Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With HIV Infection and AIDS

Stages of HIV Disease

Stages

of HIV Disease

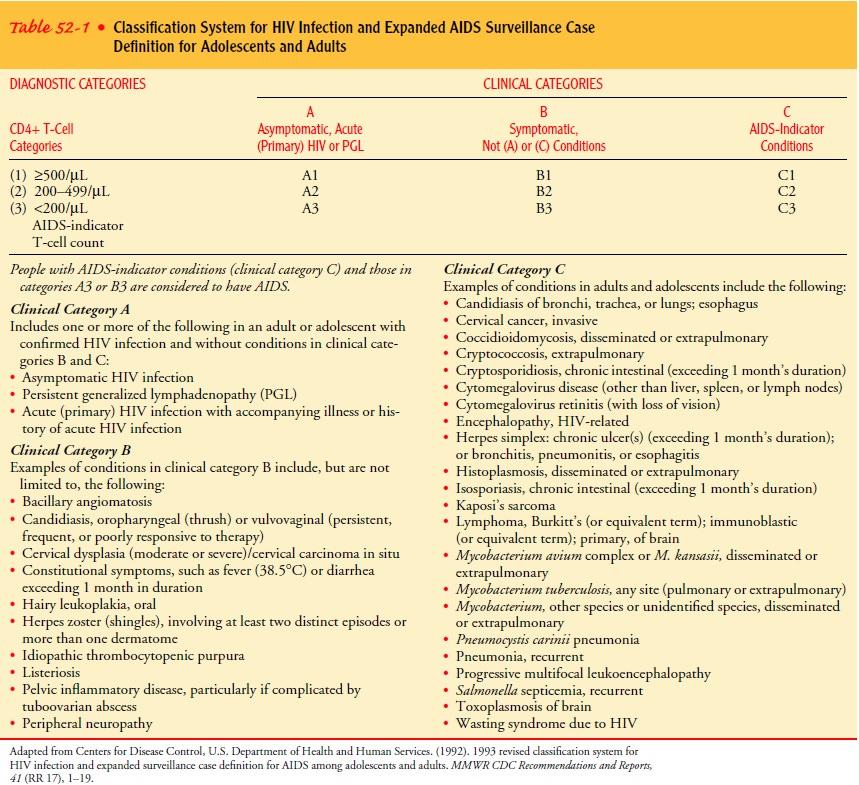

The stage of HIV disease is based on clinical

history, physical ex-amination, laboratory evidence of immune dysfunction,

signs and symptoms, and infections and malignancies. The CDC stan-dard case

definition of AIDS categorizes HIV infection and AIDS in adults and adolescents

on the basis of clinical conditions asso-ciated with HIV infection and CD4+ T-cell counts. The

classifi-cation system (Table 52-1) groups clinical conditions into one of

three categories denoted as A, B, or C.

PRIMARY INFECTION (ALSO KNOWN AS ACUTE HIV INFECTION OR ACUTE HIV SYNDROME)

The period from infection with HIV to the

development of anti-bodies to HIV is known as primary infection. During this pe-riod, there is intense viral

replication and widespread dissemination of HIV throughout the body. Symptoms

associated with theviremia range from none to severe flu-like symptoms. During

the primary infection period, the window period occurs because a person is

infected with HIV but tests negative on the HIV anti-body blood test. Although

antibodies to the HIV envelope glyco-proteins typically can be detected in the

sera of HIV-infected individuals by 2 to 3 weeks after infection, most of these

anti-bodies lack the ability to inhibit virus infection. By the time

neu-tralizing antibodies are detected, HIV-1 is firmly established in the host

(Wyatt & Sodroski, 1998). During this period, there are high levels of

viral replication and the killing of CD4 T cells, re-sulting in high levels of

HIV in the blood and a dramatic drop in CD4 T cell counts from the normal level

of at least 800 cells/mm3 of blood. About 3 weeks into this acute phase, individuals may display

symptoms reminiscent of mononucleosis, such as fever, enlarged lymph nodes, rash,

muscle aches, and headaches. These symptoms resolve within another 1 to 3 weeks

as the immune sys-tem begins to gain some control over the virus. That is, the

CD4 T-cell population responds in ways that spur other immune cells, such as

CD8 lymphocytes, to increase their killing of infected, virus-producing cells.

The body produces antibody molecules in an effort to contain the virus; they

bind to free HIV particles (outside cells) and assist in their removal

(Bartlett & Moore, 1998). This balance between the amount of HIV in the

body and the immune response is referred to as the viral set point and re-sults in a steady state of infection. During

this steady state, which can last for years, the amount of virus in circulation

and the num-ber of infected cells equal the rate of viral clearance (Ropka

& Williams, 1998).

Primary HIV infection, the time during which

the viral burden set point is achieved, includes the acute symptomatic and

early in-fection phases. During this initial stage, viral replication is

asso-ciated with dissemination in lymphoid tissue and a distinct immunologic

response. The final level of the viral set point is in-versely correlated with

disease prognosis; that is, the higher the viral set point, the poorer the

prognosis (Cates, Chesney & Cohen, 1997). The primary infection stage is

part of CDC category A.

HIV ASYMPTOMATIC (CDC CATEGORY A:MORE

THAN 500 CD4+ T LYMPHOCYTES/MM3)

On

reaching a viral set point, a chronic, clinically asymptomatic state begins.

Despite its best efforts, the immune system rarely if ever fully eliminates the

virus. By about 6 months, the rate of viral replication reaches a lower but

relatively steady state that is re-flected in the maintenance of viral levels

at a kind of “set point.” This set point varies greatly from patient to patient

and dictates the subsequent rate of disease progression; on average, 8 to 10

years pass before a major HIV-related complication develops. In this prolonged,

chronic stage, patients feel well and show few if any symptoms (Bartlett &

Moore, 1998). Apparent good health con-tinues because CD4 T-cell levels remain

high enough to preserve defensive responses to other pathogens.

HIV SYMPTOMATIC (CDC CATEGORY B: 200

TO 499 CD4+ T LYMPHOCYTES/MM3)

Over time, the number of CD4 T cells gradually falls. Category B consists of symptomatic conditions in HIV-infected patients that are not included in the conditions listed in category C. These conditions must also meet one of the following criteria: (1) the condition is due to HIV infection or a defect in cellular immu-nity, or (2) the condition must be considered to have a clinical course or require management that is complicated by HIV infec-tion. If an individual was once treated for a category B condition and has not developed a category C disease but is now symptom-free, that person’s illness would be considered category B

AIDS (CDC CATEGORY C: LESS THAN 200

CD4+ T LYMPHOCYTES/MM3)

When CD4 T-cell levels drop below 200

cells/mm3

of blood, pa-tients are said to have AIDS. As levels fall below 100, the immune

system is significantly impaired (Bartlett & Moore, 1998). Once a patient

has had a category C condition, he or she remains in cat-egory C. This

classification has implications for entitlements (ie, disability benefits,

housing, and food stamps) since these pro-grams are often linked to an AIDS

diagnosis. Although the re-vised classification emphasizes CD4+ T-cell counts, it

allows for CD4+ percentages (percentage of CD4+ T cells of total lympho-cytes). The CD4+ percentage is less

subject to variation on re-peated measurements than is the absolute CD4+ T-cell count. Less than

14% of the CD4+ T cells of the total lymphocytes is consistent with an AIDS diagnosis.

The percentage, as compared to the absolute number of CD4+ T cells, becomes

particularly important when the patient has a heightened immune response to

infections in addition to HIV. One complication of advanced HIV infection is anemia,

which may be caused by HIV, oppor-tunistic diseases, and medications (Collier

et al., 2001).

Related Topics