Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With HIV Infection and AIDS

Treatment of HIV Infection

Treatment

of HIV Infection

Protocols of how to treat HIV disease change

relatively often. Yearly a team of physicians from throughout the United States

evaluates the latest evidence and makes recommendations that are widely

disseminated, and monthly a subgroup evaluates available evidence (Panel on

Clinical Practices for Treatment of HIV In-fection [Panel], 2002). Treatment

decisions for an individual pa-tient are based on three factors: HIV RNA (viral

load); CD4 T-cell count; and the clinical condition of the patient (Panel,

2000). Treatment should be offered to all patients with the pri-mary infection

(acute HIV syndrome, as previously described). In general, treatment should be

offered to individuals with a T-cell count of less than 350 or plasma HIV RNA

levels exceeding 55,000 copies/mL (RT-PCR assay) (Panel, 2002).

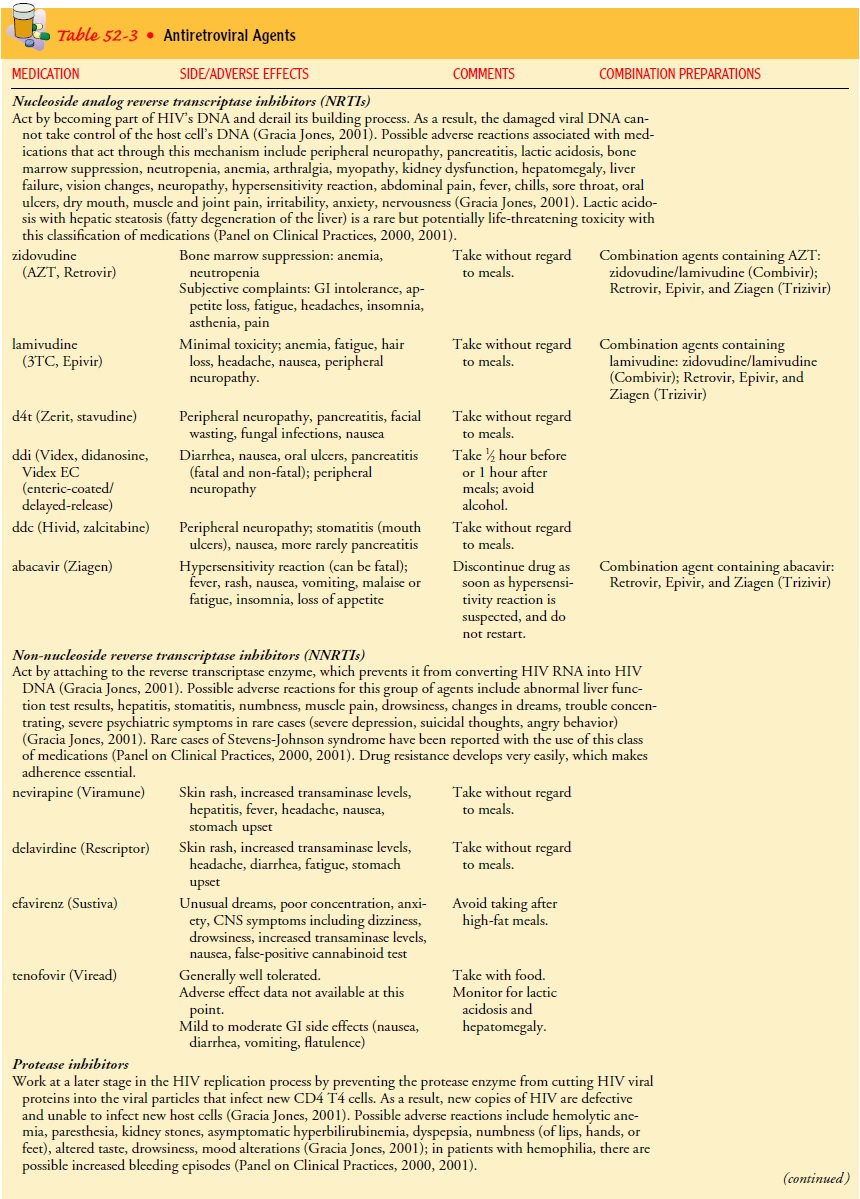

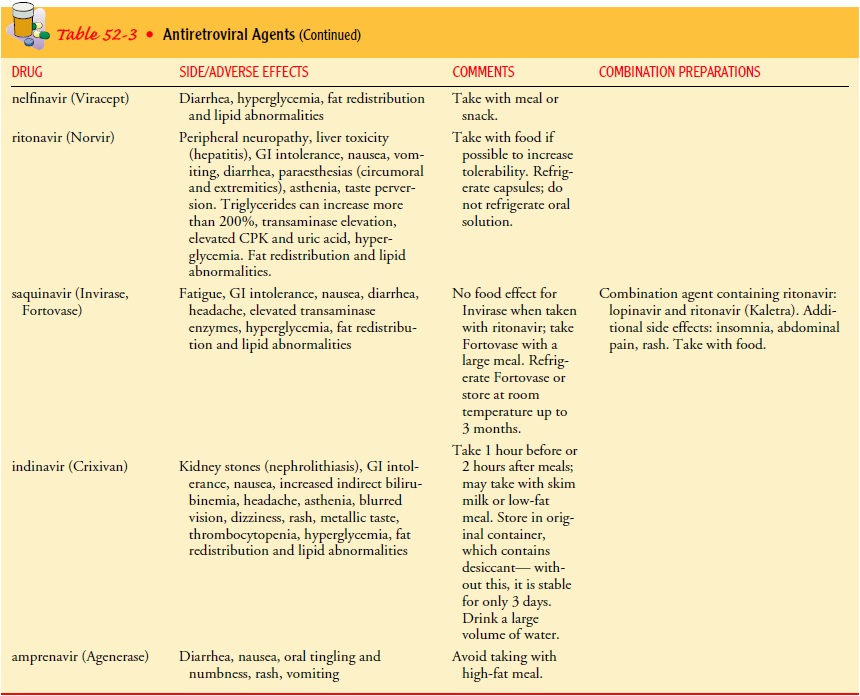

The increasing number of antiretroviral

agents (Table 52-3) and the rapid evolution of new information have introduced

ex-traordinary complexity into the treatment of HIV-infected per-sons (Panel,

2000). Adherence rates among persons living with HIV and AIDS are no different

from those of patients with other chronic diseases (Williams, 2001).

Antiretroviral regimens are complex, have major side effects, pose difficulties

with regard to adherence, and carry serious potential consequences from the

de-velopment of viral resistance due to lack of adherence to the drug regimen

or suboptimal levels of antiretroviral agents (Panel, 2000). The goals of

treatment are maximal and durable suppres-sion of viral load, restoration

and/or preservation of immunologic function, improved quality of life, and

reduction of HIV-related morbidity and mortality. The Panel’s guidelines

recommend viral load testing at diagnosis and every 3 to 4 months thereafter in

the untreated person; T-cell counts should be measured at diagnosis and

generally every 3 to 6 months thereafter.

It is

difficult to predict which patients will adhere to medica-tion regimens

(Holzemer, Corless, Nokes, et al., 1999). Perceived engagement with the health

care provider has been associated with greater adherence to HIV medication

regimens (Bakken et al., 2000). Individualized plans of care that take into

consideration housing and social support issues in addition to health indicators

are essential.

Results of therapy are evaluated with viral

load tests (Panel, 2000). Viral load levels should be measured immediately

prior to and again at 2 to 8 weeks after initiation of antiretroviral therapy,

since in most patients adherence to a regimen of potent anti-retroviral agents

should result in a large decrease in the viral load by 2 to 8 weeks. The viral

load should continue to decline over the following weeks and in most

individuals will drop below de-tectable levels (currently defined as less than

50 RNA copies/mL) by 16 to 20 weeks. The rate of viral load decline toward

unde-tectable levels is affected by the baseline T-cell count, the initial

viral load, the potency of the medication, adherence of the pa-tient to the

medication regimen, prior exposure to antiretroviral agents, and the presence

of any OIs (Panel, 2000). The confirmed absence of a viral load response should

prompt the health care team to re-evaluate the regimen.

All approved anti-HIV drugs attempt to block

viral replica-tion within cells by inhibiting either reverse transcriptase or

the HIV protease (Bartlett & Moore, 1998). A treatment duration of 5 to 7

years of continuous therapy is difficult because of the com-plexity, toxicity,

and cost of the current drug regimens, especially when the concept of

maintenance therapy with a simplified regimen does not seem viable (Ho, 1998).

Medication side effects can make life difficult and are one of the main reasons

people miss doses of the medications or stop taking them completely (Horn &

Pieribone, 1999).

All medications have toxic side effects. The

nurse can obtain Web-based information to remain current about medications used

to treat HIV/AIDS. The NIH (National Institutes of Health) maintains an AIDS

drug line Website. Increasing numbers of patients with HIV infection receiving

medications are presenting with metabolic complica-tions such as increases in

cholesterol and triglyceride levels, hyper-glycemia, and altered body habitus

(NIAID, 2001). Toxicity to cell mitochondria may be involved in many of the

side effects of HIV medications, including peripheral neuropathy, myopathy and

cardiomyopathy, lactic acidosis and hepatic steatosis (fatty degeneration of

liver), pancreatitis, osteopenia and osteoporosis, and bone marrow suppression.

Fat redistribution (lipodystrophy syndrome, also known as pseudo-Cushing’s

syndrome [Panel, 2001]) is one of the most frequent systemic side effects. Many

people who have lipodystrophy experience an increase in fat loss in the legs,

arms, and face and/or a buildup of fat around the ab-domen and at the base of

the neck. Patients may also experience an increase in breast size. These

changes in body image can be very disturbing to persons living with HIV/AIDS

and have been reported to occur in 6% to 80% of patients receiving HAART (see

following discussion). Hepatotoxicity associated with certain protease

inhibitors may limit the use of these agents, especially in patients with

underlying liver dysfunction (Panel, 2000).

Combination therapy is defined as a regimen

containing any combination of two antiretroviral agents; HAART is defined as a

regimen consisting of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase in-hibitors plus a protease inhibitor or a non-nucleoside

reverse transcriptase inhibitor, or two protease inhibitors and one other

antiretroviral agent (Agins, 2000). As new medications are devel-oped, the

number of combinations continues to increase. Safety and efficacy data on many

of the combination therapies are lim-ited. Use of three- and four-drug combination

regimens has be-come more widespread, starting earlier in the course of

infection, with careful monitoring by viral load measures. In some patients

receiving three-drug regimens, viral levels are so low that they are no longer

detectable. Future therapy may be individualized based on the viral strain and

resistance to antiretroviral drugs. Initially, HAART consisting of a

triple-drug regimen (a protease inhibitor and two non-nucleoside reverse

transcriptase inhibitors) is rec-ommended. Drawbacks of HAART are the inability

of some patients to adhere to the regimen, the need to take multiple

medications on different dosing schedules, and the risk for drug interactions.

The duration of therapy needed to control acute HIV infection is unknown, but therapy

may continue for several years or for life. Combination therapy with different

types of fusion and entry inhibitors (such as T-20) may be synergistic against

HIV. These agents fall into a new category of HIV med-ications called fusion

inhibitors and target the GP120 during the initial stage of the HIV life cycle,

which is cell fusion (Saag, 2001).

Related Topics