or factitious disorder

is diagnosed, depending on whether external incentives or assumption of the

sick role is the motivation. Evi-dence of malingering includes consideration of

external rewards relative to the chronology of the development and maintenance

of the pain. In factitious disorder, a pattern of successive hospi-talizations

and medical evaluations is evident. Inconsistency in presentation, lack of

correspondence to known anatomical path-ways or disease patterns, and lack of

associated sensory or mo-tor function changes suggest malingering or factitious

disorder, but pain disorder associated with psychological factors may show this

pattern as well. The key question is whether the patient is experiencing rather

than feigning the pain.

Determination of the relative contributions of psychologi-cal and

general medical factors is difficult. Of course, careful assessment of the

nature and severity of the potential underlying medical condition and the nature

and degree of pain that would be expected should be made. Traditionally, the

so-called conver-sion V or neurotic triad (consisting of elevation of the

hypochon-driasis and hysteria scales with a lower score on the depression

scale) on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory has been purported to

indicate emotional indifference to the somatic concerns as might be expected if

the symptom is attributable to psychological factors rather than organic

disease. However, evidence indicates that this configuration may also occur as

an adjustment to chronic illness.

A diagnosis of pain disorder requires that the pain be of sufficient

severity to warrant clinical attention, that is, it causes clinically

significant distress or impairment. A number of instruments have been developed

to assess the degree of distress associated with the pain. Such measures

include the numerical rating scale and visual analog scale as described by

Scott and Huskisson (1976), the McGill Pain Questionnaire and the West

Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory (Osterweis et al., 1987).

DSM-IV includes a number of exclusionary conventions. By definition, if

pain is restricted to pain with sexual intercourse, the sexual disorder,

dyspareunia, not pain disorder, is diagnosed. If pain occurs in the context of

a mood, anxiety, or psychotic disorder, pain disorder is diagnosed only if it

is an independent focus of clinical attention and is not better accounted for

by the other disorder, a highly subjective judgment.

If pain occurs exclusively during the course of somatiza-tion disorder,

pain disorder is not diagnosed because pain symp-toms are part of the criteria

for somatization disorder and are thereby subsumed under the more comprehensive

diagnosis. Because somatization disorder is virtually a lifelong condition,

this exclusion generally applies in someone with somatization disorder by

history. Important here is that, in addition to pain, somatization disorder

involves multiple symptoms of the gas-trointestinal system, the reproductive

system, and the central and peripheral nervous systems; whereas in pain

disorder, the focus is on pain symptoms only.

Specification of acute versus chronic pain disorder on the basis of

whether the duration is less than or greater than 6 months is an important

distinction. Whereas acute pain, in most cases, will be linked with physical

disorders, when pain remains unex-plained after 6 months, psychological factors

are often involved (Cloninger, 1993). However, the psychiatrist must remember

that a significant minority (in one study 19%) of patients with chronic pain of

no apparent physical origin will ultimately be found to have occult organic

disease (Cloninger, 1993).

In patients with unexplained pelvic pain, psychiatrists should be warned

about cavalier conclusions regarding the ab-sence of physical disease. With

laparoscopy, a high frequency of occult organic disease has been identified in

several stud-ies. Thus, laparoscopy may be indicated in patients with pelvic

pain. Electromyography may be helpful in distinguishing muscle contraction

headaches. Failure to show coronary artery spasm with provocative procedures

and failure to respond to nitroglyc-erin may be useful in distinguishing

patients with pain disorder from those in whom the pain is attributable to

coronary artery disease.

Course, Natural History and Prognosis

Given the heterogeneity of conditions subsumed under the pain disorder

rubric, course and prognosis vary widely. The subtyp-ing at 6 months is of

significance. The prognosis for total remis-sion is good for pain disorders of

less than 6 months’ duration. However, for syndromes of greater than 6 months’

duration, chronicity is common. The site of the pain may be another fac-tor.

Certain anatomically differentiated pain syndromes can be distinguished, and

each has its own characteristic pattern. These include syndromes characterized

primarily by headache, facial pain, chest pain, abdominal pain and pelvic pain.

In such syn-dromes, symptoms tend to be recurrent, with relapses occurring in

association with stress. A high rate of depression has been ob-served among

patients with unexplained facial pain. Facial pain is often alleviated by

antidepressant medication. This effect has been observed in both patients with

depressive symptoms and those without.

Other

factors affecting course and prognosis include as-sociated psychiatric illness

and external reinforcement. Employ-ment at the outset of treatment predicts

improvement. Chronicity is more likely in the presence of certain personality

diagnoses or traits, such as pronounced passivity and dependency. External

re-inforcement includes litigation involving potential financial com-pensation

or disability. Continuation of the pain disorder may prove more lucrative than

its resolution and return to work. Level of activity, which is generally

associated with improvement, is discouraged by fears of losing compensation.

Thus, although out-right malingering may be rare pain behaviors are often

reinforced and maintained. Habituation with addictive drugs is associated with

greater chronicity.

Treatment

An

overriding guideline is that the psychiatrist does not do any-thing that will

actually perpetuate and even promote “pain-re-lated behavior”. Thus, a major

goal is to encourage activity. Other guidelines include avoidance of

sedative–antianxiety drugs, ju-dicious use of analgesics on a fixed interval

schedule so as not to reinforce pain-related behaviors, avoidance of opioids

and con-sideration of alternative treatment approaches such as relaxation

therapy. Depression should be treated with appropriate antide-pressant drugs,

not sedative–antianxiety medications. The dif-ficulties in managing pain

disorder patients have resulted in the establishment of many clinics and

programs especially designed for pain. Referral to such a service may be

indicated. Interven-tion should best be provided early in the course of the

syndrome, before pain-related behaviors become entrenched. Once continu-ing

disability compensation is established, therapeutic efforts become much more

difficult.

The

preceding general guidelines apply whether or not a general medical basis for

the pain is involved. Of course, if only pain disorder associated with

psychological factors is involved, psychological management will be the mainstay.

For patients with pain associated with general medical factors (not a mental

disorder) in which psychological factors do not play a major role, efforts

should be made to prevent the development of psycho-logical problems in

response to the resulting distress, isolation and loss of function, and

iatrogenic effects such as exposure to potentially addicting drugs.

In acute

pain, the major goal is to relieve the pain. Thus, pharmacological agents

generally play a more significant role than in chronic syndromes. Whereas the

risk of developing opi-oid dependence appears to be surprisingly low (four per

12 000) among patients without a prior history of dependence, nonopioid agents

should be used whenever they can be expected to be ef-fective. As discussed for

chronic pain, these include particularly acetaminophen and the nonsteroidal

antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), of which aspirin is considered a member. Even

if an opioid analgesic is employed, these drugs should be continued as

adjuncts; often, they lessen the required dose of the opioid.

It is

with the chronic syndromes that proper management is crucial to ease distress

and prevent the development of addi-tional problems. As advised by King (1994),

the overriding goal is to maintain function, because total relief of the pain

may not be possible. Physical and occupational therapy may play a major role.

There may be resistance to the involvement of a psychia-trist as an indication

that the pain is not seen as real. Such issues must first be resolved. An attempt

should be made to ascertain the roles that psychological and general medical

factors play in the maintenance of the pain.

A large variety of psychotherapies including individual, group and

family strategies have been employed. Two techniques that warrant special

attention are operant conditioning and cog-nitive–behavioral therapy. In

operant conditioning, the pattern of reinforcement of pain behavior by

medication, attention and ex-cuse from responsibilities is to be interrupted

and reinforcement shifted to usual daily activities. To assess the role of

operant con-ditioning, it may be necessary to have patients keep a diary and to

interview family members to identify any conditioning patterns. In

cognitive–behavioral therapies, the goal is the identification and correction

of attitudes, beliefs and expectations. Biofeedback and relaxation techniques

may be used to minimize muscle ten-sion that may aggravate if not cause pain.

Hypnosis may also be used to achieve muscle relaxation and to help the patient

“dissoci-ate” from the pain.

Pharmacological intervention may also be useful in chronic syndromes.

Effort should be made to avoid opioids if possible. Agents to be tried first

include antidepressants, aceta-minophen, NSAIDs (including aspirin) and anticonvulsants

such as carbamazepine. Antidepressants seem particularly useful for neuropathic

pain, headache, facial pain, fibrositis and arthri-tis (including rheumatoid

arthritis). Analgesic action seems to be independent of antidepressant effects.

Most work has been done with the tricyclic antidepressants; other classes, such

as the monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and the selective serotonin

reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), may be effective as well. Although it was thought

that the action is mediated by serotonin-ergic effects, agents such as

desipramine with predominantly noradrenergic activity seem to be effective as

well. NSAIDs, of which aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen and piroxicam are commonly

used examples, may alleviate pain through inhibition of prostag-landin

synthesis. Unfortunately, this effect may also contribute to side effects, such

as aggravation of peptic or duodenal ulcers and interference with renal

function. For patients unable to tolerate NSAIDs, acetaminophen should be

tried.

If opioid analgesics are used, it is recommended that use be tied to

objectives such as increasing level of activity rather than simply pain

alleviation. Milder opioids, such as codeine, oxycodone and hydrocodone, should

be implemented first. The once widely used propoxyphene has less analgesic

effect than these drugs; it is not devoid of abuse potential as once thought

and is not recommended. Pure opioid agonists such as morphine, methadone and

hydromorphone should be tried next. Meperidine, also in this class, is contraindicated

for prolonged use because accumulation of the toxic metabolite, normeperidine,

a cerebral irritant, may result in anxiety, psychosis, or seizures. Meperidine

may also have a lethal interaction with MAOIs. There are no ad-vantages to

mixed opioid agonist–antagonists. The commonly used pentazocine should be

avoided because it has abuse poten-tial and psychotomimetic effects in some

patients. It remains to be seen whether newer agents (buprenorphine,

butonphanol and nalbuphine) have lower abuse potential as claimed. Above all,

psychiatrists should be judicious in the use of opioid analgesics, considering

not only their abuse potential but their large number of side effects including

constipation, nausea and vomiting, ex-cessive sedation and, in higher doses,

respiratory depression that may be fatal.

In addition to pharmacotherapy, a number of other “physi-cal” techniques

have been used, such as acupuncture and trans-cutaneous electrical nerve

stimulation. These carry little risk of adverse effects or aggravation of the

pain disorder. Other proce-dures such as trigger point injections, nerve blocks

and surgicalablation may be recommended if specifically indicated by an

un-derlying general medical disorder.

As can be seen in the preceding discussion, the man-agement of pain

disorders is not monomodal. A great number of psychological and physical

factors and interventions may be considered.

Related Topics